If I had discovered Joan Didion properly, I would have first read her books in a New York City apartment, alone with my gin and my despair, as yellow silk curtains fluttered listlessly in the breeze. Or possibly on a beach in Malibu, flowers in my hair and woe in my heart. Instead I picked up Slouching Towards Bethlehem one Saturday morning in the doctor’s office because I had broken a finger and the book was light enough to hold with one hand. Despite the un-Didion atmosphere, I was hooked.

Although she has written five novels, two memoirs, and several works of nonfiction, Slouching Towards Bethlehem is the book that made her famous. Ranging from reporting to criticism to memoir, her first essay collection introduces readers to Didion’s perfectly composed sentences and sharp eye for detail—and to Didion herself. “Since I am neither a camera eye nor much given to writing pieces which do not interest me, whatever I do write reflects, sometimes gratuitously, how I feel,” she wrote. Critics complain that Didion imposes her feelings onto stories, observing her emotions as closely as she observes the hippies of San Francisco. But for Didion, that’s the impulse to write down anything: “Remember what it was to be me.”

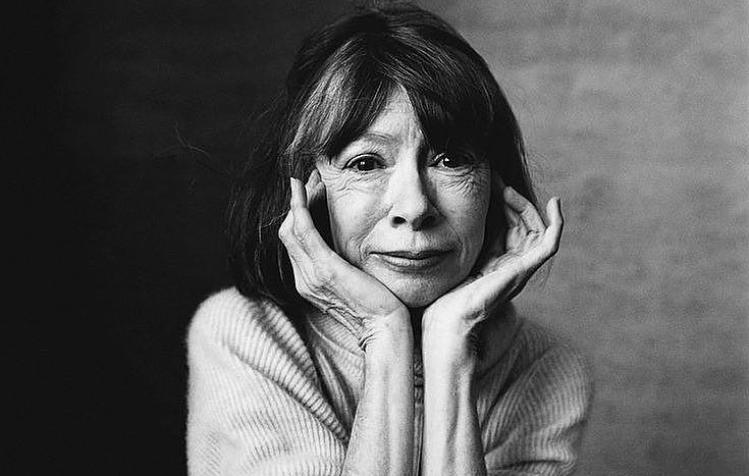

Didion has always been the master storyteller in control of her narrative (critics would say in control of her brand). This creates a problem for the movie director who proposes to turn the camera eye back onto Didion. Her biographer Tracy Daugherty observes that in interviews Didion will offer the same “calculated confessions” even as she writes, “I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind.” This is Didion’s double-edged allure; she’s at once personal and aloof. Any documentary about her must reckon with this challenge: How much can a movie add to the story if Didion has already told us all she thinks we need to know?

Directed by her nephew Griffin Dunne, the documentary Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold is the first Didion has consented to. The ninety-minute film traces her career from her first job writing copy for Vogue (and pitching articles to other magazines, including Commonweal) to her recent memoirs about the deaths of her husband and her daughter. Didion fans can expect plenty of references to her most iconic pieces of writing, but the film never strays outside the narrative Didion has already crafted.

The movie opens with a voiceover of Didion reading from the preface of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, a trope that repeats throughout the film and often substitutes for any biographical heavy-lifting. She summarizes her childhood by reading another line from Slouching: “My first notebook was a Big Five tablet, given to me by my mother.” The full passage in her essay “On Keeping a Notebook” isn’t a bad illustration of her childhood but Dunne assumes we get the reference. Viewers who don’t recognize these quotes are left unmoored. The film moves briskly onward, skipping adolescence in favor of getting to Didion’s writing career as rapidly as possible. Like Athena, Didion springs into the world fully formed, pen and cigarette in hand.

Dunne’s interviews do yield some new information, if not always about Didion herself. For instance, Didion’s editor tells Dunne that when Didion gets writer’s block, she’ll put the manuscript in the freezer. “That’s not a metaphor?” he quips. Dunne interviews literary types like Calvin Trillin and Robert B. Silvers, but he also talks to cultural icons like Anna Wintour and Harrison Ford. (Before his acting career took off, Ford worked as a carpenter and once renovated Didion’s house in Malibu.) And some things about Didion do translate better on film. Despite her world-weary persona on the page, Didion can be very funny on camera. When Dunne asks her why she liked the rock band The Doors, she looks him straight in the eye and says as though it’s obvious: “Bad boys.”

As Didion’s nephew, Dunne has more access to the author than other directors would. But he must tread more delicately. The film captures the often-troubled relationship between Didion and her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, in broad strokes. “You and John were both writing pretty dark stuff then,” Dunne remarks, referring to an episode when John left his wife and young daughter for an extended trip to Vegas. “Well, it was a dark time,” says Didion. The film doesn’t probe further.

Dunne has said that this film “was always going to be a love letter” to his Aunt Joan, and the movie treats its subject with care. Didion may be funnier onscreen but at eighty-two-years old she’s also frailer. When she answers Dunne’s questions, she’ll often wave her arm as she searches haltingly for the right word, as if waiting for the viewer to fill in the blanks. And, usually, we can. We’ve heard this story before.