It is a measure of the ruthless efficiency of Nazi genocide that Jews who arrived at the death camp at Sobibor, in occupied Poland, had on average three hours left to live. This stark fact looms over Lawrence Douglas’s narrative of the legal saga of Ivan Demjanjuk, the Ukrainian national and twice-denaturalized American citizen who was convicted in 2011 by a German court of “serving as an accessory to the murder of at least 28,060 Jews” at Sobibor. By the time the court in Munich reached that emphatic decision, there had been more than thirty years of legal proceedings, including trials in three different countries. In a compelling yet intricately argued study, Douglas, a professor of jurisprudence at Amherst College, recounts the courtroom drama of Demjanjuk’s trials while examining the complexities of how legal systems in the United States, Israel, and Germany have handled crimes committed during the Holocaust.

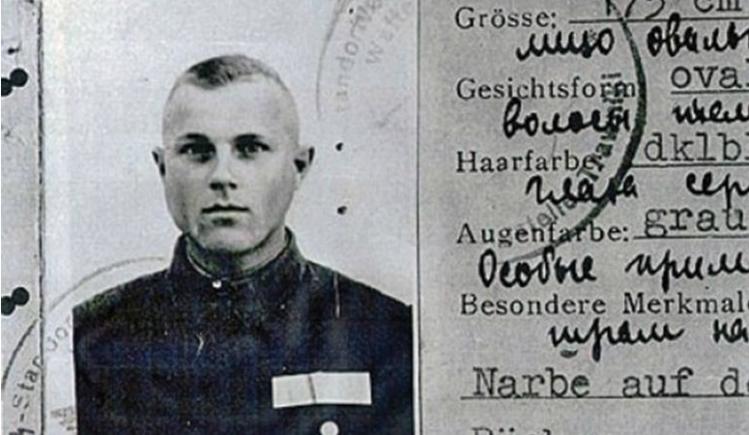

The legal drama rests on a circuitous personal story. Following World War II, Demjanjuk—drafted into the Red Army in 1941 and subsequently captured by the Germans and trained as a camp guard—carved out a new life for himself, first as a refugee in Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Germany and then as a civil employee in the U.S. Army. By 1950, married and with family in tow, he emigrated to the United States, became a unionized auto worker, and changed his name from Ivan to John. It seemed he had escaped his past and created a new life. But eventually that past caught up with him. The postwar period saw intermittent public demands to investigate DP immigrants in the United States in hopes of identifying Nazi collaborators; and the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, which Douglas has written about before and returns to in this book, alerted the world to the existence of Nazi war criminals who had escaped arrest.

Yet the wheels of justice move slowly, and perhaps never more so than in these cases. It was not until 1973, for example, that the United States extradited a naturalized citizen—Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan, a guard in the Majdanek death camp—to face charges for Holocaust-related crimes. That case sparked a push to pursue Nazi collaborators more intensively, and led to the establishment of a Special Litigation Unit (SLU) within the Immigration and Naturalization Service. As Douglas writes, U.S. prosecutors determined that charges could not be filed against Nazi collaborators “because the alleged crimes—committed on foreign soil against non-US citizens—violated no U.S. law at the time.” The United States could only pursue denaturalization and deportation of suspected war criminals, leaving other national courts to file criminal charges.

In 1975, John Demjanjuk’s name surfaced on a list of alleged war criminals. Douglas chronicles step by step how the government built a case charging that Demjanjuk had trained at the SS facility at Trawniki, served as a guard at Sobibor, and ultimately “had run the gas chamber at Treblinka.” Though the latter accusation was never proven, in 1984 a court ruled against Demjanjuk, paving the way for his denaturalization and subsequent deportation to Israel, which had issued a warrant for his arrest.

Unlike the United States, Israel could charge perpetrators with genocide, and Demjanjuk was prosecuted as Ivan “The Terrible” Grozny, a notoriously vicious guard who worked the gas chambers at Treblinka. In 1988, the court found him guilty and sentenced him to death. But Demjanjuk, as the title of this book tells us, was the wrong man, a fact that would soon be revealed by unexpected world events. Before his appeal could even be heard, the Iron Curtain fell, and the archives of the former Soviet Union became available. Those archives disclosed that Demjanjuk was not, in fact, Ivan the Terrible of Treblinka—that Ivan was a different Ukrainian, Ivan Marchenko. In July, 1993, the Israeli Supreme Court overturned Demjanjuk’s conviction.

But his story was far from over. Following the reversal of his conviction, Demjanjuk was returned to the United States, where the government soon began to build a fresh case against him. This time the prosecution drew heavily on the research of professional historians. Those historians’ efforts detailed Demjanjuk’s Trawniki training and guard duties in Majdanek, Flossenbürg, and Sobibor. Their report also revealed the central role Sobibor served in the Nazi apparatus of torture and death—making clear, once and for all, the difference between a concentration camp and a death camp, a distinction that had eluded jurists in several important cases.

In early 2008, the government won its case, and Demjanjuk, by now in his late eighties and ailing, once again was denaturalized and deported—this time to Germany. Behind this request was Thomas Walther, a retired judge serving as an investigator in Germany’s Office for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes. In 1939 Walther’s father had hidden two Jewish families and helped them escape Nazi Germany, and now the son proved to be a tireless tribune in the same cause. Unlike Israeli law, German law had not evolved to include genocide as a prosecutable charge, and those who committed genocide during the Holocaust could only be charged with ordinary murder; for a conviction, moreover, proof of Einzeltäten—specific acts of murder—had to be documented and proven. Additionally, German law defined the status of perpetrator quite narrowly; indeed, Douglas posits that had Eichmann been tried in Germany, he might have only been convicted as an accessory.

Recognizing these obstacles, Walther and his colleague, Kirsten Goetze, adeptly centered their case on Demjanjuk’s time in Sobibor, a death camp that existed solely to exterminate Jews. Here the work of professional historians proved crucial, showing that as a Trawniki stationed in Sobibor, Demjanjuk would have inevitably participated in the killing process, and further that captured Soviet soldiers like Demjanjuk “categorically ceased to be POWs” once they entered service. Nor were they punished for refusing to take part in the murder of Jewish prisoners—another important and damning point established by historian testimony. Though a few of the remaining survivors of Sobibor did testify, Douglas believes that the crucial evidence rested upon the testimony of historians—and when that evidence was weighed by the panel of judges, Demjanjuk was convicted. Before his appeal could be heard, Demjanjuk—the only person in U.S. history to lose his citizenship twice—died in a Bavarian nursing home. To the bitter end he stoutly refused to express remorse.

Though Douglas is troubled by Demjanjuk’s refusal to face his murderous past, he portrays the conviction as a crucial paradigm shift in German law, one that enabled prosecutors to charge collaborators with murder for simply having worked in death camps. The verdict means that the remaining “faceless facilitator[s] of genocide”—at this point, it must be said, a handful of nonagenarians—may have to stand in court to face their complicity in one of history’s worst narratives of horror. In establishing this important fact, Lawrence Douglas’s immensely readable book absorbs the reader in the twists and turns of the Demjanjuk saga, helping us understand both why justice required prosecuting Demjanjuk for his “egregious moral complicity,” and how the job got done.