Upon arriving in Colorado’s Supermax prison in 1999, Timothy McVeigh met Ramzi Yousef. Held in adjacent cells, the men became acquainted in the one hour a day allotted for human contact. McVeigh, who destroyed the Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995 with a truck full of explosives, killing 168 people, apparently spoke with Yousef, architect of the World Trade Center bombing in 1993, through the fence separating each prisoner from his neighbor.

Pankaj Mishra sees the encounter between the two terrorists as the “most illuminating coincidence of our time.” It conveys Mishra’s central theme: that the “unprecedented political, economic, and social disorder that accompanied the rise of the industrial capitalist economy” in the nineteenth century is now “infecting much vaster regions and bigger populations.”

In both eras—the nineteenth century and now—those left behind as new technologies created enormous wealth reacted with fury, forming solidarities of the alienated to combat helplessness and envy. In both eras, too, global connections between peoples accelerated. Our own Age of Anger makes sense only in light of these earlier convulsions and the ability of ordinary Americans, South Africans, and Italians to see how their more affluent compatriots live.

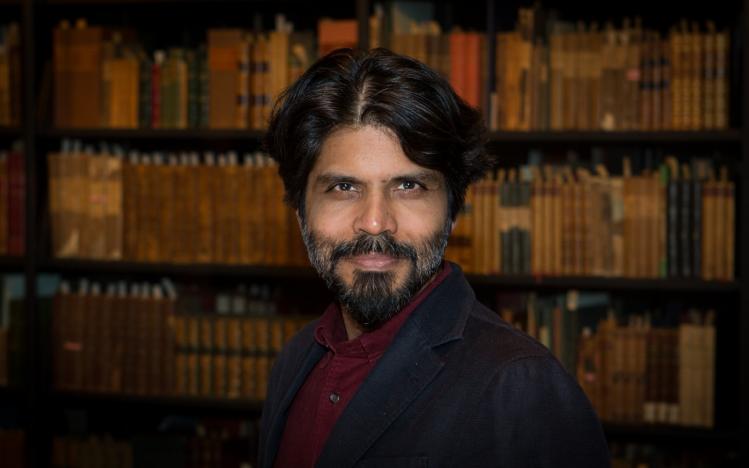

Originally from a small village in India, Mishra is an accomplished essayist and novelist whose recurring theme is the relationship of modern Asia to the West. Among Anglophone academics he is best known for an eviscerating review of Niall Ferguson’s comically triumphant Civilization: The West and the Rest and he is a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books. He began pondering the relationship between nationalism and globalization in response to watching family members and friends express their support for the Hindu Nationalist party. He began writing this book just after Donald Trump declared his candidacy for President. He finished writing the same week that Britain voted to leave the European Union.

Published just as Donald Trump took the oath of office, Age of Anger is well timed to reach an audience craving explanations for this bewildering sequence of events. Mishra’s first historical study, From the Ruins of Empire, published in 2013, traced how intellectuals from India and China absorbed and reformulated Western ideas of modernity. Many of these figures, notably Gandhi, were themselves torn between two worlds, and over time Gandhi shifted from wearing the bespoke suits suitable for a London barrister to a traditional dhoti. But Gandhi was also assassinated in 1948 by a Hindu nationalist convinced that Gandhi’s conciliatory gestures toward Indian Muslims threatened the country’s Hindu identity.

Age of Anger strikes many of the same notes, and includes, for example, an absorbing discussion of how Russian anarchists, emerging from a society only partially modernized, are the predecessors of today’s Islamic militants. Just as anarchists wavered between denouncing the imposition of Western values and recognizing their allure, so too did Mohammed Atta, the leader of the 9/11 attacks, lurch between having drinks with friends at local bars in Hamburg and bemoaning the effects of Western urban planning on Cairo and Aleppo.

Back to McVeigh and Yousef. The two men were born five days apart in 1968 on opposite ends of the globe. The son of divorced Catholic parents living near Buffalo, McVeigh struggled to find a sense of purpose after leaving high school and abandoning college. He had few close friends and a single girlfriend. He joined the army and served during the first Gulf War. His experience of combat was alienating and he later spoke of his regret at killing unarmed Iraqi soldiers. His fascination with guns and festering hostility toward the federal government then propelled him into the shady world of white nationalist militias. He wrote letters to the editor decrying a “democracy” incapable of resolving “America’s frustrations.” Outside Waco, Texas, where FBI agents had launched an assault on the Branch Davidian compound, McVeigh handed out leaflets decrying governmental tyranny not long before he planned the attack in Oklahoma City.

