In view of the fact that all workers in the New York House of Hospitality live on Mott Street instead of in scattered homes as they do in our other centers where there are only one or two in charge, it may seem that there are many to do the work in New York. But our staff is not so large. Peter Maurin and I are traveling and speaking a great deal, and I have a large correspondence and much writing to do besides the monthly paper to edit. William Callahan has been managing editor for the past two years, but he also has to travel and speak, besides handling details of management. Edward Priest has been forced to live away from the work the past year and a half and can give little time to it. John Curran handles correspondence and travels; Ade Bethune lives in Newport and works there. Other members of the staff whose names do not appear on the masthead are similarly occupied. John Cort has his time taken up completely by the Association of Catholic Trade Unionists; Tim O’Brien by the Catholic Union of Unemployed; Pat Whalen and Martin Flynn help John Cort; which leaves at present only Joe Zarella in the office with Julia Parcell giving her afternoons. Cy Echele and Herb Welch help with the coffee line in the morning, which means four hours’ work, and then sell papers on the streets all afternoon. This street apostolate is of great importance. Other members of the group are on the farming commune.

The young men take turns on the line every morning so that usually each one is called upon just two mornings a week. (It is an interesting fact that these works of mercy are carried on by young men throughout the country. Young women are either occupied with their families or prospective families so that other aid must come from them. Then, too, much of our work, dealing in general with masses of men, is unsuitable for women.)

New York has more than its share of visitors so we have many guests who are interested in the work and in the social ideas of Peter Maurin. Often we have visitors from early morning until late at night, coming to every meal and remaining for discussions which go on at all times of the day, when two or three are gathered together. (I recall one such discussion when last summer three young priests met for the first time at the Catholic Worker—one from California, one from Texas, and one from New York—and have been fast friends ever since. They spent the entire afternoon with us and stayed to supper.)

Because of the crowds of callers and visitors for one or two weeks’ stay, it is harder to get all the work done sometimes than if we had just two or three running the place. More people means more work, as every woman knows. The fewer there are, the less there is to do. The fewer there are running one particular work, the more gets done very often. Witness a clumsy committee of thirty as compared to a committee of three.

Other groups contemplating starting a House of Hospitality will argue, “You have the paper to help support the work.” Yet experience has shown that the work gets support wherever it is started, and the support continues. Some fear that they will withdraw local support from the New York group and the paper. And yet, in spite of flourishing houses in the big cities of Boston, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Louis, they keep going and so do we.

It is true that it is never easy. God seems to wish us to remain poor and in debt and never knowing where we are going to get the money to pay our grocery bills or provide the next meal. While writing this, we have nothing in the bank and are sending out an appeal for help this month.

But we are convinced that this is how the work should go. We are literally sharing the poverty of those we help. They know we have nothing, so they do not expect much and they even try to help. Some of our best workers have been recruited from the unemployed line. They are not going to a magnificent building to get meager aid. They are not going to contemplate with bitterness the expensive buildings to be kept up, and perhaps paid for on the instalment plan, and compare it with their state. They are not going to conjecture as to the property and holdings of the Church and criticize how their benefactors live while they suffer destitution.

The trouble is, in America, Catholics are all trying to keep up with the other fellow, to show, as Peter Maurin puts it, “I am just as good as you are,” when what they should say is, “I am just as bad as you are.”

There are no hospices because people want to put up buildings which resemble the million-dollar Y.M.C.A.’s. If they can’t do it right, they won’t do it at all. There is the Italian proverb, “The best is the enemy of the good.” Don Bosco had a good companion who did always not want to do things because they could not be done right. But he went right ahead and took care of his boys in one abandoned building after another, being evicted, threatened with an insane asylum and generally looked upon as a fool. Rose Hawthorne who founded the cancer hospital at Hawthorne, New York, started in a small apartment in an east side tenement, not waiting for large funds to help her in the work.

