Vatican officials have begun efforts to publicly defend next autumn’s controversial canonization of Junípero Serra, the Franciscan friar who established the California Missions in the mid-to-late 18th century. Pope Francis will declare the Spanish-born missionary a saint on September 23 in Washington, D.C. But Historians, and even some contemporary members of Serra’s own religious order, have questioned whether the evangelization methods he used among the native Indians were very “Christian.” Scholars and today’s Franciscans will likely continue to debate for a long time whether or not Fr. Serra was excessively cruel and ruthless by using physical punishment to bring “heathens” (his very words) to Christ. But Guzmán Carriquiry, secretary of the Vice-Presidency of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, implied that criticism on such grounds amounted to nothing less than hypocrisy. “Corporal punishment is still legal in the United States and even examples of torture emerge from time to time,” the Uruguayan pointed out on Monday at a Vatican press conference. In his prepared remarks, as well as in answers to reporters’ questions, he seemed to suggest that criticism of Serra was also being used as a smoke screen to hide the longstanding “anti-Hispanic and anti-Catholic prejudice” that continues to linger among white Americans. “[His canonization] will allow many millions of Hispanics in the United States to free themselves from a mentality that they are a foreign people on the margins of society, just barely tolerated and often discriminated,” he said. Mr. Carriquiry stressed that the canonization would also balance a one-sided and erroneous historical account that the United States was “discovered” by English Protestants who arrived on the Mayflower. He claimed that “within five years, Hispanics will make up half the Catholic population” in the United States and suggested that the canonization of Junípero Serra would help the American Church “consider [this] more profoundly.”

****

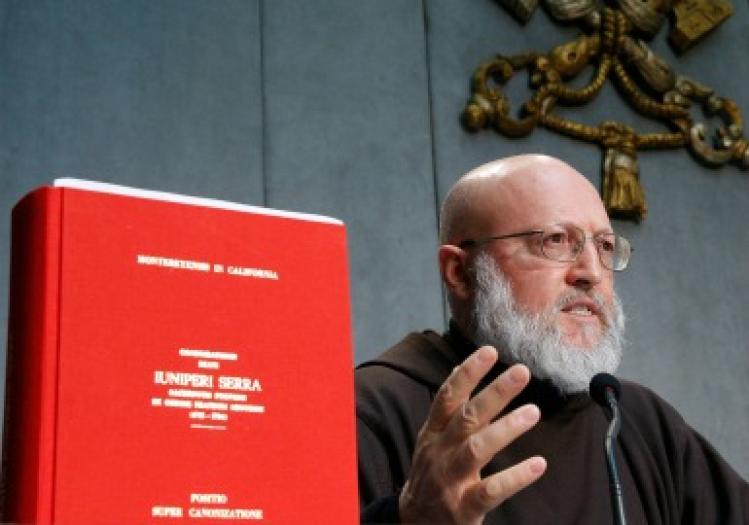

Part of Monday’s briefing at the Holy See Press Hall was aimed at unveiling a symposium on the soon-be-declared Franciscan saint, which will be held the morning of May 2 at the Pontifical North American College (NAC), the U.S.-run seminary in Rome. Among the speakers will be the promoter of Fr. Serra’s sainthood cause, Guzmán Carriquiry, the head of the Knights of Columbus (Carl Anderson), Cardinal Marc Ouellet (president of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America) and Los Angeles’ Mexican-born Archbishop José Gómez. But the main feature that everyone’s talking about will be a concluding mid-day Mass presided over by Pope Francis. Believe it or not, after two full years as Bishop of Rome, this will be the very first time that he steps foot into one of the many national seminaries in the Eternal City. He has not even visited any of the three major seminaries of his own diocese. He was supposed to go the Seminario Romano Maggiore in February 2014, but cancelled at the last minute due to a slight fever. Pope Francis has never rescheduled, not even to mark the institution’s 450th anniversary, which took place a couple of month’s ago. So a papal visit to NAC is a big, big deal. The United States bishops founded the college in 1859, two years after establishing its first seminary abroad in the Belgian university town of Louvain. Alas, they closed the seminary in Louvain at the end of the 2010-2011 academic year, basically because the increasingly conservative hierarchs did not want their future priests studying at a university they considered too progressive and overly critical of the magisterium. In marked contrast, they have flooded the NAC with a record number of students and tons of money from wealthy donors. The seminarians tend to be more traditional, mostly having entered into formation during the previous pontificate. It is no secret that many of them would be inclined to emulate John Paul II or Benedict XVI over Pope Francis. Perhaps, the papal visit is meant, in part, to help them reconsider.

****

It only took three years, but Bishop Robert Finn is finally gone. Three years after he became the first bishop in the United States to be convicted of a misdemeanor for failing to report suspected sexual abuse of a minor. The Vatican announced on Tuesday that the 62-year-old prelate had “resigned.” But the entire world knows he was forced to do so by the Congregation for Bishops—under specific instructions of the Pope. The move has raised all sorts of hopes among Catholics in other dioceses who would like to see their bishops removed, too. But in most cases their hopes are probably in vain. Popes—especially Francis—do not like to be pressured by public opinion to make decisions, especially when it comes to high-level personnel matters. They are especially slow to remove a bishop because of protests. It sets a dangerous precedent. John Paul II actually forced Cardinal Bernard Law to remain as Archbishop of Boston, certainly longer than the cardinal would have preferred. When Vatican officials finally realized that he could not move an inch without being mobbed by reporters and protesters; when they understood that he was totally hampered from physically governing or pastoring the archdiocese; then, and only then, did they allow him to resign. It is possible that the same fate that befell Cardinal Law and Bishop Finn will also be visited upon Bishop Juan Barros of Chile. Similar to the cardinal, he’s finding it difficult to go unmolested in public and must rely on bodyguards to keep angry protesters at bay. But don’t expect to see many other mitered heads to fall. Catholics in San Francisco who don’t like Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone and those in St Paul and Minneapolis who are fed up with Archbishop John Nienstedt probably should not hold their breath. There are not enough papal basilicas in Rome or other insignificant posts in the Vatican where the Pope can park them.