2016 was a fabulous year.

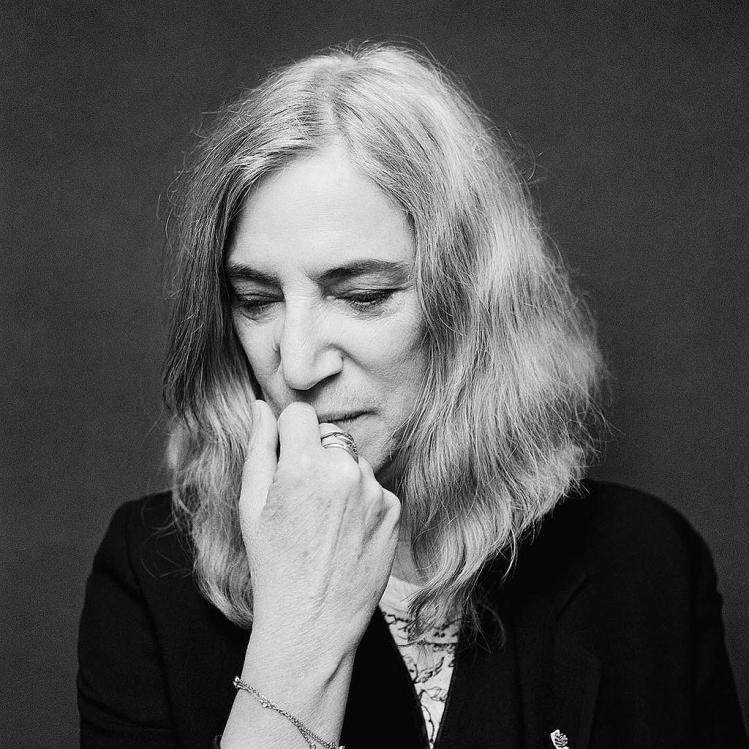

I’m using “fabulous” in the archaic sense of “known through fable.” Fabula, the Latinate root, suggests the storied situations, monsters, magical animals, and objects of folklore. Often, in fables, someone puts a curse on someone else, and the one who lifts the curse is the one who can spy the treasure in detritus, the boon in rough-hewn, hidden things. In Year of the Monkey, Patti Smith—poet, award-winning memoirist, rock icon—is that curse-lifter, the boon-provider, descrying a sea of possibilities in 2016’s bellicose actors, its swift and seemingly irrevocable changes.

The book unfolds over the course of twelve months like a long, chaptered prose poem. Its main touchstone—there are a few—is the death, on July 26, 2016, of Smith’s friend of four decades, Sandy Pearlman. Pearlman was, among many things, the founder, manager, co-producer, and songwriter of the band Blue Öyster Cult, as well as an early influence on Smith. When Year of the Monkey opens, on January 1, 2016, Smith is staying at the Dream Motel in Santa Cruz, desperate for a coffee that never materializes (coffee is another touchstone, as is the Dream Motel’s sign which, per fabulist mode, speaks to her throughout the book). Her band had played a run of shows at the Fillmore in San Francisco, culminating with a New Year’s Eve concert. Pearlman was supposed to meet her there, then return with her to Santa Cruz. But on New Year’s Day, two days after her sixty-ninth birthday, Smith and another longtime confrere Lenny Kaye find themselves in Pearlman’s Marin County hospital room, where he was taken after having a cerebral hemorrhage on the eve of their first show.

Pearlman’s absence and eventual departure is not the only loss Smith meditates upon. Their friendship connects her to former paramour Sam Shepard who, in 2016, was already suffering the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) that would take his life on July 27 the following year:

[Pearlman’s] suggestion that I should front a rock band seemed pretty far-fetched. At the time, I was seeing Sam Shepard and I told him what Sandy had said. He didn’t find it extreme at all. He looked me in the eye and told me I could do anything. We were all young then, and that was the general idea. That we could do anything.

