In 1961, I started my one and only year at Saint Joseph’s Dunwoodie, the New York archdiocesan seminary. The monastic regimen and set course of studies were pretty much the same in that year as they had been in 1951, or 1941, or…. We knew, of course, that the Church’s first ecumenical council in over ninety years would open in October 1962. But it promised to be a short affair. Or so we supposed.

One person thought differently—not a faculty member, but a student in his third year of theology. Philip Murnion already showed the striking intelligence and enterprise which would make him so significant a figure in the U.S. Church for forty years, before his much-too-early death. Phil rounded up a group of eight students from different years and wrangled the required permission to meet once a week. During the compulsory daily “rec period,” he led us through the works of contemporary European theologians. And so we came to know F. X. Durrwell’s The Resurrection, Gustave Thils’s Christian Holiness, and Louis Bouyer’s Liturgical Piety. We found Bouyer particularly appealing, perhaps because the subject of liturgy was dear to us, or perhaps because we knew him to be a personal friend of the one outstanding faculty member at Dunwoodie in those days: the scripture scholar Msgr. Myles Bourke.

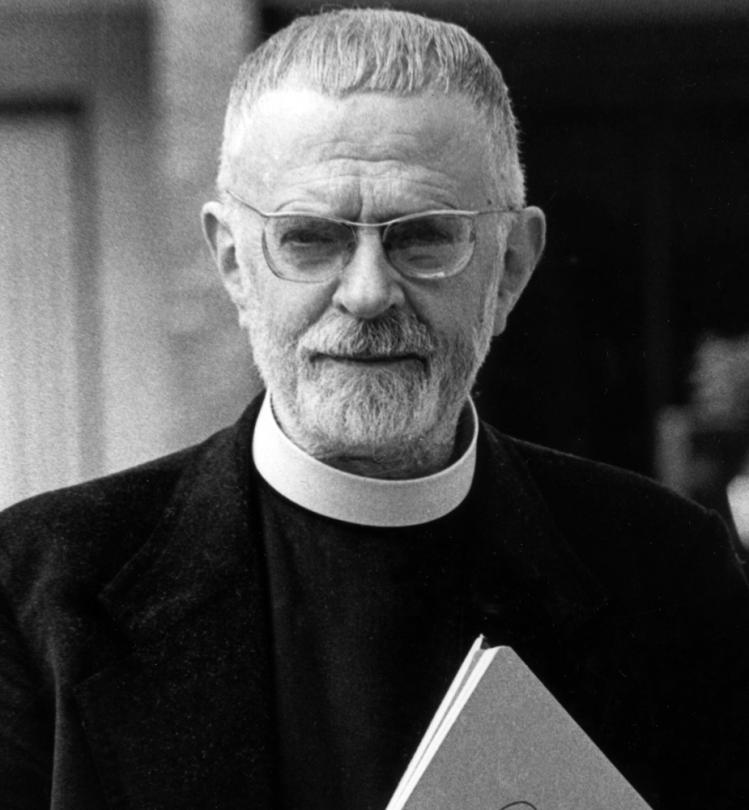

By 1961, Bouyer’s scholarly achievement was already considerable, and over the next thirty-five years he continued to produce works of theological genius. Of the great Catholic theologians of the twentieth century, he is perhaps the least known, yet he arguably has the most to contribute to our ecclesial and theological challenges today. Happily, the fine efforts of younger American theologians like Keith Lemna of the St. Meinrad School of Theology and Msgr. Michael Heintz of Mount St. Mary’s Seminary are introducing Bouyer to a new generation and rekindling the attention of people my own age.

Louis Bouyer was born in 1913, on the eve of the war whose material and spiritual devastation would forever change “Christian” Europe. Still, his childhood was relatively serene, enfolded in the warmth and faith of a loving French Protestant family. In his later years, Bouyer remembered being kissed by the then-eighty-year-old Sarah Bernhardt when he was a child. Her voice, he recalled, had “an unreal richness and sweetness,” as she whispered to him, “mon amour.”

