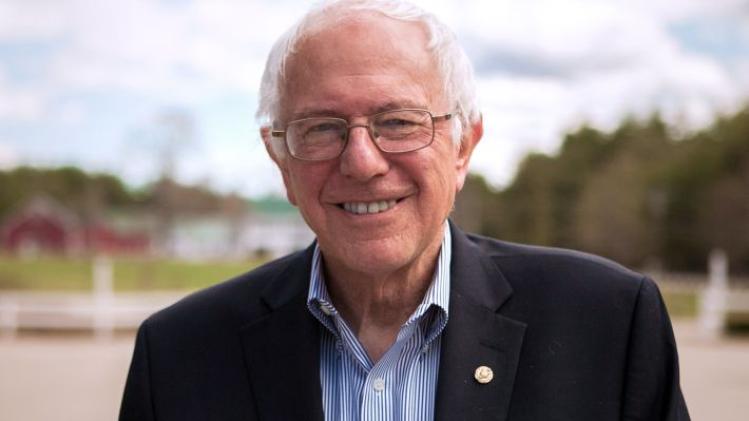

In his much-anticipated speech November 19 at Georgetown University, Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders finally put his ideological cards on the table.

For some, the speech only confirmed suspicions that Sanders is no socialist at all, but really just an old-fashioned liberal. Sanders invoked Franklin Delano Roosevelt's famous 1944 State of the Union address—the speech in which the great architect of the New Deal coalition called for a “second Bill of Rights” that would include rights to employment, education, food, housing, and healthcare.

In Roosevelt's words, the heart of New Deal liberalism was the belief that “true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence.” Last Thursday, Sanders asserted that this basic conviction is the core of his own democratic-socialist vision:

People are not truly free when they are unable to feed their family. People are not truly free when they are unable to retire with dignity. People are not truly free when they are unemployed or underpaid or when they are exhausted by working long hours. People are not truly free when they have no healthcare.

After all the hype, this might disappoint; perhaps “democratic socialism” is little more than a rebranding of the liberalism that dominated American politics in the decades after Roosevelt’s death. As Jedediah Purdy argued in the New Yorker, “Bernie Sanders’s socialism is Eisenhower’s and F.D.R.’s world if Reagan had never happened.” Sanders’s politics, in this account, differs only marginally from Roosevelt's commitment to individual freedom anchored in economic security. And not without some reason. “That was Roosevelt's vision seventy years ago,” announced Sanders. “It is my vision today.”

But on closer inspection it seems that Sanders does not share F.D.R.’s vision entirely. In fact, he usually leaves out a key component of New Deal Liberalism: the part about liberty.

In his Georgetown speech Sanders spoke the language of New Deal liberalism, describing the problems of hunger, retirement, and unemployment as problems of meaningful liberty denied, a kind of unfreedom. But this was out of character for the Vermont senator. Almost without exception, Sanders has described the injustices of our economy not as cases of unfreedom but as cases of unfairness.

Roosevelt's rhetoric consistently described economic injustice in terms of unfreedom. What was most appalling about the unregulated economy was that “life was no longer free; liberty no longer real; men could no longer follow the pursuit of happiness.” When speaking of hunger in America, however, Sanders’s natural tendency is to highlight the grotesque unfairness of a society that lets children go hungry while giving tax breaks to the rich. Roosevelt was more likely to highlight the fact that hunger was a denial of freedom from want, a freedom that was essential if Americans were to pursue happiness and not mere subsistence.

The political theorist Michael Walzer once described liberalism as, in large part, a commitment to the notion of one’s life as a project, as opposed to a notion of a life being determined by one’s inheritance. This is precisely the commitment that Roosevelt sought to defend. He railed against “the new economic royalty” not so much because economic inequality was unfair, but because such inequality had generated an “industrial dictatorship” that controlled the wages, hours, and working conditions of laborers, thereby denying them the latitude to engage in their own self-directed pursuits of happiness.

Just as in 1776, when a previous form of tyranny denied individuals the freedoms of assembly, speech, and worship, these new royalists stifled freedom in the economic realm by manipulating savings and investments, by thwarting the initiative of small businessmen and merchants, and by replacing free enterprise for the many with privileged enterprise for the few. Roosevelt’s liberalism might have been new, but the language of liberty was not.

By contrast, Bernie Sanders speaks less of the denial of freedom and more of political corruption and current assaults on fairness, economic and otherwise. He desperately wants us to recognize that current levels of economic inequality are morally indefensible and that the current amount of money in politics is nothing less than oligarchical. But apart from his recent paean to F.D.R., his message is largely bereft of the words “individual,” “freedom,” and “liberty.”

Perhaps Bernie is a New Dealer without the liberalism. Is this the future of the progressive movement? If so, it is yet to be seen whether a durable American majority can be built without appeals to liberty.