David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night

The Whitney Museum of American Art, July 13–September 30

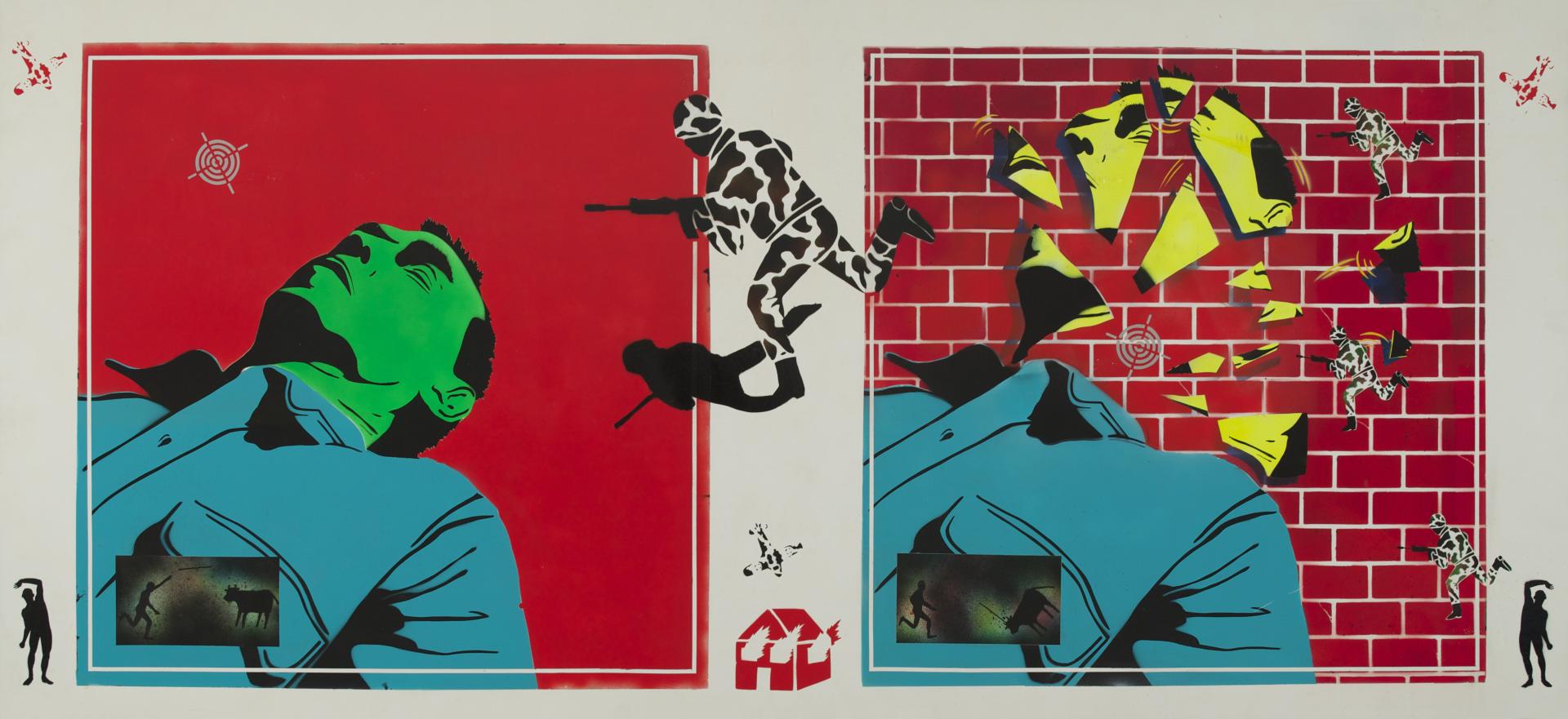

“To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications”: these words introduce History Keeps Me Awake at Night, a survey of David Wojnarowicz’s work recently on exhibit at New York’s Whitney Museum. Now an icon of 1980s and ’90s AIDS activism, Wojnarowicz (pronounced “voy-na-row-vitch”) took precisely that action, creating art that revealed deeply personal outrage in an era when the lives of LGBTQ people were considered expendable. While the AIDS epidemic (and politicians’ willful apathy toward it) was at the front of his mind, Wojnarowicz’s resistance was rooted in wider, more universal concerns—gay rights, but also care for the poor and the victims of global capitalism. His oeuvre reads, in his own words, as “an iconography of crisis and vulnerability,” spurred by a desire to amplify long-suppressed voices. It wasn’t important that you liked his art, he insisted: merely that it did something to you, that it provoked. Twenty-six years after Wojnarowicz’s death from AIDS-related complications, the Whitney’s retrospective finds new relevance, resonating with calls for change in contemporary America—a divided nation, unified in familiar apathy toward those at the margins.

Wojnarowicz worked in a striking variety of media, from gelatin silver prints and paintings to plaster and collage. Yet his art isn’t that cutting-edge; his aesthetic is heavily predicated on art that preceded it. (“History Keeps Me Awake at Night” suggests, after all, engagement with the past.) His work built linearly on the burgeoning “trash aesthetic” of New York’s 1960s avant-garde, a political mode of representation introduced by artists like Claes Oldenburg and Jack Smith.

The show’s early works point to Wojnarowicz’s place in this canon of outcasts. Like other artists from the era, he was influenced by the early modernist poet Arthur Rimbaud, viewing him as something of a kindred spirit—not least because Wojnarowicz was himself also a writer. Rimbaudian formulations like “Je suis un autre,” or “I is an other,” shaped Wojnarowicz’s self-perception as a social outcast, cognizant of but powerless to confront the world’s madness. This is reflected in a series of gelatin silver prints in which Wojnarowicz’s friend, wearing a Rimbaud mask, is posed in various scenes from New York’s underbelly: a displaced flâneur alongside hanging carcasses in the Meatpacking District, or sitting among strangers on a heavily graffitied subway.