In his childhood, Bouyer loved to read fiction and poetry, a passion that would eventually lead to four pseudonymous novels and friendship with T. S. Eliot and J.R.R. Tolkien. He was also fascinated by the natural sciences—chemistry and physics in particular. But this period of serenity and intellectual discovery came to an abrupt end when his mother died. He was only eleven. As he wrote seventy years later in his Memoirs, “With her gone, I remained totally, absolutely alone in a world emptied of any presence besides my own.” Bouyer’s father, heeding the counsel of a psychiatrist friend, arranged for the boy to spend some months with friends of his mother in the Loire River town of Sancerre. Its distinctive atmosphere provided healing balm for the youngster’s spirit. “That region will always remain something like the native land of my mind, of my soul, of my heart; in a word, of all the best that life had providentially allowed me not only to achieve, but also, I think, to be.”

It was also through people Bouyer encountered in Sancerre that he first came to read the Fathers of the Church and John Henry Newman, who would so decisively influence his future journey. He resonated deeply with Newman’s vision that “this world, wherein the intelligible and the sensible form a single tapestry, is but a single thought of God.” Bouyer had already begun to perceive and savor a sacramental universe. Within a few years he would enter the Protestant seminary in Paris and plunge into the rich liturgical and ecumenical climate of the 1930s.

During that decade Bouyer formed close ties with two men who, along with Newman, played significant roles in his emerging spiritual and theological vision: the Russian Orthodox theologian Sergei Bulgakov and the Benedictine liturgist Lambert Beauduin. Of Bulgakov’s “brilliant personality” Bouyer writes: “I straightaway had the impression of seeing reappear before me the very Christianity of the Fathers, especially the Greek Fathers.” Bulgakov strengthened Bouyer’s belief in the inseparable connection between theology and spirituality. In addition, Bouyer came to share the Russian’s conviction that “created Wisdom, which is inseparable from the uncreated Wisdom that is the Word Himself, can alone express the eternal vocation of the created universe.” As for Beauduin, Bouyer would later describe him “one of the twentieth century’s greatest religious figures because of his broad and generally correct views, be they in theology, in monasticism, in liturgy…or in ecumenism.”

It was this very commitment to liturgy and ecumenism that would lead Bouyer to convert to Catholicism in 1939 and to be ordained in 1944 as a priest of the Oratory, the congregation founded by St. Philip Neri and chosen by John Henry Newman as his own religious family. Ever ready to discern the ironies within God’s designs, Bouyer commented ruefully that, before the Second Vatican Council, his fellow Catholics often viewed him with suspicion because he was a former Protestant, while after the Council he was deemed an embarrassment precisely because he had left Protestantism to become Catholic.

During the 1950s and ’60s, Bouyer began a long and productive period of teaching in the United States: at the University of Notre Dame, the University of San Francisco, Mount St. Mary’s Seminary, and Brown University. Several of his books were actually written in English: Liturgical Piety; The Liturgy Revived: A Doctrinal Commentary of the Conciliar Constitution on the Liturgy; Liturgy and Architecture; and Newman’s Vision of Faith: A Theology for Times of General Apostasy.

Today, Bouyer may be best remembered for his involvement with Vatican II and its aftermath. During the Council itself, he was a member of the Preparatory Commission for Studies and Seminaries, an experience that soured him on “conciliarity.” He was only grateful that “the inept or incoherent proposals” that issued from the “interminable palavers” never made their way to the floor of the Council. He was, more famously, also a member of the post-conciliar Consilium for the Implementation of the Constitution on the Liturgy.

Without question, Bouyer was a firm supporter of liturgical revival. He had been involved for thirty years in the liturgical movement and had written several significant works on the meaning of the liturgy. Indeed, not only did he welcome Sacrosanctum concilium, the Council’s Constitution on the Liturgy, but his own writings, especially the groundbreaking Le Mystère Pascal (1945), undoubtedly helped shape it.

Nevertheless, he was alarmed at the haste with which the task of reform was undertaken—the effort to “recast from top to bottom and in a few months an entire liturgy it had taken twenty centuries to develop.” He also believed that the all-powerful secretary of the Consilium, Annibale Bugnini, was a man “as bereft of culture as he was of basic honesty.” Bouyer eventually discovered that Bugnini had misled both Pope Paul VI and the other members of the Consilium, in effect manipulating one against another.

A much-repeated anecdote is worth recalling. Bouyer and another member of the Consilium were charged with producing one of the new Eucharistic Prayers—by the next day. What became Eucharistic Prayer II was “cobbled together” in a café in Trastevere. Yet, despite his many misgivings about the fruits of this precipitous process, Bouyer acknowledged that there were positive accomplishments as well. He singled out “the restoration of a good number of splendid ‘Prefaces’ taken from ancient sacramentaries” and “the wider biblical readings.” Even the often-criticized new Eucharistic Prayers “reclaimed pieces of great antiquity and unequalled theological and euchological richness.”

