There’s a scene in Amarcord, Federico Fellini’s semi-autobiographical 1973 film based on his upbringing in Fascist-era Rimini, in which the director’s plucky adolescent alter-ego, Titta, and his prankster companions find themselves enduring a tedious series of lessons delivered by a set of hapless schoolteachers. One of them, a beret-wearing elderly woman, sneaks a flask beneath her desk and pours herself a shot as she launches into a point about art history: “Do you know, boys and girls, why Giotto is so important in Italian painting?” she drones on, hardly aware that some of her pupils have begun punching each other. “Well, I’ll tell you: because he invented perspective!” “PER-SPEC-TIVE!” her class chants back, as she conducts them with a cookie, waving it back and forth like a metronome before dunking it and taking a bite.

If Fellini is mocking the abysmal state of Italian primary education under fascism, he’s also lamenting how one of the most revolutionary moments in Western art history—the radical leap, in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, from the flat “Byzantine” style to the three-dimensional naturalism that dominated European painting until at least the early twentieth century—has, for many of us, been reduced to a piece of trivia, a fact learned by rote and quickly forgotten.

Indeed it’s hard for us now, familiar as we are with the many waves of abstraction, experimentation, and transgression that succeeded each other for the past hundred and fifty years, to grasp just how fresh and and startling perspectival painting was for medieval viewers encountering it for the first time. Even Dante and Boccaccio, rough contemporaries of Giotto, wrote the fresco painter into their own masterpieces, the Divine Comedy and the Decameron, each marveling at how close the human art of painting had come to resembling “God’s art”—that is, nature itself. That shift in painterly style—visibile parlare, “visible speech,” Dante calls it—was more than a matter of aesthetics or ornamentation. It also reflected a change in which subjects were considered worthy of attention. Embedded in perspectival painting was the conviction that spiritual and divine realities were present in the visible world, and that skilled artists, by imitating the hand of nature, could capture and share them with viewers.

Few paintings demonstrate this as neatly and compellingly as Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Madonna and Child (ca. 1290–1300), which opens and anchors Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350 at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, on view through January 26, 2025. The gold-embossed poplar panel, probably produced for private devotion, is small—just 28 by 21 centimeters, including the frame. But there’s a lot going on within this “simple” portrait of Mary holding the infant Jesus. For starters, Duccio, a contemporary of Giotto and the leading painter in Siena at the turn of the fourteenth century, has included an illusionistic red-and-white parapet at the bottom of the image, conjuring a new spatial recess that draws the viewer out of their surroundings and more deeply into the separate “world” of the painting. Duccio pushes that movement one step further with yet another detail, this one borrowed from ivory statuettes then popular in France, which would have reached Siena because of its strategic location along the Via Francigena, the pilgrim path stretching from Canterbury to Rome. With his chubby right fist, the child playfully grasps the white inner folds of his mother’s veil, raising them like a theatrical curtain to reveal a still-more-intimate space under Mary’s hood. The Madonna’s head and face, wearing an enigmatic expression of melancholy and tenderness, have an almost sculptural weight and palpability. That’s just where Duccio wants the viewer to land: face to face with the Mother of God.

That Duccio’s image originally functioned as an icon is evidenced by the twin singe marks at the bottom edge of the outer frame. The Met’s soaring gallery walls and darkened lighting, inspired by the interior of Siena’s duomo, make it easy to imagine this painting above an altar, glowing with the flickering light of candles, surrounded by plumes of incense and strains of chant. Most of the works on view in the exhibition—alongside Duccio’s, there are many by his pupils Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Simone Martini—are displayed not along walls but on pedestals within 360-degree display cases, drawing our attention to spiky nails and rusty hinges, small termite holes and thick wooden battens. That the show foregrounds the rough materiality of the works doesn’t make them feel any less “religious.” Just the opposite: it’s by presenting them less as “works of art” decontextualized for viewing in a museum than as functional objects originally created for use during worship (in the galleries, they’re surrounded by chalices, reliquaries, croziers, and monstrances) that the show helps us approach them with an uncommon measure of reverence.

