"I am beginning to despair

And can see only two choices:

Either go crazy or turn holy."

—Adélia Prado, “Serenade”

Sometimes the mystery of existence—that we exist at all, that we feel so homelessly at home in this place—gets embedded so deeply in life that we no longer feel it as mystery. Language, too, partakes of this sterilizing sameness and becomes in fact as solid and practical as a piece of wood or a pair of pliers, something we use during the course of interchangeable days. Poetry can reignite these dormancies (“words are fossil poetry,” as Emerson put it) of both language and life, sending a charge through reality that makes it real again.

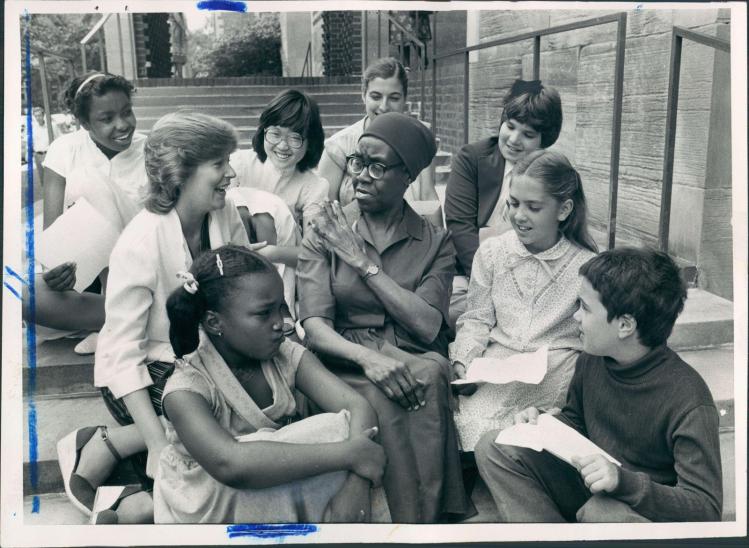

I woke this morning so leaden I could hardly rouse myself from bed. I clutched for despair, but all the loyal life buoys—failure, self-contempt, God’s “absence”—drifted out of reach. I felt...nothing, my whole being as solid and insentient as a piece of wood or a pair of pliers. (Hölderlin, going mad: “Nothing is happening to me, nothing is happening to me!”) It was a teaching day, as unluck would have it: Gwendolyn Brooks, in a graduate divinity-school seminar called “Poetry and Faith.” When I was a child, the two most intolerable aspects of my life (or the two of which I was then conscious) were church and school. Both seemed to me so geologically dull I felt my arteries hardening. It seems either cold fate or high irony, then, that I should end up in church school. Some people can’t conceive of a god who can’t suffer. Me, I can’t conceive of a god who can’t laugh.

One wants a Teller in a time like this.

One’s not a man, one’s not a woman grown

To bear enormous business all alone.

One cannot walk this winding street with pride,

Straight-shouldered, tranquil-eyed,

Knowing one knows for sure the way back home.

One wonders if one has a home.

One is not certain if or why or how.

One wants a Teller now:—

Put on your rubbers and you won’t catch cold.

Here’s hell, there’s heaven. Go to Sunday School.

Be patient, time brings all good things—(and cool

Strong balm to calm the burning at the brain?)—

Behold, Love’s true, and triumphs, and God’s actual.

—Gwendolyn Brooks, from “The Womanhood”

When first reading this poem, one is likely to understand “teller” as some sort of recorder or attentive onlooker. One wants a sensitive witness to capture and memorialize the “truth” of what happens “in a time like this.” (The surrounding poems suggest war and social crisis, but specificity isn’t needed; everyone alive has “a time like this.”) But that reading quickly collapses. (That it was possible, though, lingers through and influences the rest of the poem.) What one wants, actually, is a teller to tell one what one knows is not true. Because in fact you are going to catch cold, bone cold, and hell and heaven are hopelessly fused in this life, and time is ticking every instant toward a catastrophe orchestrated just for you.

But what about that last line? Is it merely a continuation of the wry irony of the first three lines of the stanza? Or does the parenthetical question, and the “cool strong balm” of its sound, chasten and change the tone so that the “Behold” is credibly prophetic and annunciatory, not merely mockingly so? And if that word is credible and volatile in the ancient sense, then what of the assertions that follow?

“Actual” is a very precise word, a “telling” word, a crucial wingbeat away from the word “real,” which one might have expected. “Actual” comes to us from the Old French actuel, meaning “active, practical.” Farther back, the Latin actus meant “driving, doing, act or deed” (an actus was, literally, a cattle drive). Clearly the word once referred less to a condition than an action, less to a state of being than being itself. To say that God is actual, then, in the context of this poem, is not necessarily to say that God is “real.” It’s to say that God is so woven into reality that the question of God’s own reality can’t meaningfully occur.

One more pinhole precision: “and cool / Strong balm to calm the burning at the brain.” At, not the more expected in. The burning is not psychological, or at least not entirely so, but circumstantial. The threat of meaninglessness is inside the speaker’s mind, but it is a response to a threat that is external and palpable. The powers invoked by the poem—of telling (poetry), of love and God and patience—are not simply effective in the “real” world. They are what makes the world real. In the end, this is not a poem about the reality of love, divinity, or poetry, but about the love, divinity, and poetry of reality.

Too much interpretation? Yes and no. Gwendolyn Brooks certainly never sat down and self-consciously seeded her poem with these meanings. My guess is she chose both “actual” and “at” entirely for the sounds (both of which are less predictable, less mellifluous). But that’s the mystery of language, and of its reach into—rather, its co-extensiveness with—life, love, and God. A reader’s need can release a meaning an author never intended, but which her whole-souled submission to sound enabled. That’s what happened for me in the midst of my barren dread this morning, and for the rest of the day love was true (from Old English, meaning steadfast, loyal), God was a verb (how lively and lovely the class!), and I was rescued by a revelation so tiny it would take a crazy and holy attention to see it as such.