THE DRAMATIC closing in September, 1977 of the Youngstown Sheet & Tube Campbell Works steel mill has made Youngstown, Ohio, a synonym for economic crisis. The equally dramatic efforts of area clergy to save the 4200 jobs lost there has been proclaimed as a model for citizen action to confront those economic problems shared by cities throughout the northeast. Youngstown's Ecumenical Coalition of the Mahoning Valley has mobilized church groups throughout Ohio and the nation behind the goals of corporate accountability and economic self-reliance. It has created what amounts to a political machine to demand state and federal aid in the massive task of resurrecting the closed Campbell Works.

In spite of these efforts, the Commerce Department's Economic Development Administration has recently rejected the Coalition's request for federal loan guarantees to purchase and run the Campbell Works as a community- and worker-owned co-operative. But it would be a mistake to assume we have heard the last of Youngstown. For all the publicity which has surrounded the Ecumenical Coalition and its project, what may prove to be the most lasting feature of Youngstown's drama has been missed. The complicated response of Mahoning Valley steelworkers themselves—both to the mill closing and to the Coalition's attempt to reopen it—is the real story in Youngstown today. This response can only be reinforced by the government's decision. It is the last chapter in a saga which has been fifty years in the making.

For the crisis these men are living is not exclusively economic but cultural; it is the cultural crisis of Youngstown's working class. These men are witnessing the break-up of a particular form of social life shaped by the growth of the American steel industry, the labor struggles of the '30s, and the three-way partnership among big government, big business and big labor which was forged during the Second World War and has lasted ever since. They are caught between their desire to save that culture and their growing realization of the necessity of change.

I

WHAT ONE first hears in the voices of Mahoning Valley steelworkers is their anger. Anger at the Lykes Corporation, the New Orleans conglomerate which owned Sheet & Tube and, without warning, ordered the closing of the Campbell mill; anger at the government and politicians in general who have done next t o nothingto stop it. A local union official sums it up: "We've heard all the words from politicians and businessmen and lawyers, and no one has any ideas."

"Maybe I seem like a Communist or something," says Joe Lukas, still not quite comfortable with his role as critic, "but our government is just selling us down the drain. I don't think the people have enough control." Joe is a political conservative and strictly speaking not even a 'worker' at all. He used to be a foreman at the Campbell Works.

Joe is unemployed now but thinks he has found another job. This does not soothe his anger, however, nor erase his sense of loss. He cannot think merely in terms of his own personal economic future but is constantly drawn back to the misfortune of the Valley as a whole. For Joe Lukas, an entire region has been laid off. Since 1950, over 100,000 jobs have been lost in the Mahoning Valley due to industrial closings. Joe lists product after product which used to be made here; now the factories are down south or abroad. He describes the steel mills that have been closed. And when he speaks of the Campbell Works itself, the depth of his loss is apparent. "Since I been two or three years old, I seen that mill. You always knew when they were pouring steel even though you couldn't see it. Then all of a sudden you see the place dead. I worked there for years; still go by just about every day. 'Course you're not allowed in there now, you're out."

For Joe, the mill is more than just a work-place, it is the focus of a way of life. Now he feels like an outsider, dispossessed. Behind his anger, there is incomprehension, a lingering sense of promises not kept. "Living here all my life, I see these things, just like sand castles washed away. I can't understand why; if you talked to other people, they would say the same thing."

George Limberty is 48 years old; he has worked in and around the steel industry all his life. His two previous jobs— one in a furniture factory which used steel tubing, one in another mill—were moved out from under him. He had been working at Youngstown Sheet & Tube for eleven years when the closing announcement came.

George and his wife had just returned from a trip to Florida when I spoke with him. "We figured 'what the beck,' let's take the last TRA check and just go. For our peace of mind." TRA (for Trade Readjustment Allowance) benefits are special federal stipends to workers who have lost their jobs as a result o f international trade policy. The increase in foreign steel imports during the past few years makes Youngstown workers eligible for these benefits. Between state unemployment, industry "supplementary unemployment benefits" (SUB), and federal TRA benefits, unemployed workers from the Campbell Works collect between six and eight hundred dollars a month. This sum has kept the majority from feeling the economic pressures of unemployment in the 18 months since the lay-offs. Many of these benefits, however, have begun to run out.