That “anything” has been a motif in Smith’s work from her earliest verse collections (Seventh Heaven, in 1972, and Wītt, in 1973), through her song lyrics to her memoirs. Her imagination has never brooked limitation. Contained in her poems are multitudes and wonders: a glass box in which a boy holds a storm captive, a little girl with a desert in her cheek, Jeanne d’Arc fantasizing about sex with her captors, the “last metallic moments” of the TV show Dragnet, the Queen of Sheba’s daughter bathing with a leper. In Year of the Monkey, even as life becomes more attenuated by death and uncertainty, there is still hope, sourced in imagination. In the epilogue, Smith writes:

A lot of rough things happened, begetting things even more terrible…. [T]he ravaging of Puerto Rico. The massacre of schoolchildren. The disparaging words and actions against our immigrants…. Sam is dead. My brother is dead. My mother is dead. My father is dead. My husband is dead…. Yet I still keep thinking that something wonderful is about to happen.

That kind of hope has always come from Smith’s unwavering faith—expressed in all her work—in the power of art to teach and heal, to give value to suffering. In the chapter “The Mystic Lamb,” Smith tells of traveling, just after her seventieth birthday, to visit Shepard in a town near Santa Ana, carrying with her a small, illustrated book on the Ghent Altarpiece:

The magnificent polyptych was painted on oak in the fifteenth century by the Flemish brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck. The whole of the altarpiece was committed with such supple eloquence that it was venerated by all who beheld it and believed by many to be a conduit to the Holy Spirit…. Once I touched the surface of the exterior panel and was filled with awe, not in the religious sense, but for the artists who realized it, sensing their turbulent spirits and their majestic concentrative calm.

For Smith, turbulence of spirit is the mark of a great artist. It is also related to hope and faith because, ultimately, it leads to charity, the ability to join one’s suffering with that of others to communicate value, to provide the boon. In the chapter “The Holy See,” which begins with the Day of the Dead and takes us through the election to Christmas and the author’s seventieth birthday on December 31, Smith drops in the incredible statement, “Our quiet rage gives us wings, the possibility to negotiate the gears winding backwards, uniting all time.” Reading that, I was reminded that Smith has always known the artus point where darkness becomes light. In “Sister Morphine,” which appeared in her 1978 poetry collection Babel, she wrote:

only by dwelling in the pit can you create

to be delivered is to be raised.

the creator is delivered

determined he rises

thus it is that pain gives man wings

And in “Babelogue,” from her album Easter: “Those who have suffered understand suffering and thereby extend their hand.”

While Year of the Monkey advances chronologically, with time stamps (“Back home, in the center of February...” or “On the first day of spring I shook out the featherbed...”), kairos time always gently interpolates chronos. In “A Circle of Quiet,” the second volume of The Crosswicks Journals, Madeleine l’Engle reminds us that “the Greeks were wiser than we are. They had two words for time: chronos and kairos. Kairos is not measurable. Kairos is ontological. In kairos we are, we are fully in isness...”

Every moment in Year of the Monkey is kairos. Smith observes, “Marcus Aurelius asks us to note the passing of time with open eyes.” This, for me, is the underpinning of her year-long reportage: to act in accordance with her own imperative, to “submit and observe and take notice” (also from “Sister Morphine”). It’s what poets have always done best.

There’s a Russian fable called “The Tale of the Little Goat Shedding On One Side.” A peasant takes pity on a mangy goat and sets it up in his shed. The ungrateful (but magical) animal runs from the shed to the house and locks everybody out. The peasant’s pet rabbit inveigles a rooster and a wolf to force the goat to unlock the door, but the goat refuses each, bellowing, “If I come out, I’ll break all your ribs.” A bee volunteers to fly in through a window and sting the goat. The ruminant finally runs out, the rabbit enters, eats, drinks, and lies down to sleep. “And when he awakens,” the fable concludes, in the black-humorous fashion of Russian folk stories, “the real tale will begin.”

I have the uncomfortable feeling that the real tale has only just begun. If something still more fabulous lies ahead, Smith is the guide—the artist, the boon-provider—we’ll need.

Year of the Monkey

Patti Smith

Knopf, $24.95, 192 pp.