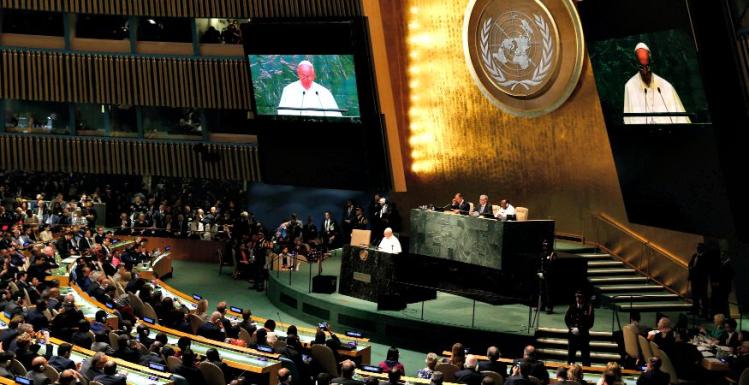

In a sprawling forty-five-minute address to the United Nations this morning, Pope Francis again urged world leaders to take practical measures to protect the environment, avoid armed conflict, and protect the most vulnerable.

After “reaffirming the importance” of the UN in working to promote justice and human rights,” the pope prodded the assembly to pay attention to the “victims of power badly exercised”: the environment and the “ranks of the excluded.” He warned against “false rights” presented by “the world”—and then he asserted a new one: “a true ‘right of the environment’ [derecho del ambiente, in the original Spanish] does exist,” Francis said. That is a very big deal.

Before the publication of Laudato si’, there had been some speculation about whether the encyclical would speak of the environment itself as having rights. After Francis told journalists that human beings had lorded their power over nature Robin Darling Young asked:

Was he really implying that created nature—the environment—has rights of its own? Such a view on the part of the pope would be a significant development in Catholic thinking about the inherent worth of creation apart from the humans who dominate it. We shall soon find out if he meant it.

It sounds like he did.

While the pope did not expand on this idea, he did connect it to the rights of men and women. There is a “right of the environment” because “we human beings are part of the environment.” We live “in communion with” the environment, “since the environment itself entails ethical limits which human activity must acknowledge and respect.” Harm the environment and you harm humanity. Members of the monotheistic religions, Francis said, believe that humanity “is not authorized to abuse [the planet], much less to destroy it.” And all religions view the environment as “a fundamental good.”

Francis again linked environmental abuse with “a relentless process of exclusion”:

Economic and social exclusion is a complete denial of human fraternity and a grave offense against human rights and the environment. The poorest are those who suffer most from such offenses, for three serious reasons: they are cast off by society, forced to live off what is discarded and suffer unjustly from the abuse of the environment. They are part of today’s widespread and quietly growing “culture of waste.”

Francis endorsed the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development as “an important sign of hope,” and predicted that this year’s Paris climate-change conference will “secure fundamental and effective agreements.” Yet agreements, while “necessary steps toward solutions,” are not enough, the pope said. True justice requires a constant act of will—a will that is not satisfied with declarations, announcements of agreement. No, justice requires governments to take concrete steps to address environmental degradation and economic exclusion “as soon as possible.”

It must never be forgotten that political and economic activity is only effective when it is understood as a prudential activity, guided by a perennial concept of justice and constantly conscious of the fact that, above and beyond our plans and programs, we are dealing with real men and women who live, struggle and suffer, and are often forced to live in great poverty, deprived of all rights.

Recalling his barnburner in Bolivia, Francis reminded the UN what rights he wants secured. “In practical terms, this absolute minimum has three names: lodging, labor, and land; and one spiritual name: spiritual freedom, which includes religious freedom, the right to education and other civil rights.”

The ecological crisis, “the baneful consequences of an irresponsible mismanagement of the global economy,” threatens the very existence of humanity, Francis said. This calls us to reflect on why we are at all, and whom we are for. We must “recognize a moral law written into human nature itself, one which includes the natural difference between man and, and absolute respect for life in all its stages and dimensions.”

“War is the negation of all rights and a dramatic assault on the environment,” Francis declared. Over the course of the UN’s seventy years of existence, and especially during the first fifteen years of this millennium, we have seen how the rule of law, of international norms, has been used and abused. When the UN charter is “applied with transparency and sincerity,” the results will be peaceful. But when international norms are flouted, or used when expedient and ignored when not, “a true Pandora’s Box is opened.” He did not speak the word Iraq. The UN charter is designed for peace, for “friendly relations between nations.” Yet we see “the constant tendency toward the proliferation of arms, especially weapons of mass destruction, such as nuclear weapons.” Francis also rejected the logic of nuclear deterrence: “An ethics and a law based on the threat of mutual destruction—and possibly the destruction of all mankind—are self-contradictory and an affront to the entire framework of the United Nations, which would end up as ‘nations united by fear and distrust.’” Nuclear weapons must be eliminated, not stockpiled. Francis also signaled his support for the recent nuclear agreement with Iran as “proof of the potential of political good will and of law, exercised with sincerity, patience and constancy.”

Where international cooperation is missing, crises flourish. In the Middle East and Africa,

Christians, together with other cultural or ethnic groups, and even members of the majority religion who have no desire to be caught up in hatred and folly, have been forced to witness the destruction of their places of worship, their cultural and religious heritage, their houses and property, and have faced the alternative either of fleeing or of paying for their adhesion to good and to peace by their own lives, or by enslavement.

Wherever such conflict arises, Francis said, we must hold people above partisanship.

In wars and conflicts there are individual persons, our brothers and sisters, men and women, young and old, boys and girls who weep, suffer and die. Human beings who are easily discarded when our only response is to draw up lists of problems, strategies and disagreements.

But not all wars are waged with armies. Francis also highlighted the perils of the drug trade, which includes human trafficking, money laundering, and child exploitation. This corruption, according to the pope, has “penetrated” all levels of life, from the artistic to the religious to the political, and has “given rise to a parallel structure which threatens the credibility of our institutions.”

In conclusion, Pope Francis wove the various threads of his expansive address into a consistent ethic of care for all creation:

The common home of all men and women must continue to rise on the foundations of a right understanding of universal fraternity and respect for the sacredness of every human life, of every man and every woman, the poor, the elderly, children, the infirm, the unborn, the unemployed, the abandoned, those considered disposable because they are only considered as part of a statistic.

Echoing his important claim of “a right of the environment,” Pope Francis reminded the United Nations that the earth, our “common home…must also be built on the understanding of a certain sacredness of created nature.”