Even with these social welfare services, unemployment has been difficult for George. It has not meant economic hardship but psychological strain. "It's very frustratingto be kicked out like that when you feel you've done a good job, to lose a job like that and have no way to fight back." Occasionally he has dreams about the Campbell Works—the mill still running, him still working. "You try to forget about it but it comes back in your dreams. That shows that you haven't really got it out of your mind." Even the generous benefits that keep him and his family going have become a source of frustration. They pacify and defuse his anger. "It's like burial money. You lay around for a year and then you're disorganized."

How do Mahoning Valley steelworkers cope? Of the original 4200 men laid off, about 1500 decided to take an 'early retirement' under various pension plans that the United Steelworkers union has arranged with the steel industry in the event of mill closings.The '80' plan provides forearly retirement for those whose sum o fyears o f service plus age equals or surpasses eighty. A '70' plan also exists but it is limited to those men at least fifty-five years of age. The more accurate term is 'enforced' retirement. "It's not like they wanted to retire," says George Limberty. "They figured that it's that or be a laborer."

Other workers who did not qualify for early retirement but still have high seniority have been relocated at other Youngstown Sheet & Tube facilities. But these men, often highly skilled, must enter a new mill at the lowest wage and skill levels. Such jobs are in no way equivalent to their previous positions at the Campbell Works. And when such men are relocated, they take over the jobs of younger workers with less seniority.

Neither of these options is open to George Limberty. He is among the 1500 ex-Campbell workers still without a job in the Youngstown area. Because he has only eleven years seniority, he is in the position of a young worker looking for a new job with another company—with the added disadvantage that few companies will hire a 48-year-old veteran of one heart attack. George has applied for CETA funds to learn a new skill; he has been told there is a long waiting list, nothing has come through yet. He has also tried to look for work at other mills but generally, he says, one has to have pull, some kind of connection. Out of work for more than a year now, George is getting worried. TRA benefits have run out; the SUB fund is near depletion. "Everything is just startin' to fall out now."

George Limberty was a pit-coordinator at the Campbell Works. He liked the variety of his job. "I was always doing different things. I never got bored." Source of financial security and interesting work, it was the foundation on which he constructed his life. Without it, he feels disoriented and lost. The closing of the Campbell Works has undermined his sense of purpose and identity. His response has been to become a firm supporter of the Ecumenical Coalition's community ownership project. He has done volunteer work, set aside his $2,000 savings in a special "Save Our Valley" bank account, written letters to congressmen, senators, even the President. His justification for his support is simple: the Coalition is the only group trying to do something to safeguard the jobs of the Mahoning Valley steel industry.

According to Ed Mann, president of United Steelworkers Local 1462, men like Joe Lukas and George Limberty are typical of Coalition supporters among area steelworkers. They are in what another local president, Bill Sferra, terms "the gray area"—too young to take early retirement, too old to easily find another job. Both the old and the very young are skeptical of efforts to resurrect the mill. "Why bother?" they say. Safeguarding the Campbell Works jobs doesn't mean that much to them. But to the men in the gray area—in the middle years of their work experience with mortgages and car payments, perhaps even children in college—the threat to their livelihood cuts far deeper. It goes beyond the narrow parameters of job and workplace to challenge a certain understanding of the world, certain expectations that have been built over the years. In the process, these men—the 'establishment' of Youngstown's working class—are coming to realize the degree to which traditional political and economic institutions must change in order to meet the challenge at hand.

II

THIS IS most true for the steelworkers' union itself. Throughout most of the struggle to reopen the Campbell Works, the union bureaucracy has been skeptical about efforts to save its members' jobs. The stories one hears in Youngstown describe a leadership unwilling to recognize the seriousness of the closing threat. United Steelworkers president Lloyd McBride is reported to have claimed at one meeting that mill closings fell outside the boundaries of collective bargaining. George Limberty reflects a common sentiment in the Mahoning Valley: "The guys that are runnin' the union now are from the old school. They're working' hand in hand with management against us."