That’s entirely appropriate, especially because Sienese art insists that the material world is the precise place—the only place—where God’s self-revelation is to be found. That’s the case with the eight panels, long separated but reunited for the show, that once formed the back predella of Duccio’s Maestà, which was once mounted above the central altar of the duomo in Siena. Recognizable in the scenes of Christ’s temptation by Satan are that building’s diamond-shaped tiled floors and striped black-and-white marble walls, as well as the terracotta roof tiles and red brick pavement lining Siena’s central Via Banchi di Sopra. As Duccio’s pastel panels pile up like a film strip, our eye is drawn to other mundane details: the ribs, oarlock, and bench in Peter and Andrew’s little fishing boat floating on the Sea of Galilee; the heavy wooden barrels from which the servants draw water at Cana; the glazed ceramic pitchers from which the wedding guests drink wine. There’s also the bulging bicep of the man who lifts the lid off Lazarus’s tomb, and the grimace of the man covering his nose with his cloak to avoid the stench. Their inclusion is no less important than the miracles Christ works in these scenes. It is in these bodies, in these objects, Duccio suggests, that Christ’s divinity is revealed and recognized.

We say “Duccio” but it would be more accurate to speak of “Duccio’s workshop,” since Sienese painting in the 1300s was a more collaborative form of art-making than what we’re used to now. The works were made by many hands, from the assistants who mixed the paints and filled in the background to the metalsmiths who burnished and tooled intricate patterns and filigrees into the gold leaf. Artists had theological collaborators too, almost always members of the clergy, who not only commissioned and paid for the works but dictated the order and iconography of the scenes, and who were unafraid to intervene whenever artists deviated from their wishes. (Recent X-ray analysis reveals that Duccio originally depicted Lazarus’s tomb horizontally, like Christ’s; he was then forced to paint it over, perhaps because his patron objected to the possibility of Lazarus’s grave being accorded equal dignity with Christ’s.)

But the early fourteenth century in Siena was also a period during which painters began making names for themselves, earning public recognition as masters, shopping their skills and securing contracts for their workshops in communes and courts throughout Italy. Even the Lorenzetti brothers, as collaborative as two artists have ever been—together they frescoed Siena’s civic ospedale, Santa Maria della Scala—had their individual inclinations, recognizable in two very similar Crucifixion scenes displayed in different sections of the show.