Once the work of starting houses of hospitality is begun, support comes. The Little Flower has shown us her tremendous lesson of “the little way.” We need that lesson especially in America where we want to do things in a big way or not at all.

A small store is sufficient to start the work. One pot of soup or a pot of coffee and some bread is sufficient to make a beginning. You can feed the immediate ones who come and God will send what is needed to continue the work. He has done so over and over again in history. We often think of the widow’s cruse when we contemplate our coffee pots. When the seamen during the 1936-1937 strike asked us where we got the wherewithal to feed the fifteen hundred of them a day who wandered in for three months, we reminded them of the loaves and fishes. And they had faith in our good-will, and in our poverty too, for many of them took up collections on their ships after the strike was over to try to repay us. We have four seamen still with us, two of them joining the movement with their whole hearts and contributing everything they have to it. One came back from a trip and gave us all he had, one-hundred sixty dollars.

What is really necessary, of course, and it is not easy, is that one put everything he has into the work. It is not easy to contemplate, of course, but for those who feel called to do the work, if they honestly give everything they have, God takes care of the work abundantly. We have to remember the case of Ananias who was trying to hold out, even while he wished to enjoy the privileges of belonging to the group.

This sounds extreme, but since Father Paul Hanley Furfey published his book, “Catholic Extremism,” people have not been so afraid of the word or of the idea. Father Furfey has played an important part in clarifying ideas, building up a theory of revolution. Lenin said, “There can be no revolution without a theory of revolution,” and that holds good for the Catholic revolution.

“The little way,” faith in God and the realization that it is He that performs the work, and lastly, not being afraid of dirt and failure, and criticism. These are the things which must be stressed in holding up the technique of works of mercy as a means of regaining the workers to Christ.

We have read so many advertisements about germs and cleanliness and we think so much of modern improvements, plumbing, prophylaxis, sterilization, that we need to read again, thinking in terms of ourselves, what our Lord said to His Apostles: “Not what goeth into a man, but what proceedeth from a man defileth him.”

Please understand that we are not averse to the progress of science. We think of cleanliness with longing and never hope to achieve it. We spend money on food instead of on fresh paint and I defy anyone to make an old tenement clean with plain scrubbing. Antique plumbing, which goes with poverty and tenements, cold water, no baths, worn wood full of splinters that get under the nails, stained and chipped baseboards, tin ceilings, all these things, besides the multitudes that come in and out every day, make for a place that gets pretty dirty. And we get plenty of criticism for it, the justice and injustice of which must be acknowledged. Sometimes it rains or snows and then two thousand feet tracking in the muck from the street makes the place hopeless. But if we waited until we had a clean place before we started to feed and house people, we’d be waiting a long time and many would go hungry.

Peter has always stressed the value of manual labor, and that the worker should be a scholar and the scholar a worker. He also firmly believes that those who are considered leaders must be servants. Christ washed the feet of His disciples.

So in the history of the Catholic Worker, we have all done a good deal of cooking, dishwashing, scrubbing of toilets and halls, cleaning of beds, washing of clothes, and in a few cases even of washing human beings. (Once Peter and I were scrubbing the office over on 15th Street, he starting at the front and I in the back. And Peter, believing as he does in discussion, paused again and again to squat on his haunches while he discoursed, I having to stop in order to hear him. It took us all day! He is a better scrubber than he is a dishwasher. You have to put all your attention on greasy dishes when you heat all the water to wash up after sixty people. Another time I was washing baby clothes for one of the girls in the House of Hospitality and Peter joined in the rinsing of them. Now there are so many of us on Mott Street that there is a distribution of toil, and a worker is liable to take offense if his job is taken away from him even for a day, regarding it as a tacit form of criticism. But on the farm there is always plenty of opportunity for the most menial tasks.)

