Janet Malcolm, a frequent contributor to the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, is perhaps best known for her much-contested judgment on the unavoidable duplicity of journalists. Describing how the nonfiction author Joe McGinniss befriended and then betrayed Jeffrey MacDonald, a doctor convicted of murdering his pregnant wife and two young children, Malcolm declared: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness.” Malcolm argued that this provocation was not a condemnation of journalism, but a goad for its practitioners to “feel some compunction about the exploitative character of the journalist-subject relationship.”

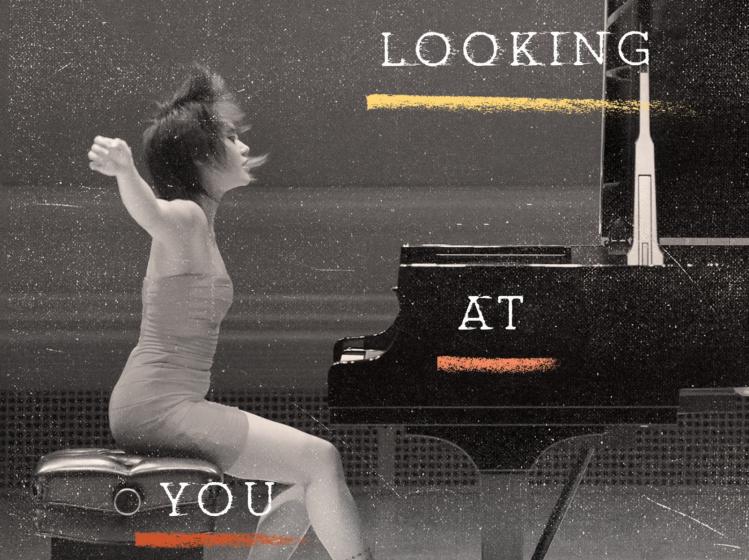

As those sentences make clear, Malcolm is rarely less than a fierce presence on the page, a relentless interrogator (or is it prosecutor?) of the people and subjects she writes about so well. Her new collection of essays, Nobody’s Looking at You, is eclectic: it includes long profiles, reportage, analysis, and book reviews. Among those profiled is Eileen Fisher, the founder of the popular and expensive women’s clothing line. The title of Malcolm’s book is provided by the stern advice concerning pride that Fisher received from her Catholic mother growing up. It was a lesson in humility that fundamentally shaped Fisher’s diffident personality and self-effacing management style. In the essay “Performance Artist,” Malcolm spends a good deal of time with a very different but equally celebrated woman, the brilliant young pianist Yuja Wang. Wang’s flamboyant, short and skintight outfits, “accompanied in all cases by four-inch-high stiletto heels,” have helped to make her a sensation on the classical-concert circuit. The pianist comes across as playful, even endearingly innocent, as well as confident and professionally ambitious. In short, someone determined to have people look at her. The story of Manhattan’s Argosy Bookshop, a family business now run by the three elderly daughters of the shop’s founder, Louis Cohen, is another study of personality and craft. The sisters’ father had miraculously managed to hold on to the store, which sells old and antique books as well as maps and prints, while other small businesses around him fell victim to skyrocketing Manhattan real-estate prices. Anyone who loves books and bookstores will be captivated by Malcolm’s description of the sights, sounds, smells, and charms of the Argosy. “The work of the bookshop is indeed agreeable work,” she writes. “You could even say that it isn’t real work. It has none of the monotony and difficulty and anxiety of work. The cartons of books are like boxes of chocolates. Each book a treat to be savored.”

There are a few less successful pieces in this otherwise strong collection. Malcolm’s usually winning enthusiasm for the idiosyncratic and esoteric doesn’t quite come off in her profile of George Jellinek, the host of The Vocal Scene, a classical music program that ran for many years on New York’s classical-music radio station, WQXR. Jellinek, a Hungarian refugee whose parents were murdered in the Holocaust, led an extraordinary life: fleeing Europe, landing in Cuba, fighting against the Germans with the U.S. Army, and waiting tables in the Catskills before ending up in radio programming. Malcolm herself comes from a Czech refugee family, and she is particularly engaged when writing about New York’s Central European immigrant community. Her parents made a point of mastering English. “The pride that my father and his fellow émigrés took in their ability to stroll through the language as if it were a field of wildflowers from which they could gather choice specimens—of stale standard expressions and faded slang—is touchingly evoked in Jellinek’s radio commentaries,” Malcolm notes.

Malcolm herself is quite at home in that field of wildflowers, and she’s a ruthless pruner of stale and faded language. But she doesn’t communicate the pleasure she derived from Jellinek’s radio program nearly as well as she conveys the enchantment of the Argosy Bookshop, though it’s possible readers with a deeper knowledge and appreciation of classical music may find Jellinek a more engaging personality than I did.