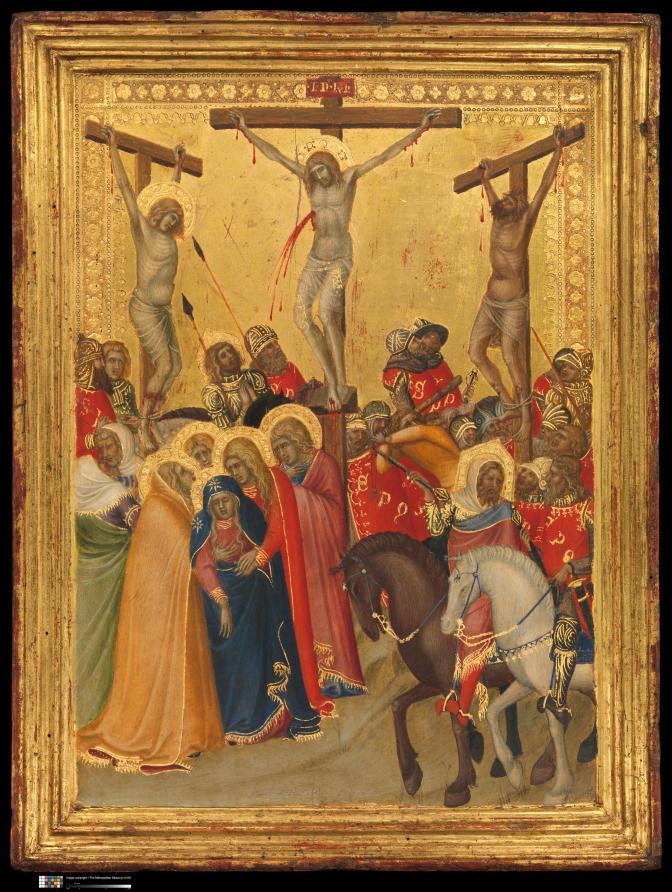

Pietro’s was probably made first, around 1340. Here, it’s as if he wants to convey the liveliness of the scene of Christ’s death: thick globs of bright red blood drip from Christ’s arms as a stream gushes from his side. In the background, we see three pairs of soldiers mounted on horseback, following each other horizontally across the frame, behind Christ. It’s a convention Pietro uses to indicate that each pair is really the same two soldiers; they reappear in the foreground, where one of them, with a square halo (the “good centurion,” who affirms Christ as the Son of God) indicates Christ with his mace. If we follow its line, we notice another figure in the middle of the crowd: an orange-shirted executioner swinging a club at the shins of one of the thieves crucified beside Jesus (it’s the “bad thief,” who mocked Christ; the other thief, with a halo, is already dead). The man’s legs, bound with rope, are bruised, suggesting the executioner has tried breaking them. But the executioner’s pinched face and square aim leave little doubt: this time the bones will shatter, and with his legs no longer able to support him, the crucified man will soon suffocate.

Pietro has thus introduced into the scene a different type of zoomed perspective: narrative time, depicted as the moment-by-moment unfolding of salvation in history. Ambrogio, by contrast, in a mature work completed just before his death in 1348—like his brother, he died during the Great Plague—depicts a Crucifixion that is at once more static and more poignant. A master of naturalism with an uncanny grasp of physics, Ambrogio orders the space with mathematical precision: Christ’s soaring cross, which divides the foreground down the middle, rises upward, anchoring a triangular frame like a pole holding up the center of a tent. Beneath Christ, on either side, are the same two groups we see in Pietro’s version: Mary and a few of the disciples to the left; Roman officials, including the good centurion and his companion, on the right. But Ambrogio gives us many more minutely rendered physical details, such as two horses arching their necks and lifting their front right hooves as their riders shift in their stirrups and tug on the reigns. Ambrogio is also more skilled at depicting emotions than his brother: Mary’s blue-clad body is splayed across the ground in grief, her head cradled in the lap of another haloed woman. Other onlookers—long-haired Mary Magdalene, a bearded young man, a young woman in a green dress—look upward at the dead Christ as if expecting him to rise. But to no avail: it’s as if everything and everyone in the painting is pulled down by the heavy, intractable force of gravity.

All this might make it sound as if the Met’s Siena show is a downer. It isn’t. There are plenty of works that demonstrate a kind of levity, like the fluttering polychrome wings and rippling robes of the Archangel Gabriel in Simone Martini’s Orsini Polyptych (ca. 1333–40), or the insouciant scowl and crossed arms of Christ as a petulant adolescent in his Christ Discovered in the Temple, from 1342. Still, a weighty solemnity does pervade the show. And that might actually explain why it has been such a hit, popular not just with critics and fans of Italian religious art but also, even especially, with nonreligious audiences. Medieval Sienese artists’ respect for the communal and their straightforward earnestness are everything the contemporary art world, with its six-million-dollar bananas taped to walls, is not.

It’s a cliché that art museums have become “sacred spaces,” replacing churches, synagogues, and temples as sites of connection and shared meaning for an increasingly pluralistic, nonreligious population. Like most clichés, this one has at least a grain of truth. Generally, you don’t go to the museum to pray, but that doesn’t mean that whatever you’re doing there—or out on the street, or on the subway, or in the park—can’t also be something transcendent. If the art of Siena, with its electric colors, exotic patterns, and fanciful imagery says anything, it’s this: God is everywhere, in everything. Finding him may simply require changing your perspective.