This judgment is unfair; there certainly has not been any labor-management conspiracy against the Coalition's project. But the Youngstown situation does present a range of problems which historically have been beyond the pale of union activity in America. When mills and factories close, workers and communities begin to ask questions about investment decisions. Who makes them? How might the community control them? Community ownership is one proposed solution. Both the problems and the solutions cut against the grain of American labor relations. They confusethe clear-cut realms of management and labor; they do not fit easily into the highly structured practices of collective bargaining. Like most union hierarchies, the USW leadership is unaccustomed to dealing with these matters; many officials have been suspicious ofthe community ownership plan.

Russell Baxter is at the apex of the USW hierarchy in Youngstown. Senior president of the area locals, member of the AFL-CIO council, Russ claims close relations with international officials in Pittsburgh. His local, 2163, was the hardest hit by the Campbell lay-offs. Two-thirds of Russ's 3000 members were put out of work.

Since the Campbell closing, Russ has moved at crosscurrents to the rest o f the local union leadership. He is considered something of an opponent to the Coalition, although he claims he supports its attempt to "get what it can for Youngstown." Russ's oppositionis really an obsessive cautionand cynicism. He is cynical about his fellow presidents ("those sons o' bitches were just happy their local didn't get hit"), about young workers (who don't know what hard times are), about the Ecumenical Coalition (which is "offerin' false hopes"). But Russ doesn't seem to have much to offer in return. He avoids the issues o f lay-offs, plant closings, the problems of the Mahoning Valley steel industry. Instead he returns again and again to the hard times of the Depression, to how much he is doing for his men through his contacts with the international. In fact, Russ has done, can do, very little. By the end of our conversation, he virtually admits it himself. "These are deep subjects," he says with an uneasy mix of humor and self-deprecation, "and I'm just a dummy."

More accurately, Russ is unequipped to deal with the closing of the Campbell Works. His kind of unionism was never meant to handle the shut-down of a mill, the agony of an entire industry. He can only continue in his ways, using the time-tested old methods. He talks of collective bargaining and benefits, all the while complaining about the new generation and their lack of appreciation and commitment. "They never even come around the union hall anymore!"

Ed Mann is president of the "Brier Hill" local, 1462, one of the most militant in the USW. He was a founder of RAFT—the "Rank-and File Team"—a movement for internal democracy within the union in the 1960s. Ed was also a strong supporter of dissident candidate Ed Sadlowski in his challenge to McBride for the presidency in 1977. Sadlowski carried the Youngstown district by a vote of five to one.

Ed lost 200 of his 1500 members when the Campbell Works was closed; he expects to lose the rest when Jones & Laughlin Steel Company, the new owner of Youngstown Sheet & Tube, shuts down the Brier Hill facility later this year. Unlike Russ Baxter, he belongs to a small group of local union officials who have pushed the idea of community ownership from the beginning. According to local 1462's recording secretary, Gerald Dickey, "in the early stages, people were open to the idea, but then the political dimension comes in and people got scared." Not wanting to cross the international, local workers informed Pittsburgh of their discussions. The union sent a lawyer to advise them and "that killed it."

When I talked to Ed, he felt caught between the anger and disillusion of his men and the inertia o f the international. "We'vegot guysin the mill who were run out ofWest Virginia and Pennsylvania when the coal mines went bust. And now it's happening here." Whatdoes Ed want to do? He cannot say in any detail. "We don't have a plan. The problem is we only do something when something happens to us. Weonly react." He is determined to start considering alternatives to the Brier Hill closing now, not to get caught by surprise and put on the defensive as the Campbell workers were. The officers of 1462 have asked the Coalition for help; they have also written Jones & Laughlin demanding a meeting to discuss the mechanisms of the shut-down. "We want ideas," says Ed Mann. "I've never been frightened of an idea in my life. But a lot of people are. And a lot of them are in the higher echelons of our union."

