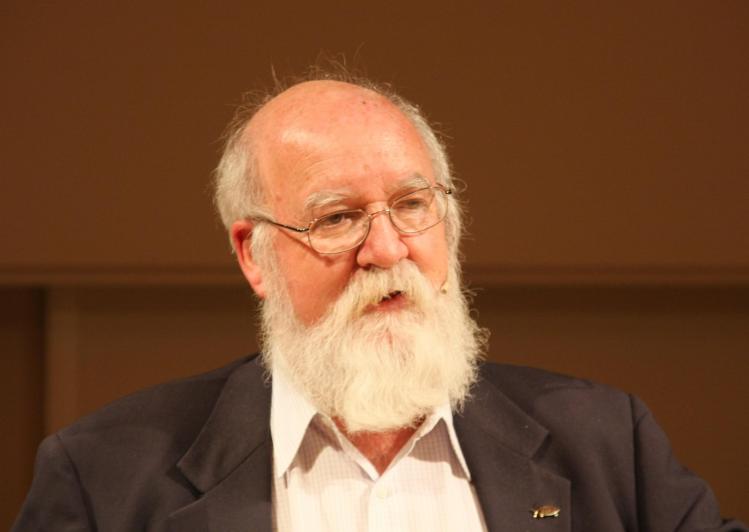

The latest book from the philosopher Daniel Dennett is a work of tremendous ambition. Its scope is displayed in its title: Dennett spins a story of the evolution of intelligence that begins with unicellular life and culminates in human genius and the capacity of the human mind to comprehend its own origins. Like all of Dennett’s writings, From Bacteria to Bach and Back is brimming with erudition, wit, and insight. He has always been one of the rare philosophers who can write in a way that is at once philosophically rigorous and accessible to an educated and interested non-philosopher. This new book is no exception.

Nor is it an exception to something that many readers will be less enthusiastic about—namely, Dennett’s unapologetically reductive understanding of life, consciousness, intelligence, and culture. This reductionism has two main aspects. First, Dennett holds that the behavior of complex systems, including living ones, is generated entirely from the interactions between their parts. Second, except in the special case where humans or other animals act as the “intelligent designers” of our tools or cultural artifacts, he also describes the evolution of complexity and intelligence in an entirely bottom-up way—as the result of blind selection pressures acting on simpler and less intelligent systems. Dennett explains the latter idea with a pair of images that are familiar from his other books: instead of “skyhooks”—mythical devices that hang from the sky in order to move things to new heights—nature makes use of cranes, which lift things from the ground up. Reductive explanations of the first sort mean that we don’t need souls or other distinctively higher-order principles to explain what happens in nature. Explanations of the second sort mean that no appeal to God or other supernatural powers is required to explain why things are the way they are.

Things are not quite so simple as that. For as Dennett acknowledges, there is more than one kind of explanation. Suppose, for example, that I ask you for an explanation of Donald Trump’s election to the presidency. One way to answer this request would be with an account of the causal factors that contributed to Trump’s victory. Such an account might discuss the role of the Electoral College in granting disproportionate power to rural states, the deteriorating economic situation of white working-class men, the effects of immigration, the influence of the conservative media, and the ways that misogyny and xenophobia may have made Trump and his policies popular. This account addresses the question “Why did so many voters choose Trump?”—where “Why?” is understood to mean “How come?” It is an attempt to explain what brought it about that so many Americans (enough, though not a majority) voted for Trump.

A second way to explain the same outcome would be in terms of the goals of Trump’s supporters, or their purpose in settling on him as their preferred candidate. There will likely be some contact between this sort of explanation and the previous one: Trump supporters wanted to restrict immigration, to improve the situation of white working-class men, and so on. But now these factors are treated not just as forces that made it likely Trump would win—as, for example, the structure of the Electoral College made this likely by giving more influence to the average Trump supporter than to his average opponent. As Dennett puts it, instead of answering the question “How come?” an explanation in terms of goal or purpose speaks to our desire to know “What for?” And the possibility of giving a how-come explanation of something in terms of impersonal, bottom-up forces doesn’t mean that the same thing can’t also be explained in terms of purposes or goals.

To illustrate this point, consider how we understand the growth of a tree. To explain how come a tree grows in a certain way, we might need to appeal only to factors like the genetic information in its cells, the nutrients in the soil, the chemical reactions involved in processes like photosynthesis, and so on. But the possibility of giving such a mechanistic, bottom-up explanation of the tree’s growth doesn’t mean that we can’t also appeal to goals or purposes in explaining what certain aspects of the tree’s metabolism or anatomy are for. The purpose of growing leaves, for example, is to help absorb energy from sunlight; the purpose of roots is to collect water from the ground; and so on. Just as we understand Trump’s election better when we appreciate the goals that motivated his supporters, this purposive or “teleological” explanation (from telos, the Greek word for “end” or “purpose”) of the tree’s growth captures something important that is not conveyed by a description of the cellular and genetic mechanisms that underlie this process.

