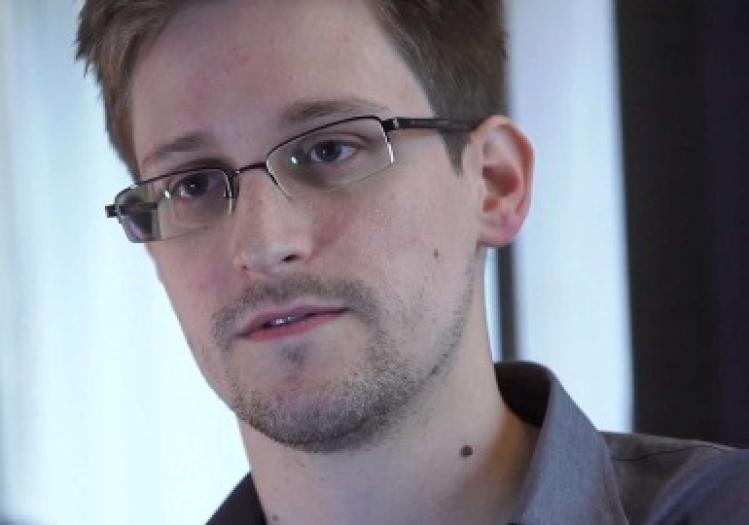

Edward J. Snowden, the thirty-year-old former National Security Agency contractor who handed over a treasure trove of classified documents about U.S. government surveillance to the Washington Post and Britain’s Guardian, is a hero to some and a traitor to others. He claims to have acted out of a sense of outrage over the NSA’s indiscriminate collection of the phone and internet records of Americans, decrying the danger such intrusive government oversight poses to democracy and privacy. Snowden subsequently fled to Hong Kong, and from there to Moscow. His eventual destination appears to be Ecuador, Cuba, or Venezuela.

Snowden’s efforts to elude U.S. authorities cast an ambiguous light on his motives; the countries where he has sought refuge are not known for upholding the sort of democratic values he claims to be defending. While demanding accountability from the U.S. government, he appears to be seeking immunity for his own actions. Snowden’s purposes and fate, however, should be of secondary concern. However misguided his actions may have been, they have reopened a much-needed debate about the reach and authority of what is often called the National Security State. While defending the NSA programs, even President Barack Obama seems to welcome that debate. “You can’t have 100 percent security and also then have 100 percent privacy and zero inconvenience,” Obama noted when asked about Snowden’s leaks. “We’re going to have to make some choices as a society.... There are trade-offs involved.”

Administration officials and members of Congress say the government’s extensive surveillance programs are crucial to preventing terrorist attacks, and that Snowden has done real damage to efforts to keep Americans safe. Because almost all the relevant information remains classified, it is difficult to assess that claim. NSA officials have now promised to make public details of some of the dozens of terrorist plots they say the massive data-collection effort, called Prism, has helped thwart. That sort of disclosure is long overdue. Although Prism was approved by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court and is monitored by the intelligence committees of Congress, many Americans were shocked to learn that the government now stores their phone and internet records for possible use in future investigations. While the government is prohibited from listening to the tracked calls, it uses sophisticated algorithms to trace calling patterns. If a series of related calls seems suspicious, the NSA or FBI then gets a warrant from the FISA court to investigate further. No abuse of those procedures has come to light. Still, the mere existence of such records in the government’s hands, information that might easily be exploited for political purposes, should concern every American.

It is axiomatic that fighting clandestine terrorist groups requires clandestine methods. Sources and allies must be protected; in preemptive actions the element of surprise must be preserved. Secrets about ongoing investigations cannot be compromised without jeopardizing counterterrorism efforts. It is harder to justify keeping such details secret after the fact. Judgments about the trade-offs between privacy and safety cannot be made unless the American people know what the government has done in our name. Even if everything the government does to combat terrorism is technically legal, not everything legal is prudent, wise, or morally justified.

As a nation, we rely on a system of checks and balances to prevent an excessive concentration of state power. Those checks and balances are strained to the breaking point during times of war, and especially during a war as ill-defined and open-ended as the fight against terrorism. Congress is notoriously pusillanimous when it comes to national-security issues. The courts, meanwhile, are loath to intervene, preferring to leave the conduct of “war” to the other two branches. The executive rarely passes up an opportunity to expand its war-making powers. The result is the steady accumulation of influence by the nation’s security agencies. As political philosopher and former Clinton administration official William A. Galston recently observed, “It may be true that as currently staffed and administered, the new institutions of surveillance do not threaten our liberties. It is also true that in the wrong hands, they would make it much easier to do so.”

Devising checks and balances that will reduce that threat should be a goal that unites all Americans. Given the complexity of the issues, perhaps a first step would be to convene a truly credible bipartisan study commission. Bring together representatives from the legislative, executive, judicial, military, and security branches, as well as members of the fourth estate. The commission’s mandate should be to inform the American people about the hard choices we face. The trade-offs between liberty and security should not remain a secret any longer.