Also, most important of all, one must not be surprised at criticism. We all find it hard to take, and one good thing about it is that it shows us constantly how much pride and self-love we have. But take it we must, and not allow ourselves to be discouraged by it. It is never going to be easy to take, and it is a lifetime job to still the motions of wrath on hearing it. Criticisms such as these:

What good does it all do anyway? You don’t do anything but feed them. They need to be rehabilitated. You might better take fewer responsibilities and do them well. You have no right to run into debt....

In regard to the debt, all of us at the Catholic Worker consider ourselves responsible for the debts we contract. If our friends did not come to our assistance, if we did not make enough by writing and speaking and by publishing the paper to pay them, and if therefore we were forced to go “out of business” as the saying is, we would all get jobs as dishwashers or house workers if necessary and pay off our debts to the last farthing. And our creditors know this and trust us. At that, we have fewer debts than most papers, considering the coffee line and the number of people we are supporting.

All criticisms are not reasonable. One woman writes in to tell us we must get separate drinking cups for all the men. A man writes to tell us to serve oatmeal and a drink made of roasted grains and no bread. For a thousand people. And the latest criticism is the following, written on a penny postal and not signed. It is the second of its kind during the week.

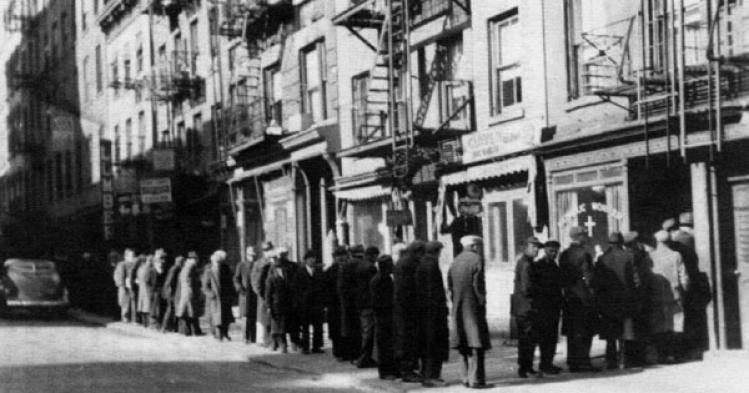

Out of curiosity I stopped at your bread line today. I saw several men making (as they term it) the line two or three times, actually eating the bread in the line. This is the schedule of a number of the men in whom you are interested: 1st trip, South Ferry, breakfast; 2nd trip, morning, 115 Mott Street; 3rd trip, morning, St. Francis, West 31st Street. I heard Jack tell Tom he must go right then to Water Street, be there not later than 11:45 so as to be in time for South Ferry at one o’clock. The writer ventures to say that 95 percent of your men are not worth powder to shoot them.

God help these poor men, traveling from place to place, wandering the streets, in search of food. Bread and coffee here, bread and oatmeal there a sandwich someplace else, and a plate around noon. Never a meal. Many of them lame and unable to travel, and living on a sandwich and a cup of coffee from morning to night.

There is not much time to think of one’s soul when the body cries out for food. “You cannot preach the gospel to men with empty stomachs” Abbe Lugan says.

So we make our plea for houses of hospitality which in the shadow of the church recall men to Christ and to the job of rebuilding the social order. Catholic France had two-thousand leper houses during that time of emergency in the Middle Ages. We are confronted by an emergency today, a need that only Christians can supply. We must bring workers to Christ, as it has been done down through the ages and is being done today in all missionary lands.

I quote the Holy Father [Pius XI] on works of mercy:

The preaching of truth did not make many conquests for Christ. The preaching of truth led Christ to the cross. It is through charity that has gained souls and brought them to follow Him. There is no other way for us to gain them. Look at the missionaries. Through which way do they convert the Pagans? Through the good deeds which they multiply about them. You will convert those who are seduced by communist doctrines in the measure you will show them that the faith in Christ. And the love of Christ is inspired by personal interest and good deeds. You will do it in the measure that you will show them that nowhere else can be found such a source of charity.

[For more of Dorothy Day’s writings from Commonweal, see our full collection.]

[See more from Commonweal’s 1930s archive]