“It would seem,” Darryl Pinckney writes in the second of the two essays in this volume, “that although black people are in the mainstream, black history still isn’t, because certain basic things about the history of being black in America—American history—have to be explained again and again.” That sentence—on page seventy-six of the ninety-nine-page text—appeared just as I found myself wondering impatiently: Why is this fellow taking up so much of my time telling me stuff I already know?

The reason is that these essays are aimed not at folks like me, a black man who has studied African-American history in some depth and, at age sixty-seven, has lived through a considerable part of it. Rather, they are aimed at white people, like those who attend lectures at the New York Public Library, where the talk on which the first essay is based was delivered in 2012, or those who read the New York Review of Books, where the second essay first appeared.

White people enjoy the luxury of caring—or not—about the history of being black in America. And because so many of them so often opt not to care, “certain basic things…have to be explained again and again.” Things like Reconstruction, that all-too-brief flowering of black political freedom that followed the Civil War and was crushed through Ku Klux Klan terrorism; through crude political machinations like the Hayes-Tilden Compromise, grandfather clauses and white primaries; and, finally, through the benediction of the United States Supreme Court on the odious practice of “separate but equal” in its infamous decision in Plessy v. Ferguson.

The first essay, from which the book’s title is derived, is a meditation on how we got to where we are now, with a largely unified black vote constituting a key bloc of the Democratic coalition, but threatened by this era’s equivalent of the Hayes-Tilden Compromise: the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling in Shelby County v. Holder, striking down the provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 requiring preclearance of local election-rule changes by the Justice Department.

Besides being a breathtaking act of judicial activism, Pinckney says, Chief Justice John Roberts’s majority opinion in Shelby County was naïve and ahistorical. It disregarded the history of efforts in the South to diminish black voting power—efforts that continue to this day with devices such as voter identification laws—and so failed to appreciate the unregenerate nature of those who seek to perpetuate white political control and suppress black voting power. In Pinckney’s view, the conditions that gave rise to the Voting Rights Act in 1965 still exist today in the form of what dissenting Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg called “second-generation barriers,” and they still require a vigorous federal remedy.

It is difficult to discern what significance Pinckney attaches to the election—twice—of Barack Obama as president of the United States. Was it confirmation that blacks—like the Irish, the Mexicans, the Jews, the Italians, the Poles and others—had finally attained to the coveted American status of acceptance, of…whiteness? “There are,” he says, “some white people who would rather see the country wrecked than have anything work under President Obama. It is a shock that racism in U.S. political life is so virulent that the heirs of white supremacy, unwilling to face the prophecy in the demographics, would rather destroy it all than hand it over.” But those white people lost—at least in 2008 and 2012, although they seem to be winning now through their rearguard resistance. In the end, Pinckney seems to suggest, all that black people can do is keep on keeping on. Invoking the memory of his parents and other family members staffing voter-registration campaigns, he says, “I vow to keep alive in my heart their defiance and hope. It is the best way for me to honor their memory, their local, brave actions, that state of grace the committed can become acquainted with.”

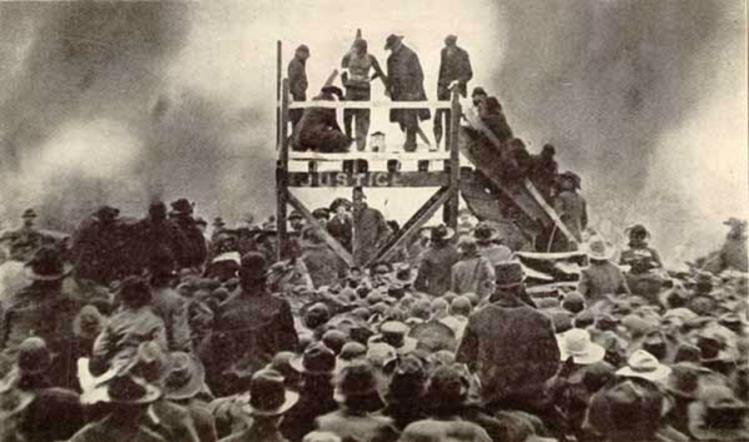

The second of Pinckney’s essays, “What Black Means Now,” is really only a piece of an essay that appeared in the May 24, 2012, issue of the New York Review of Books. It is not explained why the piece was truncated. What it mainly achieves is to introduce white readers to some of the new Obama-era generation of blacks writing on race—Zadie Smith, Eugene Robinson, and Touré. It is not at all clear what Pinckney intended to convey by the anecdote—an account of the lynching of a cousin in 1930—with which the essay abruptly and mysteriously ends.