Yousef studied electrical engineering in Wales before moving to Pakistan. He learned to make bombs in a Peshawar training camp organized by a Muslim radical—Osama bin Laden—himself infuriated by the presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia. In a letter sent to the New York Times after the 1993 Trade Center bombing and before his capture, Yousef demanded an end to both American support of Israel and an American military presence in the Middle East. After McVeigh’s execution, Yousef said “I have never (known) anyone in my life who has so similar a personality to my own as his.” McVeigh in one of his last interviews defended Yousef’s actions as understandable in light of U.S. foreign policy.

Both McVeigh and Yousef are extremists, and neither represents either Trump supporters or Pakistani Muslims. But for Mishra a “nativist radical right” and “radical Islamism” have emerged against a common backdrop of economic decline and social fragmentation. Their meeting in Colorado from this vantage point is one revealing episode in a much longer story of globalization and then nationalist reaction, unfolding over a two-hundred-year period that began with the French and industrial revolutions. If the sages of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment conjectured a world of progress and universal reason, contemporaries such as Rousseau and other “latecomers to modernity” stressed the tribal importance of belonging and community. As capitalism in its modern form edged across the world, intellectuals in Cairo and Calcutta, not just New York and London, became local Rousseaus, hoping to gain a better grasp of social relationships in a world defined by increasing trade and rapid communications.

Much of Age of Anger is an explication of this seesaw relationship between systems of democracy and capitalism and the uneven experience of these systems. Mishra jumps from religious nationalisms in the nineteenth century (as in Poland) to the failed secular nationalisms of the postcolonial era (as in Egypt) to the present. After the 1960s, as the economic benefits of capitalism increasingly accrued to a global elite, the reaction against that elite manifested itself not just in the lesser developed world but in Europe and North America.

Mishra is almost incapable of writing a boring sentence, but the haphazard architecture of Age of Anger reflects its speedy composition and gaps in the logic of his argument. He might do more than he does with the fact that alienation does not always equate to economic impoverishment. Yousef, after all, was a trained engineer and abandoned a potentially comfortable life. He also glides over the extraordinary (if admittedly uneven) benefits of capitalist development in the late twentieth century and how these have enhanced human possibility across the globe, not just awakened feelings of envy or frustration. The evidence is most compelling in a once impoverished and now prosperous East Asia, but not only there. Timothy Garton Ash in a recent mordant essay on the fate of Europe after Brexit notes that the only thing worse than the market revolution in Poland after 1989, would have been not having a market revolution. In 1989 Poland’s economy equaled the Ukraine’s. Now it’s three times as large.

Democracy in Poland, as Ash concedes, is also volatile, with a populist (and strongly Catholic) government seemingly bent on weakening an independent judiciary and free press. And democracy in Turkey, Russia, and China is more fragile still, or nonexistent.

Only one public intellectual in the world, Mishra concludes almost off-handedly, now has the capacity to offer a plausible alternative to contemporary forms of global capitalism and a reactionary nationalism. Who is it? The answer may surprise Commonweal readers.

It’s Pope Francis. No one, in Mishra’s view, has more credibility on the related challenges posed by economic inequality and climate change. Laudato si’, in fact, can be understood as an effort to meld environmental and economic thinking into a new vision for human development and care for our “common home.”

The irony is palpable. Many—although not all—Enlightenment thinkers saw the church as the most vehement opponent of a universal human reason, and papal suspicions of democratic politics lasted well into the twentieth century. Now Mishra and the editorial page of the London Guardian identify Pope Francis as the world’s foremost “champion of humanity.” (Meanwhile, some Catholics downplay their own Pope’s teaching on environmental and economic topics.) Full credit to Mishra, then, for his effort to identify and explain present challenges. Or to quote Pope Francis, the task is to improve a world where “some are mired in desperate and degrading poverty, with no way out, while others have not the faintest idea of what to do with their possessions.”

Age of Anger

A History of the Present

Pankaj Mishra

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27, 416 pp.