Like Rimbaud, Wojnarowicz’s self-perception was one of a social outcast cognizant of (yet powerless to confront) the world’s madness. Part of the beauty of Wojnarowicz’s work is his deep humility: an understanding of his own smallness in the order of things, yet an insistence that his voice is important all the same. The heart of Wojnarowicz’s message is his latent Catholicism, which shapes his conception of the world as marred by institutions of power that fail to understand or stand up for the little guy. Raised Catholic, though scarred by hatred toward the LGBTQ community, Wojnarowicz saw Jesus for the compassionate revolutionary he was, a companion of tax collectors and prostitutes. Take Untitled (Genet After Brassai), a collage that features Jesus in the background, a needle in his arm, and the French novelist Jean Genet in the foreground, a glowing orb behind his head suggesting sainthood. The collage received considerable backlash; the American Family Association (AFA) focused solely on Wojnarowicz’s depiction of Christ in a venomous mailer denouncing his work in general. When Wojnarowicz sued, he was awarded a single dollar in damages.

Wojnarowicz knew that the hatred he received stemmed from fear. In “The Burning House,” an essay on Wojnarowicz’s representations of a society in crisis, Hanya Yanagihara asserts that his work was not just about being gay in homophobic times, but a meditation on a deeper reality haunting the nation: “America has always hated some part of itself.” In footage from a late ‘80s interview, Wojnarowicz claimed that the representation of LGBTQ people “frightens ‘them’ the most.”

In their chronological arrangement, one can sense building urgency in Wojnarowicz’s works; as the artist watched his friends slowly die, his anguish clarified. Throughout a sparse exhibit room, decorated only with placards featuring grammatically incorrect text from a stream-of-consciousness essay, Wojnarowicz’s voice plays: “‘If I had a dollar to spend for healthcare, I’d rather spend it on a baby or an innocent person with some defect or illness not of their own responsibility not some person with AIDS…’ says the texas healthcare official and I can’t even remember what his face looks like, I reached in through the tv screen and ripped his face in half…”

In the face of tragedy, Wojnarowicz was concerned with the restoration of normalcy, equal access to little indulgences that make life worth living. The artist Zoe Leonard once confessed to him that she felt guilty for producing aesthetically beautiful work in such a politically urgent context. But beauty was what they were working toward, Wojnarowicz responded. “Don’t ever give up on beauty.”