In late March, the United Steelworkers finally came out in full support of the Coalition's community ownership project. In a letter to President Carter, Lloyd McBride urged the federal government to approve Youngstown's Urban Development Action Grant, providing the seed money to purchase the mill. Even more important, the union, in consultation with workers laid off by the Campbell closing, devised a plan to cut labor costs by 21 percent in the reopened mill. Workers for the new company, christened "Community Steel," would forego seniority rights and receive other benefits in the form of stock ownership rather than wages.

What explains the union turnaround and why was it so long in coming? Ed Mann credits rank and file pressure from Youngstown locals. Coalition leaders consider their success at putting together a qualified management team to be the turning point. According to union leaders themselves, considerations of feasibility were ultimately decisive. Jim Smith, McBride's liaison to the Coalition, says that only recently was the community ownership proposal detailed enough to be "realistic."

All these reasons, and others, have nudged the USW into important new territory. The union has not exactly taken a leadership role in Youngstown, but the problems it has been forced to face there have inaugurated a necessary learning process. Youngstown has contributed to a new awareness on the part o f the union of the multiple and deeply rooted problems of economic dislocation. The precedent-setting agreement on labor costs is one example of this; a conference at Pittsburgh headquarters last month on the relative costs and benefits of constructing new mills versus modernizing old ones is another. Whether or not highly visible union support from the very beginning would have made the difference in efforts to reopen the Campbell Works is of course impossible to tell. At the very least, new kinds o f questions are being asked, the consequences of which will be seen in the years to come.

There are some young steelworkers in the Mahoning Valley who have chosen neither migration in search o f new jobs nor cynicism about maintaining the old ones. They are often lower level union officials—grievance committee members, safety representatives, or recording secretaries like Gerald Dickey. A few days after the announcement o f the eventual closing of Brier Hill, Gerald told me: "If you wanted to have a revolution in there, the day to do it was Monday. Those guys were mad enough to try anything." But the problem of how to act remains. How to confront the seemingly intractable difficulties that face the outmoded mills o fthe Mahoning Valley. For all the hopes raised by the Coalition's plan, Gerald is worried that they have waited too long. "The problem is you've only got a short time-period to do somethin'. Things got started too slow. It'll take a miracle now to do it." And Ed Mann admits, "Community ownership is still a strange idea because people haven't seen it work."

Gerald tells as story about going to hear Gus Hail, chairman of the American Communist Party and former Youngstown steelworker, give a talk. He went, not because he was interested in "that Party bullshit," but to find out what things were like in Youngstown's mills during the Depression. He relates Hall's anecdotes about his organizing days with the United Steelworkers' "Flying Squadron," the day at the Stop Five mill when armed company police fired on the strikers. "When you think of what those guys had to go through, and yet they won, they organized." For Gerald, it is a story of hope, "Maybe we'll win too." But just as in the '30s, new ideas and new practices are necessary. Gerald knows it will not be the old-timers—neither Russell Baxternor Gus Hall—who will invent them.

III

BY THE END of March, the Ecumenical Coalition was ready to present its most complete proposal to the federal government. Technical questions raised after the original feasibility study last year had been answered. A detailed survey of over 600 potential purchasers within 200 miles of Youngstown reported more than adequate markets for the new firm. The original request o f $300 million in loan guarantees was pared to $245 million. The agreement with the union had significantly reduced labor costs and the commitment of a major U.S. steel company president to serve as chairman of the board of Community Steel inaugurated the assembly of a management team. Finally, technical consultants had drawn up a 20-year income forecast which projected a profit-making firm within three years.

EDA's rejection came just a few days after this new information was submitted. In a meeting with Coalition leaders, presidential aide Jack Watson made it clear that the Commerce Department decision was made with the knowledge and support ofPresident Carter. Administration officials indicate two reasons for the refusal—the amount of the loan guarantee request and the overall weak economic basis of the proposal. Neither is especially persuasive. The $245 million figure does greatly exceed the EDA's official $100 million limit on loan guarantees, but the government has known that this would be the case since last fall. At the time, Watson gave the strong impression that Youngstown was a special case to be judged on the feasibility of the project itself. While it has been no secret that Commerce Department analysts have been skeptical of the plan from the beginning, the fact that they simply ignored the Coalition's latest studies (funded by $100,000 of government money) raises serious doubts about the economic foundations of their arguments. "We saw no indication that they even considered our most recent proposal," says Chuck Rawlings, an Episcopal priest who has been a key leader in the Coalition's efforts. "We had the sense that they had decided long before without telling us."