The haste was driven in part by the convulsions that rocked both Church and society in the late 1960s. There was a sense in Rome that boundaries had to be drawn quickly, before liturgical experiments got truly out of hand. I can testify to that frenzy for change since, as a young priest, I lived at St. Thomas More House, the Catholic chaplaincy at Yale, from 1967 to 1969. Each week, a newly formed “liturgical committee” devised ever-more “relevant” celebrations, cutting and pasting with little knowledge of, or regard for, the principles set forth in Sacrosanctum concilium. The one point of reference was the ill-defined principle of “active participation,” which soon became a slogan devoid of meaning.

Bouyer’s dismay at the post-conciliar situation in France spurred him, in 1968, to write one of his most polemical books, The Decomposition of Catholicism. Here he took aim at both “integralists” and “progressives” for their failure to fathom the true meaning and depth of the reform envisaged by the Council. Both sides, Bouyer argued, domesticated the Christian Mystery. “How can the integralists,” he asked, “who turn their back to the world, ever be missionaries? And how can the progressivists, who are open to the world, but who are unaware of having anything to bring to it, be anything more?” Nor did he spare the French bishops. Commenting on some recent episcopal appointments, Bouyer echoed the view of an African bishop: “We have made generals overnight out of people chosen and trained to be nothing more than master-sergeants!” These “generals” later returned the favor: Pope Paul VI finally decided against elevating Bouyer to the cardinalate after being warned that the reaction among the episcopate in France would be intensely negative.

But what is the true depth of the Catholic liturgical tradition? That question leads to the heart of Bouyer’s liturgical-spiritual-theological vision. In the introduction to his path-breaking work of 1945, The Paschal Mystery, Bouyer signaled the trajectory of all his subsequent reflections:

The Christian religion is not simply a doctrine: it is a fact, an action, and an action, not of the past, but of the present, where the past is recovered, and the future draws near. Thus, it embodies “the mystery of faith,” for it declares to us that each day makes our own the action of Another accomplished long ago, the fruits of which we shall see only later in ourselves.

“[T]he action of Another” was, of course, the action of Jesus Christ fully revealed in his Paschal Mystery. And the entirety of the Christian life is progressively to make our own—to realize in ourselves—the fruit of that mystery. In the phrase of St. Paul that became almost the leitmotif of Bouyer’s writings on the spiritual life: “The mystery is this: Christ in you the hope of glory” (Colossians 1:27).

All of Bouyer’s theology is an exploration of the Paschal Mystery of Jesus Christ, whom we encounter in a privileged way in liturgical celebration. Bouyer’s theology is therefore inseparably liturgical-spiritual-pastoral in the tradition of the Fathers of the Church. The French philosopher of religion Jean-Luc Marion has even claimed that “the theology of Bouyer has a breadth, a spaciousness, and a breath that few others have had since the great patristic period.”

Let’s pause for a moment over the title and context of Bouyer’s seminal work, The Paschal Mystery: Meditations on the Last Three Days of Holy Week. The term “Paschal Mystery” was not in common use in the Church in the first half of the twentieth century. Indeed, Pius XII’s 1947 encyclical on the liturgy, Mediator Dei, does not use the term at all. Yet, in less than twenty years, “Paschal Mystery” would become central to Vatican II’s Constitution on the Liturgy. It is also the organizing principle for Part Two of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, promulgated in 1995.

Bouyer’s Meditations on the Last Three Days of Holy Week are all the more remarkable in that they preceded by ten years the actual reform of the Triduum undertaken by Pius XII. When Bouyer was writing this book, the solemn Easter Vigil was still celebrated early Holy Saturday morning, with sparse attendance, and—at least in my South Bronx parish—the Lord’s Resurrection was joyfully proclaimed at noon on Holy Saturday. The result was a severely truncated Triduum. Thus, Bouyer clearly anticipated and fostered the liturgical reforms that were to come.