At many points, Wojnarowicz’s work is strikingly beautiful. Take Peter Hujar Dreaming/Yukio Mishima: Saint Sebastian, a mesmerizing painting dedicated to Hujar, a celebrated photographer and Wojnarowicz’s confidante, mentor, and best friend. Wojnarowicz used acrylic and spray paint to depict the torso of Saint Sebastian in deep purple, outlined with fuschia, bright yellow arrows protruding from his torso and arms. At his stomach, Hujar’s head dreams in deep forest green, all set against a starry night sky. In a series of four flower paintings, photographs and printed text adorn the peripheries of exotic flora depicted in rich, vibrant tones. The artist’s own Self-Portrait of David Wojnarowicz reads like an icon. Created with photographer Tom Warren, Wojnarowicz stares back at the viewer, arms gently folded, emitting flames of fiery yellow and red from his side. Half of his face is covered by collaged maps; clocks as delicate as jewels run down his right forearm.

In later years, Wojnarowicz was drawn back to the power of language, incorporating text that played off violent, ominous imagery in paintings and shadowy gelatin silver prints. Untitled (Sometimes I Come to Hate People), for instance, depicts outstretched bloody, bandaged hands covered with red text. “Sometimes I come to hate people because they can’t see where I am. I’ve gone empty, completely empty and all they see is the visual form: my arms and legs, my face, my height and posture, the sounds that come from my throat.”

Perhaps this hatred was, to Wojnarowicz, justified: a counterpoint to the political apathy that he believed killed Hujar. He was in the room when Hujar died from AIDS-related complications on Christmas Day, only a few months after his initial diagnosis. Wojnarowicz asked everyone to leave so he could be alone with Hujar, and, in these final moments, took a series of twenty-three photographs of his friend’s head, hands, and feet. The haunting images capture the essence of where Wojnarowicz was trying to work, at the confluence of beauty and tragedy. “I kept trying to get the light I saw in that eye,” he later wrote in his memoir, “Close to the Knives”

I mean just the essence of death...it contains this body of my friend on the bed this body of my brother my father my emotional link to the world this body I don’t know this pure and cutting air just all the thoughts and sensations this death this event produces in bystanders contains more spirituality than any words we can manufacture.

Aware of his own limited time, Wojnarowicz began producing some of his most unnerving work, including What Is This Little Guy’s Job In the World in 1990. It’s a gelatin silver print depicting a cupped hand holding a tiny frog, no bigger than an inch, peering over the thumb’s edge, with text in the upper right-hand corner.

What is this little guy’s job in the world. If this little guy dies does the world know? Does the world feel this? Does something get displaced?...What shifts if this little guy dies? Do people speak language a little bit differently? If this little guy dies does some little kid somewhere wake up with a bad dream? Does an almost imperceptible link in the chain snap? Will civilization stumble?

David Wojnarowicz died on July 22, 1992, two months short of his 38th birthday. That his name isn’t a household one, or readily included in today’s mainstream canon, likely wouldn’t have troubled the artist. When his biographer, Cynthia Carr, congratulated him for his inclusion in the 1985 “East Village graffiti” Whitney Biennial, he scowled and affirmed his hatred of the art world. In the exhibition’s catalogue, Carr quotes him as saying, “If I were straight, I’d move to a small town right now and get a job in a gas station.”

Twenty-six years later, 1.1 million Americans continue to live with HIV. Crises new and old—the opioid epidemic, detention of migrant children, structural racism, poverty—still inflict their pain on far too many Americans. But in the face of these injustices, and countless more that go unnoticed, Wojnarowicz’s creations remind us not to go down without a fight, to use all necessary means to make our voices heard. In the artist’s own words: “With enough gestures we can deafen the satellites and lift the curtains surrounding the control room.”