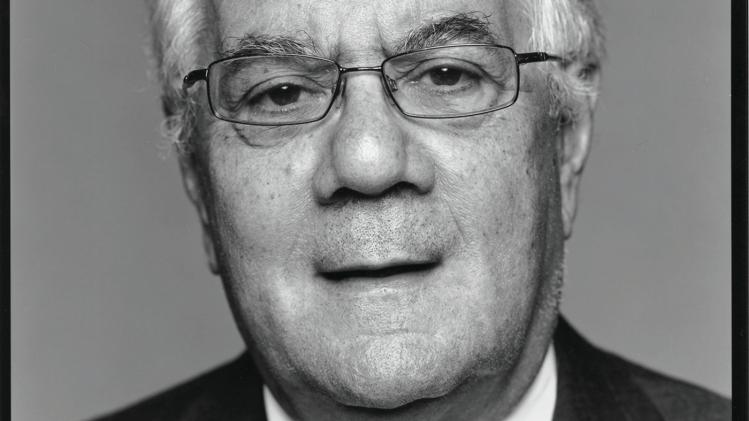

Barney Frank was born to be a politician. He never turned down a chance to work on a campaign (Adlai Stevenson, in 1956, at age sixteen), serve as troubleshooter (for Boston Mayor Kevin White), run for state office (Commonwealth of Massachusetts), and jump in, on fifty-two hours’ notice, to run for the House seat of Robert Drinan, SJ, who had been instructed by John Paul II to drop out of his 1980 reelection campaign.

Representatives in the U.S. House require a variety of skills. Being agreeable doesn’t need to be among them; being smart, funny, abrasive, and even obnoxious will suffice. That’s one lesson I draw from Frank’s account of his sixteen terms in Congress (1981–2013). His self-described non-linear thinking goes along with his propensity for fast-talking, impulsive acts, cajoling, and its dark side, bullying. He is also by his own testimony a counter-puncher, quick on his feet, with his smarts and good memory made for the give and take of debate and repartee rather than giving speeches.

He began life in Bayonne, New Jersey, and early on declared himself a New Deal liberal. To the modern Democratic Party’s traditional socioeconomic causes—the poor, the elderly, working people, renters (over home-buyers), and civil rights—Frank added all the liberal issues, especially abortion and gay rights, that have eroded the party’s once large majority. Harvard College followed by Harvard Law School brought him to the most liberal state in the union, which may explain his long political tenure. Despite the decennial redrawing of congressional districts, Massachusetts politicians continued to back him either because he couldn’t lose (his conclusion), or because if he did lose they would have been happy to see him go (his hint).

When delving into the intricacies of passing legislation, organizing committee hearings, arm-twisting votes, and rallying the troops, Frank is not big on chronology or details. Hard to tell at times: Are we in the Jimmy Carter or the G. H. W. Bush administration? Is this the run-up to the 1991 Gulf War or the 2003 invasion of Iraq? Despite such inexactitude, the “inside politicking” stories of a long-serving member of the House both inform and amuse.

Frank recognized early in the Reagan administration that the supply-side theory of tax cuts was not just red meat to the Republican constituency. The Republican claim that reducing taxes would not shrink government revenues was of course a device to shrink those revenues and thereby reduce the size of government. It was, according to Frank, a “politically potent two-step—delegitimizing government while defunding it.” But “starving the beast,” he argues, was not just a Republican gambit. Bill Clinton diverted budget surpluses to reduce the deficit rather than fund government programs. Frank fought back against Clinton as well as the Republicans as the programs he most cared about were being starved.

Frank claims that it is this pattern of increasingly ineffective government plus a dysfunctional economy that has driven the white working class away from the Democrats. He gives little weight to the culture wars, but then he has been at their vortex, defending abortion rights and implementing gay rights. Even before exiting the closet himself, he carried the banner in Congress of the LGBT movement, albeit somewhat before those initials came together.

As the economy melted down during the 2008 presidential election, the combination of Frank’s brains and his power as chair of the House Financial Services Committee probably saved the country from another Great Depression. He was acutely alert to the financial and political issues at stake, and knew that Republicans in the House were unlikely to cooperate in any bailout. Instead he turned to Bush administration officials, Henry Paulson and Sheila Bair, as well as Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke. Together they crafted a plan (TARP) that was eventually implemented by the Obama administration. Frank and Senator Christopher Dodd (D-Conn.) then engineered the return of regulatory controls on major financial institutions. Frank’s knowledge of the freewheeling, imaginative, and ultimately destructive operations of Wall Street suggests he might have done well as a hedge-fund manager himself. The nation was lucky to have him in government during the crisis. As the economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman has argued, if Dodd-Frank legislation didn’t solve all our banking problems it at least solved some of them.

Frank has rules for political effectiveness, which could be reissued as “Chairman Frank’s Little Red Book.” Some are anodyne: “Ideologically and emotionally driven choice of direct action over less dramatic political activity is often counterproductive.” (Given his stories, they always seem counterproductive.) A bon mot sums up his political philosophy: “There is a price to pay for rejecting the partial victories that are typically achieved through political activity.” Allies on the left seemed to him shortsighted in underestimating what legislators can do to advance their cause. Opponents on the right are often more acute at reading public opinion and better at pressuring Congress. Their weakness, however, is for relitigating decided issues (for example, the Affordable Care Act) and creating gridlock in Congress.

Despite Frank’s often bombastic persona, he is at heart an incrementalist. He can be critical of both the left and the right. He also believes that when it comes to legislation a politician must keep his promises. He attributes his longevity in office to providing strong constituent services (think New Bedford fishermen), cooperation with congressional leaders, especially Tip O’Neill and Nancy Pelosi, mastery of House rules, and his influential committee assignments. Mindful of the role chance plays in politics, he attributes his good luck in winning his first congressional seat to a man he never met, John Paul II. The irony of the outcome is not lost on him, nor was it lost on Fr. Drinan, who later wondered whether the pope “was happy with the way that decision worked out.”