Over the past month or so, I’ve spent many hours in emergency rooms and biding my time around hospital beds. (I’m happy to report that things have greatly improved for the patient, thank goodness.) During those idle, anxious hours, I wanted something to read that was not too distracting but was guaranteed to bring pleasure, even laughter. I immediately reached for my tattered copy of The Good Word & Other Words, a 1978 collection of essays and reviews by Wilfrid Sheed. I had read the book through a couple of times over the decades but hadn’t picked it up in a while.

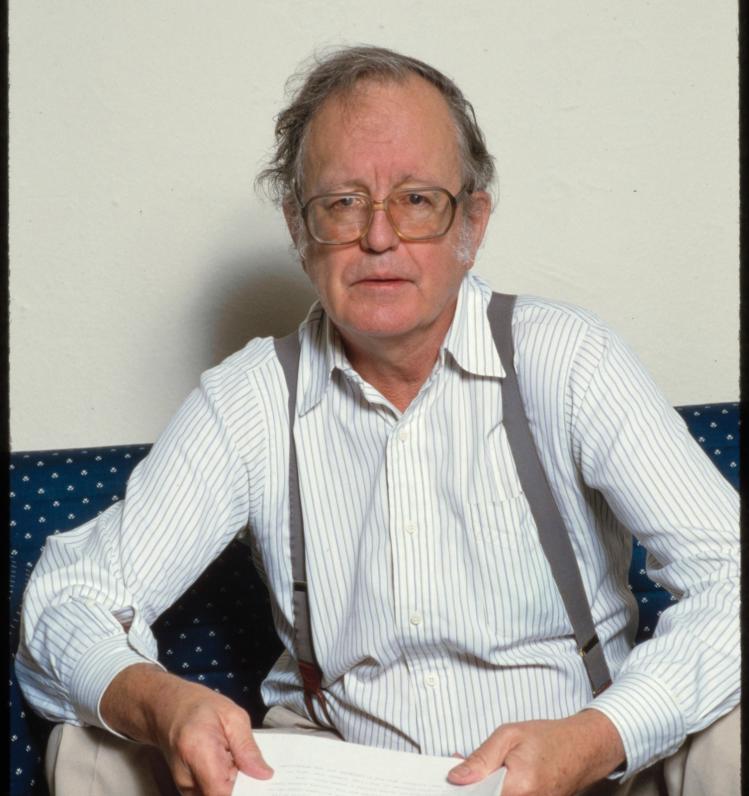

Sheed (1930–2011) was a widely respected novelist and critic, who wrote regularly for the New York Times Book Review in the 1970s and just about everywhere else over his long career. Several of his novels were nominated for the National Book Award, and he was briefly the book-review editor of Commonweal in the 1960s. Before that, he was an editor at Jubilee, the celebrated Catholic art magazine founded by Edward Rice and the poet Robert Lax in the 1950s. Sheed’s novel Office Politics is based to some degree on his time at Jubilee and Commonweal. He was born in England but moved to the United States in the 1940s. His mother, Maisie Ward, the biographer of G. K. Chesterton, and his father, the lay Catholic theologian Frank Sheed, were founders of the Catholic publishing house Sheed and Ward. Chesterton was Wilfrid Sheed’s godfather. Quite a pedigree.

What I love about Sheed’s writing is his genial wit and shrewd literary, cultural, and political assessments. The only complaint one might have is that he packs so much verbal agility and fun into nearly every sentence that it can become distracting. That said, it is hard to read any short essay of his without experiencing a rare kind of euphoria—a sense that he is determined to give the reader as much amusement as he had writing the piece.

Allow me to provide some examples. Writing about his parents’ improvisational temperament, “ideal” for running a financially precarious Catholic publishing house, he notes, “It meant not only that they could get books out of Dorothy Day as well as Monsignor Fruitcake, it also meant simple survival.” On Time publisher Henry Luce and the Cold War: “Luce in particular understood that the other great modern power blocs were animated by ideology and he reached for the only one America has in bulk, Christianity—unsuitable for war making, but people never stop trying.” According to Sheed, the Catholicism of Thomas More, the protagonist of Walker Percy’s novel Love in the Ruins, “is pagan, carnal, incarnate; he espoused it to ‘get away from the world of the spirits.’ But loving the body and keeping your hands off it is a problem to tax the keenest neo-Thomist.”

Sheed found that movie critics—and he occasionally was one—pretended to an intellectual consistency they rarely practiced. National Review’s John Simon “talks a big game about Art but he is first and foremost an unrelenting and unforgiving moralist. And yet even that line can be crossed. He rather liked Easy Rider, the summa of self-pity.”

Of poet Allen Ginsberg and the Beat Generation, Sheed shrewdly observes, “Beat euphoria fit beautifully into the spiel of the postwar pitchman. Howl, for all its originality, has some of the cadence of advertising slogans. And such Ginsbergian combos as ‘hydrogen juke box’ or ‘skin of machinery’ are just what copywriters still grope for through the Westport night.”

On Irish writers—and the Irish more generally—Sheed takes exception to one prevalent stereotype. “I have a good deal of Irish blood myself and could use some more, but also some Scotch and English, and on behalf of these two-thirds, I was outraged by a recent incident on the Dick Cavett Show. Sir Laurence Olivier had just confessed to a weakness for the grape and Cavett asked him if he was Irish. I understand the mistake, since the man is a fine actor and his name begins with an O: but it remains a heavy insult to English drinking, which is among the world’s finest, not to mention Scottish, which, despite a patron saint named Andrew, is unlike any drinking I have ever seen anywhere.”

Sheed was keen on keeping the personal allegiances and private lives of writers separate from their work.

I question the wisdom of writers coming all the way out of the closet—any closet. Having been recently accused of closet Christianity myself, I speak with feeling about closets. Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh stuck their heads briefly out of the Christian one and had to fight their way back in. Because, in an instant, the scavengers had their number—they were Catholic novelists, which explained everything: every plot twist, every two-bit apercu. The uncreative are grateful for these skeleton keys. Originality is promptly flattened like tinfoil. Catholic novelist, Catholic woman novelist; the more words you can pile up front, the less remains to be done…. G. K. Chesterton has barely recovered yet from the stuffing and mounting the Catholics gave him.

Sheed was also skeptical of writers becoming the face of any political movement. “Preaching is easier than writing, easier than thinking. I recently saw the talented reporter Gloria Steinem shilling for women’s lib (a cause I generally favor) on TV and I thought, you used to work harder than this on your articles and do more for truth and justice besides. In a world where good writers are always in much shorter supply than pontificating windbags, I hate to see even one of them mounting the pulpit in any cause whatsoever.”

Sheed somehow kept his delicate balance in the opening of a review of a book on a very delicate subject: “Books about suicide make lousy gifts, and many people think it’s unlucky to have them around the house as well: so A. Alvarez’s excellent The Savage God may wind up being more talked about than bought. A pity, because the book is also about life, just as suicide itself is about life, being in fact the sincerest form of criticism life gets.”

I could go on, but hope I’ve provided some evidence of why rereading Sheed provided me with some much-needed distraction as well as pleasure. When he graciously agreed to write a piece for Commonweal’s seventy-fifth anniversary issue, I was astonished to learn that he did not type but wrote everything out in longhand. Typing his essay into the computer was an unexpected delight.