Disney’s 102 Dalmatians, the 2000 sequel to the 1996 remake of the 1961 original, begins with the reformed Cruella de Vil’s release after three years in a London prison. Her psychologist Dr. Pavlov, who, like his namesake, relies on conditioning, has cured her of her desire to turn dogs into fur coats. But there’s a big problem: the conditioning can be reversed by loud noises. Sure enough, when Big Ben tolls, Cruella, driven mad and hair standing on end, rushes out onto the street. In her hysterical state, everyone looks like a Dalmatian—spotted white clothes and greasy white face paint with black pockmarks. To the seven-year-old me, watching this unfold during movie day in second grade, the Dalmatian people looked like clowns, who utterly terrified me at the time. I ran out of the classroom and holed up in the library, bawling my eyes out.

My teacher spoke with my parents and said I needed therapy. My therapist, a Freudian of sorts, determined that my fear stemmed from a belief that clowns were lovable human beings trapped beneath a wall of subjectivity-suffocating face paint, pitiable creatures, controlled mind and body. His treatment plan: I would paint my father like a clown to prove to myself that the thinking, loving person beneath the white make-up could still ponder and pity, hug and cheer. Dutifully, my father sat as I pressed his soul beneath the paint. I was cured. I decided that day that I wanted to become a child psychiatrist.

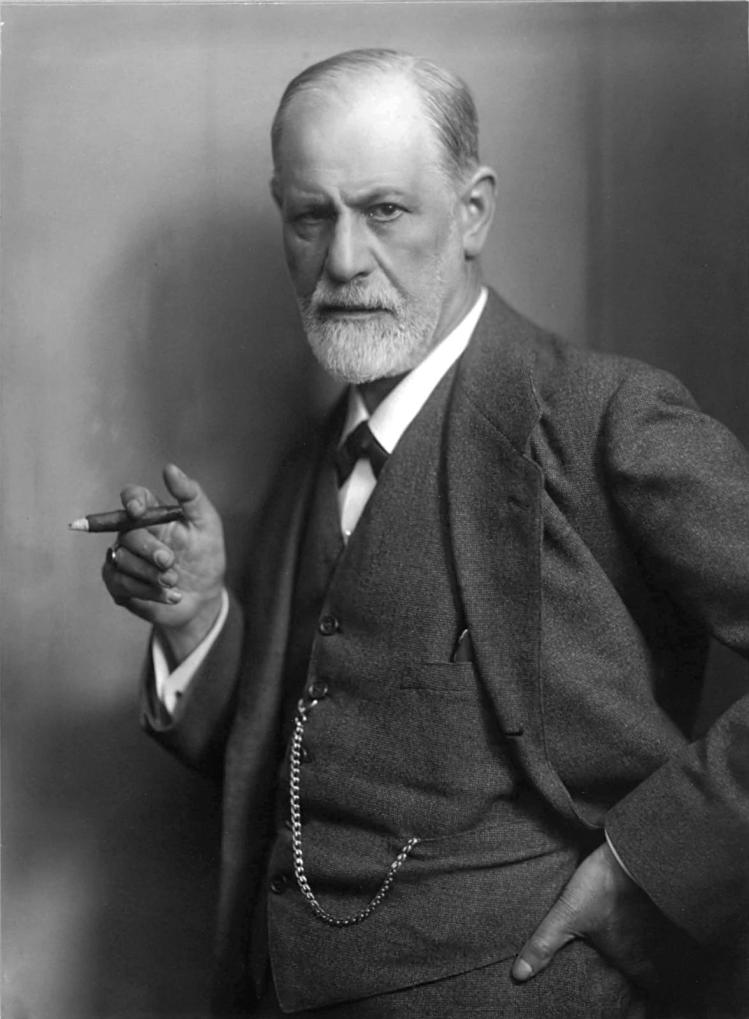

I kept recalling my clown therapy as I read the collection On the Couch: Writers Analyze Sigmund Freud, edited by Andrew Blauner. This volume varies as much as the writers themselves, ranging from stories of trans penis envy (or the lack thereof) to confessions of life as a member of the extended Freud clan to moving recollections of a daughter’s life and suicide. What makes them cohere is the authors’ inability to escape Freud’s influence. Many of them haven’t been able to shake him since childhood.

Critic and essayist Sarah Boxer feels her first memory—her father asking her as a newborn to bite his finger—is disfigured by unwanted, “kind of kinky” sexual tension. “Thank you, Sigmund Freud,” she writes. Phillip Lopate proudly remarks that “my own mother, though working-class, managed to scrape together enough dough for her weekly therapy sessions.” Lopate still defends Freud at cocktail parties now. The volume’s authors, mostly older, give the sense that not so long ago, Freud was everywhere, floating on the tongue of every Brooklyn Jew and suburban WASP housewife, ready to leap at the slightest opportunity for psychosexual insight.

Freud’s influence waned during the 1980s and 1990s, in part because of the so-called “Freud Wars,” during which critics like Frederick Crews took psychoanalysis to task for a lack of scientific support or clinical success. Crews tried to put a final nail in the coffin in 2017’s Freud: The Making of an Illusion. But, despite the criticism and the precipitous decline in Freudian analysts, Freud’s ideas never quite went away. In a review of Crews’s mammoth biography, George Prochnik offered an explanation. Ideas like repression, hidden parts of the self, and the half-scrutable language of dreams “in the forms they circulate among us, are indebted to Freud’s writings.” The name Freud might have become mud for a time, but his thought seems to keep speaking to us from below the surface, almost as if from our unconscious.