For some scientists and philosophers who try to be especially hardheaded in their reductionism, talk of the purpose of roots or leaves is either foolish anthropomorphism (how can a mindless organism have goals of its own?) or involves a covert appeal to an intelligent designer whose purposes these are (e.g., perhaps God made trees have leaves because he wanted them to have a way to absorb energy from sunlight). To his credit, Dennett does not hold that teleological, what-for explanations of natural phenomena are all illusory or second-rate. He rejects the assumption that even mindless nature is necessarily bereft of purpose. There are, he says, purposes or “free-floating rationales” throughout the living world, and explanation in the biological sciences makes constant appeal to this natural teleology.

For Dennett, what makes the rationale of a process like photosynthesis or a structure like the roots of a tree free-floating is that this rationale does not need to be grasped or represented by anyone in order for it to be part of what explains a given phenomenon. In this respect, teleological explanation in biology is different from the explanation of human behaviors and artifacts in terms of our purposes or goals. Why did Jane go to the store? Suppose it was to get some milk: this explanation presumes that Jane believed that there was milk at the store, and that going to the store was a good way to get it. Why do hammers have flat heads? Because this is part of a clever design—our design—for driving in nails. But why do the roots of a tree grow outward? If it is in order to bring in more water, this need not be because the tree understands that an extensive root system will have this effect, nor because someone designed trees to be effective in finding nutrition. Rather, it just happens that roots are an effective way of absorbing water from the soil, thereby increasing the lifespan and improving the reproductive fitness of certain species of plants. For this reason, a process of natural selection that favors reproductive fitness was likely to lead to the spread of organisms that possess this favorable trait. This kind of rationale can exist whether or not there are beings like us with the capacity to comprehend it. The rationale for roots existed at least as soon as roots did—and long before human beings discovered what it was.

So far I have said nothing at all about the nature or origins of consciousness, which for many of Dennett’s critics is the point at which his reductionism goes to pieces. According to Dennett, the natural assumption that consciousness isn’t susceptible to scientific explanation is the result of a peculiar kind of illusion: each of us feels sure that we have a subjective life or point of view on the world that can’t be understood from an objective or external point of view. His critics contend that this position is simply a perverse denial of a basic reality for which Dennett’s theory has no room. But I think there is more to Dennett’s position than he is often given credit for. For example, philosophers who argue against Dennett sometimes do this by asking us to imagine “zombies” who can think and act in just the same ways that we do, despite lacking any subjective life. The conclusion we are supposed to draw is that the conscious subjectivity that is present in us but missing in the zombies is not the sort of thing that is amenable to explanation from an objective scientific perspective. But Dennett challenges us to think more carefully here: Would we be able to tell the difference between ourselves and these hypothetical zombies? Would the zombies be able to tell? If not, then it is hard to see what the purported difference between them and us is really supposed to come to.

This doesn’t mean I find Dennett’s reductionist account of consciousness entirely convincing; I think it’s quite possible that consciousness is impervious to reductive explanation. It’s hard, though, to explain why this should be without importing problematic assumptions about what conscious experience is.

Two other places where Dennett’s account is especially sketchy and incomplete concern the origins of life and the birth of human language. Any discussion of these topics is bound to involve a lot more conjecture than scientific detail, simply because these events occurred in the very distant past and left no fossil traces from which their course could be inferred. Moreover, on Dennett’s own telling, both of these are likely to have been one-time events, which means that we cannot use evidence of convergent evolution—in which a similar trait evolves independently in distinct species with different ancestral origins—to home in on a correct account of how life and language arose. While Dennett does his best to address these matters in ways that are both plausible and supported by the available scientific evidence, his theory is surely wrong at least in the details, and probably more than that. We’re simply not yet in a position to be confident about any detailed account of the origins of language or of life. For now at least, our theories are speculative and mostly untestable.

That situation could change one day. But whether or not it does, I think that anyone interested in defending an orthodox view of God’s responsibility for creation should want to do more than identify occasional explanatory gaps in scientific understanding that supernatural “skyhooks” might help to close. That approach makes it seem as if God’s role as creator were either in competition with the operation of natural mechanisms, or incidental to their operation—as in the Enlightenment image of God as a benevolent watchmaker who sets the mechanism of the universe in motion and then leaves it to tick away, perhaps intervening occasionally to adjust the gears or add some clever new widget.

What would a better alternative look like? Consider a famous passage from Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species:

As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever-branching and beautiful ramifications.

Is the generation of life like the growth of a tree? Alhough Dennett borrows this image frequently in many of his books, I am sure he would answer that, really, it is not. The growth of a tree is a process informed with purpose, whereas evolution by natural selection is a blind, purposeless process whose products include blindly purposive organisms like trees and termites, as well as self-conscious agents like ourselves, who can act with purposes we understand and design tools and other artifacts to help us achieve our goals. But this understanding of the process of evolution is not obligatory. Another possible response to Darwin’s description of the Tree of Life is the refrain of Aquinas at the end of each of his attempted proofs of God’s existence: Et hoc dicimus Deum—“and this is what we call God.”

Dennett touches on this last idea in an earlier book, asking in Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (1995): “Is this Tree of Life a God one could worship? Pray to? Fear?” Probably not, he says, though nevertheless “I can stand in affirmation of its magnificence. This world is sacred.” I expect that, were Dennett pressed to clarify that passage, he would add: well, not really. Whether we are able to say this kind of thing without backing down from it seems to me to matter more than Dennett is likely to admit.

From Bacteria to Bach and Back

Daniel Dennett

W. W. Norton, $18.95, 496 pp.