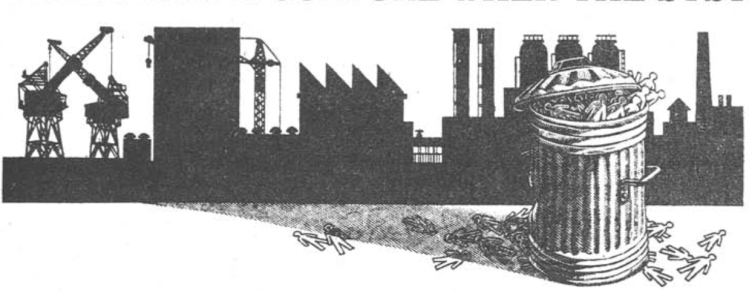

On May 31st, the Ecumenical Coalition's option to buy the Campbell Works will expire. While its leaders prepare a pastoral letter drawing the moral implications of the government's decision, technical consultants are trying to formulate an alternative plan—a project on a smaller scale involving less government money and employing less workers. There is also some talk of trying to make the community ownership project into a political issue, using the weight of labor support to pressure the administration to reconsider. Time, however, is very short and as yet there are no signs of how such a strategy might work. Meanwhile, the expected Brier Hill closing and cut-backs at U.S. Steel's Youngstown works will put 4100 more Mahoning Valley steelworkers out of work before the end of the year. Youngstown's crisis can only get worse.

It has been conventional wisdom among opponents o f the Ecumenical Coalition and in certain publications of the national press that Mahoning Valley steelworkers do not really support its efforts. "The Coalition is all leaders and no followers," according to a local sociologist at Youngstown State University. "It's embarrassing," admits Bill Sferra, "not too many think it will work in reality." Such judgments hide as much as they reveal about the response of Youngstown's steelworkers. For if they have been restrained in their active support, they have also been anxious to see the Coalition succeed. Ed Mann explains: "Workers aren't aggressively activists. We've been taught over the last thirty years that movements aren't clean. You can't expect dramatic changes in that attitude over the course of one year."

Thus, what might be termed the "passive support" of these men has been high. Many, including those only marginally aware of the Coalition's work, tell stories of old-timers who would come out of retirement to help start a community-owned mill, of young workers moved on to mills in Indiana who would return. "They'll come back in a minute," says one worker, "you see, their family is here; this is home." Or in the words of another, what is necessary is "a company we can trust."

Today, Youngstown's workers find it hard to trustanybody. One by one, the traditional markers of their social world— mill, job, union—have proven unsure. The government's decision only fuels their anxiety and their discontent. These men know that their needs are not being met. Increasingly they see that the old systems no longer deliver.

This context sets the boundaries for both the accomplishments and the dilemmas o f the Ecumenical Coalition o f the Mahoning Valley. Because Youngstown's crisis is in so many ways a crisis of traditional values, the community's churches have been drawn into the central role. In a sense, this role is a 'conserving' one but its political implications are far from 'conservative.' The Coalition is the defender of Youngstown's traditional working class culture. It searches for a means to maintain that culture in the face of far-reaching economic change. This is a complicated task, for in order to sustain the values that area workers hold dear—a sense of community, financial security, a job with which they can identify—that local culture itself must change. It must open itself to new ideas, new practices, new institutions. In such confrontations between culture and change, social innovation is born. Therein lies the immense potential of Youngstown's Ecumenical Coalition. Like the unemployed steelworkers o f the Mahoning Valley, this potential will not just fade away; it is built into the pain and promise of social changes which will be with us for a long time. Youngstown's last chapter may also be its first. —Robert Howard