In his fine introduction to the recent reprint of The Paschal Mystery, Michael Heintz suggests that the book presents “a lectio divina…on the texts and rites by which the Church expresses, celebrates, experiences, and communicates God’s saving work in Christ.” Note the word “experiences.” Bouyer, like his mentor Newman, is not satisfied with a merely “notional” understanding of the mystery of the faith. His whole project is to promote a “real” understanding—an experiential immersion into, and appropriation of, Christ’s Paschal Mystery. He wholeheartedly embraces the Council’s call to “full, conscious, and active participation,” but does not think of this only, or primarily, in terms of external actions. Rather, the liturgy calls us to contemplate and enter into the absolute newness of the crucified, risen, and ascended Jesus Christ. Participating in this newness “costs not less than everything,” as Bouyer’s friend T. S. Eliot cautions. The liturgy leads participants into a supernatural order that overturns “worldly” values—that new order announced in the Sermon on the Mount. Baptism is not to be understood as just a sociological identity card; it is a new birth, a birth “from above.” Like physical birth, moreover, Baptism is only the beginning of a journey, one that requires an ongoing transformation “from glory to glory” (2 Corinthians 3:18), until “Christ is all, and in all” (Colossians 3:11).

Bouyer’s Introduction to the Spiritual Life, though written prior to the Council, is as challenging today as it was when it first appeared in 1960. Long before Vatican II issued its “universal call to holiness,” Bouyer recognized the connection between holiness and full participation in the liturgy. He firmly believed that mysticism is not some esoteric phenomenon, reserved for an elite, but is instead the full flowering of the life inaugurated in Baptism. It is “nothing other than the most profound apprehension to which we can be led by grace here below—apprehension of the truths of the Gospel, the realities of the sacramental life which the Christian accepts by faith and makes his own by charity.” Bouyer went further: “Mysticism follows the vital logic of a life of faith fully consistent with itself.” Full, conscious, and active participation in the Church’s liturgy thus entails the perception of this vital paschal “logic.”

If this view of mysticism seems extravagant, recall the famous (if little heeded) prophecy of Karl Rahner: “The devout Christian of the future will either be a ‘mystic,’ one who has experienced ‘something,’ or he will cease to be anything at all.” But I think Bouyer provides a fuller sense of the shape, content, and implications of such mysticism than Rahner does, not least because Bouyer insists from the beginning that the “experience” in question is not of “something” but of “Someone”—the Paschal Christ encountered in the liturgy, especially the Eucharist.

Together, Christian Initiation, Introduction to the Spiritual Life, and The Paschal Mystery form a rich trilogy. The first book draws readers into a series of discoveries: from the discovery of the spiritual world, through the discovery of God, to the discovery of the new life in Christ. The second book sets forth the dimensions of that life and the spiritual exercises and practices that nourish it. The third book, as we have seen, ponders the Paschal Triduum as the Mystery’s fullest expression and embodiment.

In addition to these three books intended for a general readership, Bouyer also wrote three other trilogies that are less known and more theologically speculative. Written over a period of almost forty years, these trilogies address, respectively, God’s “Economy of Salvation,” “The Doctrine of God,” and “The Hermeneutics of Scripture and Tradition.” Keith Lemna, who is bringing these books again to the attention of the theological community, calls Bouyer’s nine-volume work on dogma “one of the most far-reaching syntheses of the meaning of the Christian mystery, in its interconnected dimensions, in the twentieth century.”

Lemna devotes special attention to Cosmos, the third volume of the trilogy on the economy of salvation. He considers this book to be “Bouyer’s most personal as well as most speculative work,” one which “opens up the meaning of his other writings.” Here, according to Lemna, Bouyer “aims to show the radical newness of the Christian way of seeing the cosmos and the transfiguring Wisdom of God that God’s revelation discloses and imparts in the folly and power of the Cross.”

Reading Lemna’s careful studies of Bouyer’s systematic trilogies, I was reminded of an insight of Charles Taylor in A Secular Age. Having acknowledged and affirmed modernity’s accomplishments, Taylor forthrightly diagnoses its deficiencies. He suggests that it tends to produce people who are deracinated and disembodied. They live within a constricted “immanent frame” and shield themselves from the encroachments of others by means of what Taylor calls the “buffered self.” His word for this whole dynamic is “excarnation”—the opposite of incarnation. In the final chapter of A Secular Age, titled “Conversions,” the Catholic philosopher issues this striking appeal to his fellow believers: “We have to struggle to recover a sense of what the Incarnation can mean.” Taylor then quotes the French poet Charles Péguy: “One is Christian because one belongs to a race which is re-ascending, to a certain mystical race that is spiritual and carnal, temporal and eternal.” Because Christianity is faith in the incarnate God, there can be no repudiation of matter, no relapse into excarnation.