Is he poised to break through again? Some detect a “Freud resurgence” underway. Hannah Zeavin, founding editor of Parapraxis, a magazine devoted to psychoanalytic thought, remarks in the Chronicle of Higher Education that the old man’s back again, perhaps because of all the psychosocial trauma of recent years. New York Times reporter Joseph Bernstein, in an article titled “Not Your Daddy’s Freud,” documents Freud’s new presence on social media, in popular culture, and on the couch itself—in clinical practice.

On the Couch offers another way in which Freud has returned: some are beginning to take him seriously once again as a scientist. In essays by Richard Panek and Mark Solms, we are treated to remarkable tales of Freud the doctor. The young neurologist invented a new dyeing technique helpful to microscopy. And his early research into eel genitalia—the reproductive cycle of the species remains surprisingly mysterious—shines a new light on Freud the talk therapist.

This experience in hard science seemed to push the young Freud toward materialism. Writing to his colleague and friend, Wilhelm Fliess, Freud bragged that he had received a “clear vision” of the relationship between the physical brain and the neuroses of the mind. All could be reduced to physical matter. Fears, desires, totems, and taboos—all downstream from the soft tissues of the brain.

In the volume’s final essay, Siri Hustvedt informs us that Freud is now enjoying a renaissance in neurobiology. Inspired in part by his later insights, the field of “neuropsychoanalysis,” incorporating the findings of neuroscience and psychoanalysis in the name of mutual enrichment, has been born. With the scientific evidence turning against SSRIs and the view that depression is caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain, Freud, in a surprisingly materialist form, may be making a comeback in science.

As a sophomore in high school, I began to abandon my quest to become, like Freud’s daughter, Anna, a pediatric therapist. I fell in love instead with novels—Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge, Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Melville’s Moby-Dick. Literature seemed a better way of getting at people. Words on the page brought to life the inner workings of the human mind in a way no simple recounting of trauma ever had. Plus, I wasn’t much for science and math.

On the Couch analyzes Freud the author as well. Nothing less should be expected from its contributors, professional writers who exhibit a love of Freud’s art. Many of them go even further than mere admiration for his prose. They believe they owe their love for the craft itself to Freud’s discerning pen.

David Gordon, for instance, sees Freud as a Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot whose case studies read like true-to-life mysteries. During a “a gloomy autumn day at the beginning of the last century, or the end of the one before,” Gordon writes, in a “comfortable, well-proportioned room,” an “imposing but polite gentleman” puffs away on a cigarette and demands to know what’s wrong. Isn’t this, Gordon asks, the setting for a gumshoe of the mind whose case studies rival Poe’s for thrills and Conan Doyle’s for ratiocination?

Adam Gopnik sings his praises as an essayist, a regular disciple of Montaigne, while Colm Tóibín considers Freud’s contributions to letters alongside those of Henry James and Thomas Mann. Phillip Lopate speaks for all them when he lauds the minutiae of Freudian style: “I was charmed by his voice, his rhetorical syntaxes so reasonable sounding and engaging on their way to being shocking…. He was the explorer, a bearded Moses leading his people.”

Freud the writer is also Freud the literary theorist. As noted throughout this collection, psychoanalysis’s power, like that of literature, lies in its fascination with human subjectivity. For example, free association, a cornerstone of Freudian technique meant to provide access to the unconscious, is also something of a literary exercise. Both psychoanalysis and literature posit that, even if people are biological machines, we are not simple, one-dimensional machines open to view. We hide ourselves from ourselves, resist those who want to help, and lie about why we seek help when we do.

Like a great novelist, Freud exposes our complexities with honesty and understanding and without malice. You can lie to social psychology students who ask you to participate in a survey for their theses. They don’t care; theirs is the domain of quanta, of the measurable and definite. Freud knows better. He knows you’re lying—to yourself most of all.

When I was a kid, I watched a cartoon called Time Squad, in which the heroes must jump back in time to prevent historical anomalies and put humanity back on the correct timeline. In one episode Dr. Freud has remained obsessed with hypnosis, his original profession, and become a mad scientist, turning people into animals and bringing the entire city of Vienna to its knees. The Time Squad succeeds only by convincing Dr. Freud that dream interpretation is a more effective means of treating patients. Here, even in the midst of the Freud Wars, a children’s TV show asked its viewers to take seriously Freud’s transition from hypnotist to psychoanalyst.

Sigmund Freud is more an Augustine than a Donatus, the schismatic Augustine opposed. His insights are no fad—we live in a world he helped form, and the ideas he originated live on in even the few who might not know his name. When I misspeak, I have uttered a “Freudian slip.” When a CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) enthusiast ruminates on their traumas, they are conceiving of themselves as a damaged being in a form handed down from the father of psychoanalysis. Even when a cigar is just a cigar, we tacitly admit that Freud’s interpretive method is usually on the right track.

Come to think of it, I don’t know if I came to know Freud from painting my father’s face or from watching cartoons. Did I know his name before my mom giggled at a slip of the tongue? Or, when like Chaucer’s Nun’s Priest, she made sense of my dreams? I’m not sure it matters. Freud was always there.

On The Couch

Writers Analyze Sigmund Freud

Edited by Andrew Blouner

Princeton University Press

$29.95 | 360 pp.