In some ways the most surprising essay in Nobody’s Looking at You is “The Storyteller,” a profile of MSNBC’s popular political commentator Rachel Maddow. Like millions of other liberals, Malcolm seems utterly smitten by Maddow. “Lucid and enthralling,” even “exhilarating,” is how Malcolm describes the TV host’s narrative skills. It is Maddow’s performance of the news as a kind of theater that fascinates Malcolm and garners her admiration. “By reducing the story to its mythic fundamentals, Maddow creates the illusion of completeness that novels and short stories create,” Malcolm writes. “We feel that this is the story as we listen to and watch her.” Others might complain that Maddow can’t stop reducing the stories to their “mythic fundamentals.” Perhaps Maddow is an acquired taste. Her storytelling skills seem labored to me. She is certainly honest, fair-minded, and modest (the daughter of another “very Catholic” mother), but she can also be pedantic and cloyingly theatrical. Malcolm does offer some light criticism of Maddow, but otherwise brings little of her iconoclastic and skeptical temperament to the task at hand.

A 2006 New Yorker piece on Supreme Court nomination hearings, “The Art of Testifying,” is a return to form. John Roberts’s skillful self-presentation is

...like watching one of the radiantly wholesome heroes that Jimmy Stewart, Joel McCrea, and Henry Fonda rendered so incisively in the films of Capra, Lubitsch, and Sturges. They don’t make men like that anymore. But Roberts had all their anachronistic attributes: the grace, charm, and humor of a special American sort in which decency and kindness are heavily implicated, and from which sexuality is entirely absent.

One might say this quip is itself “heavily implicated,” a classic Malcolm deprecation. Roberts’s “invincible pleasantness,” “armor of charm,” and “unsettling language of avoidance” were some of the talents that enabled him to survive the theater of his confirmation hearings virtually unruffled. With a similar feel for the drama of the hearings, Malcolm casts Sen. Dianne Feinstein as “a thirties-movie character in her own right, with her Mary Astor loveliness, and air of just having arrived with a lot of suitcases.” Not many people write with such wit, nor would many have the nerve to describe the presidents of NOW, Planned Parenthood, the Fund for the Feminist Majority, and the executive director of NARAL as “the furies.”

In this collection, Malcolm has very smart things to say about Tolstoy, literary translation, the poet Ted Hughes, and even the reason we tend to use exclamation marks when writing emails! Her remembrance of the revered New Yorker writer Joseph Mitchell is admiring and affectionate but never fawning. Mitchell’s creation of composite characters in his journalism broke one of the cardinal rules of the trade, but Malcolm is not willing to indict him for the crime. “This is not because we are more virtuous than Mitchell,” she writes about nonfiction writers who follow the rules. “It is because we are less gifted than Mitchell…. Reporters don’t invent because they don’t know how to.”

This collection’s most recent essay, which appeared last year in the New York Review of Books, is a review of the republication of Norman Podhoretz’s much-disparaged 1967 memoir, Making It. Podhoretz, the former editor of Commentary, was a prominent literary and cultural critic and an outspoken liberal in his twenties and thirties before joining the neoconservative migration to the right. In her surprisingly positive reassessment of Making It, Malcom quotes novelist, critic, and former Commonweal book editor Wilfrid Sheed’s infamous review as typical of the misguided consensus regarding Podhoretz’s “literary sins.” Sheed clearly found Making It obnoxious, writing that it was a “book of no literary distinction whatever.” But Malcolm is not quite accurate in leaving the impression that Sheed’s objections were principally about the quality of Podhoretz’s writing. To be sure, it was a wickedly dismissive review, but Sheed’s complaints were about Podhoretz’s “vanity,” his “fairly infantile version of success,” and how he “absolutely insists on sharing his vices.” It was Podhoretz’s myopia, his blinding “lack of social observation,” that made the book “flat and unevocative, for want of other actors.”

Malcolm approaches the book in her typically fearless way, trying not to “muddy the waters” by allowing its initial reception and Podhoretz’s subsequent politics to influence her judgment. Fair enough. She is impressed with the author’s candor and the quality of the writing. I have not read the book. Perhaps Sheed was wrong about the literary merits of Making It, but he was undeniably prescient when it came to the character and sensibility of its author, who is now a Trump supporter. “That a man with such an Ayn-Rand-and-water program should call himself a man of the left is symptomatic of the fifties and sixties,” Sheed wrote. Making It unwittingly exposed Podhoretz’s “tastes [as] moving steadily to individual profit, and winding up somewhere to the right of Horatio Alger.”

Reading Janet Malcolm is always a pleasure and a challenge. She’ll make you think twice about people and things you thought you were sure about—people like Norman Podhoretz. When you finish Nobody’s Looking at You, get a copy of The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, Malcolm’s astonishing examination of the difficulties of writing biography and establishing the facts of anyone’s life. There she warns that writing biography and nonfiction journalism is like trying to clean up the house of a hoarder: you are often in the dark, and there is always the danger you will discard what is important only to retain the inconsequential. Lives are inherently messy, complicated, and contradictory. “The goal is to make a space where a few ideas and images and feelings may be so arranged that a reader will want to linger awhile among them, rather than to flee,” Malcolm explains. Few writers are as good at making us linger, while at the same time cautioning us about the inherent limitations and deceptions of storytelling.

Nobody’s Looking at You: Essays

Janet Malcolm

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $27, 304 pp.