What Péguy poeticized, Bouyer theologizes, in both his more pastoral and his more systematic works. Bouyer shares with Péguy an acute sensitivity to the corporeal and the communal, a conviction that our access to God cannot bypass the material creation and the concrete Church, which is the very body of Christ. What Bouyer adds is an intense appreciation of the cosmic horizon of the Christian mystery, taking with utmost seriousness Ephesians 1:10, which speaks of the “recapitulation” of all things in Christ. As Lemna puts it, “Matter can be transfigured. In fact, this is why it exists. The illuminated body of the transfigured Christ on Mount Tabor is paradigmatic, and the Mystical Body of Christ is the ultimate instrument of the transfiguration of cosmic being.”

Another important (and somewhat neglected) theme in Taylor’s A Secular Age is theosis, or divinization. Taylor speaks of it as “the further greater transformation which Christian faith holds out, the raising of human life to the divine (theosis).” What Taylor (via Hopkins and Péguy) hints at, Bouyer brings to full light. Deification does not happen to the isolated individual. Rather, it is personal—that is, a relational and communal consummation. As Lemna writes of Bouyer’s view, “In the eschatological Church, we shall enter, in the unique person of the Spouse of the Lamb, into a perfect condition of relationship with the Trinity, such that our deepest human capacity as essentially relational beings is actualized.”

From early on, Bouyer clearly saw that the full unfolding of Jesus’ Paschal Mystery had to involve all Christians in their intimately interrelated humanity. Only together, only in communion, could they image the Triune God and herald a new divinized creation. In The Paschal Mystery Bouyer writes, “By our new and supernatural subsistence in Christ, founded upon the Incarnation and maintained in all of us by the Eucharist, we form a single new being in the body of Christ, or, more exactly, in the whole Christ, in the plenitude of Christ.” He concludes: “New relations are established between us, uniting us indissolubly, since henceforth we all have no longer but a single life—that of Christ in us.”

In fact, all of Bouyer’s writings can be read as one long commentary on Paul’s teaching that Christ “died for all, that those who live might live no longer for themselves but for him who for their sake died and was raised…. Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation, the old has passed away, behold the new has come” (2 Corinthians 5:15, 17). That formulation sounds simple enough, but, as Bouyer showed, its implications are inexhaustible. For Jesus Christ’s Paschal Mystery unfolds into the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and life everlasting.

When Bouyer died in 2004, the archbishop of Paris, Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, preached the homily at his funeral Mass. Lustiger had once been a student of Bouyer’s, and he spoke about how the theologian had “reopened for us the great paths of the Tradition, not by ignoring the trials and contradictions of the present, but by teaching us, on the contrary, to confront them and to bring to bear an attitude both open and critical, finding our delight in an even deeper understanding of the Christian Tradition.” In his posthumously published memoirs, Bouyer described his career with disarming modesty: “I believe that I was born to teach, and to teach the Christian religion as the only possible inspiration for a humanism that is not a pipedream. My books strike me as no more than the fruit of a lifetime of work. They remain, simply, the output of an honest and competent professor. My priestly ministry contributed to their elaboration far more than the other way round.” But Bouyer was more than just competent. His writings on liturgy were ahead of their time; they may now deserve a second look—or a first look—from a new generation of theologians. As for the rest of his work, it is arguably still ahead of its time. If we give it the attention it deserves, it may help us both to appropriate the full Christological richness of the Second Vatican Council and finally to move beyond the ecclesial polarization that followed it.

Works Drawn Upon

Christian Initiation

Louis Bouyer

Introduction by Michael Heintz

Cluny Media

$19.95 | 172 pp.

Introduction to the Spiritual Life

Louis Bouyer

Introduction by Michael Heintz

Ave Maria Press

$19.95 | 416 pp.

The Paschal Mystery

Meditations on the Last Three Days of Holy Week

Louis Bouyer

Introduction by Michael Heintz

Cluny Media

$24.95 | 404 pp.

The Apocalypse of Wisdom

Louis Bouyer’s Theological Recovery of the Cosmos

Keith Lemna

Angelico Press

$22.95 | 526 pp.

The Trinitarian Wisdom of God

Louis Bouyer’s Theology of the God-World Relationship

Keith Lemna

Emmaus Academic

$49.95 | 440 pp.