A few months after the terror attacks of 9/11, the New Yorker ran a cover imagining New York’s boroughs as Middle Eastern provinces. A section of Queens was dubbed “HipHoppaBad,” while part of Brooklyn was rechristened “Fuhgeddabouditstan.” And all the way to the south, toward the bottom of the cover, was the borough of Staten Island—redubbed “Stan.” Which pretty much captures the way many still think of New York’s fifth borough, if they think of it at all: not quite a part of things, a distant working-class wasteland of sports bars and tanning salons.

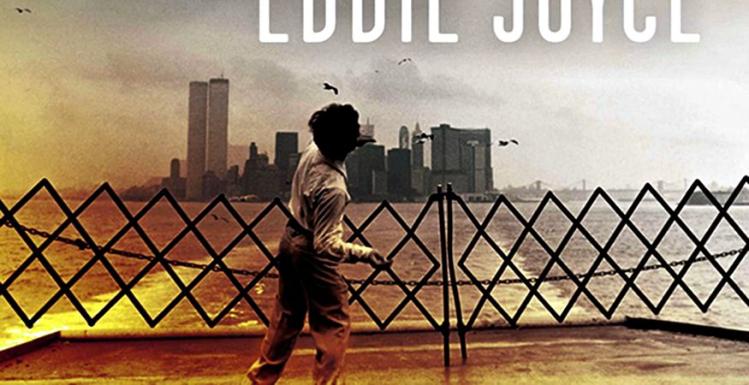

The inherent difficulty of telling a compelling story about a place like Staten Island (or South Boston or Buffalo or Providence, to name just a few similar enclaves) is the temptation to rely on satire or sentimentality. Only a handful of gifted writers—Richard Russo, Alice McDermott, among them—have managed to conjure from such seemingly modest landscapes fully realized characters, rather than mere saints or sinners. On the evidence of his novel Small Mercies, Eddie Joyce can be added to the list.

Joyce is a Harvard and Georgetown grad who quit practicing law in 2009 to help raise his twin daughters and pursue “his dream of being a writer,” as his book jacket puts it. Small Mercies traces the effect of 9/11 on the people living in what one character calls “the servants’ quarters of New York.” These are the teachers and firefighters, the cops and sanitation workers, “the occasional accountant or lawyer thrown in; Italian or Irish or maybe something else but not likely.”

Joyce’s novel charts a single week in the lives of the Amendola family, headed by the grieving Gail—a Brooklyn Irish-American—and her husband Michael, whose external cheeriness masks a brooding streak rooted in a conflict with his Italian immigrant father. In brief, effective flashbacks, Joyce captures the terrible moments when neighbors gathered and Gail and Michael—along with the entire world—learned about the planes hitting the towers. The Amendolas’ firefighter son Bobby was working that day. “They cry, hope, pray.... The ghost light of the television plays the same images over and over. They cannot watch. They must watch.”

Small Mercies is ultimately concerned with family ties and the emotional impact of Bobby’s death on his wife and child, his parents, and his two brothers: Peter, “the golden boy,” who fled Staten Island and became a wealthy lawyer, and Franky, who fled to the bottom of a bottle, becoming “a drunken, ruined memorial to his dead brother.” Joyce presents the Amendola family in full, their hard-bitten wisdom earned not only through tragedy but through the daily grind of life.

Joyce is particularly strong on the existential quandaries of parenting. As a new mother, Gail—in touching flashbacks with her mother-in-law—learns that “caring for an infant requires the energy of the young and the patience of the old.” With grown children, retired-firefighter Michael laments: “He thought fatherhood would be like his job: you put in your twenty.... But it doesn’t end. Not until you’re in the ground.” In the end, everyone must contend with the fact that “the days are long but the years fly by.”

For such a thoroughly Catholic culture, the presence of the church in Small Mercies is conveyed largely through mundane rituals (“They order a pie, usually pepperoni but plain last night for Lent.”), which may well say just as much about the state of northeastern Catholicism as it does about the veracity of Joyce’s realism. The novel also spends a bit too much time chronicling the cancellation of a legendary college basketball betting pool. Also, though it’s easy to sympathize with the struggles of striving Peter, they occasionally come off as clichéd, like outtakes from a movie script by Ed Burns. Sentimentality shows itself from time to time, mainly in the form of Joyce’s obvious affection for his characters, but he cannot be accused of ignoring a certain kind of political narrow-mindedness not uncommon on (or unique to) Staten Island. The parochialism is represented most vividly by Franky, who is angry, delusional, and, thus, unpredictable—which might actually leave some readers wanting more of him.

While Joyce delivers a touching portrait of a fascinating place, Small Mercies also achieves something of significance on the socio-historic level. Roughly 10 percent of 9/11’s victims were from Staten Island—those cops and firefighters and secretaries who keep the city going. Decent yet unassuming jobs that will neither make you rich nor leave you poor, and which are readily available to second- and third-generation Americans who remain—in ways they themselves might choose not to acknowledge—proudly unassimilated. It is thus fitting that Joyce’s story is set on an island stuck between the gleaming metropolis and the rest of the country. And it’s about time that the borough has inspired a writer so capable of capturing its special character.