Over a long career, Justo L. González has written prolifically and responsibly in the field of historical theology, and in his eighty-fourth year offers a brief but deeply informed introduction to the formation and interpretation of Scripture as the Church’s book. His target readership is the mythical educated layperson rather than fellow professionals. His prose is correspondingly free from scholarly affectation, his tone that of the patient expositor. He grinds no axes and airs no grievances. And while he does not touch on everything an interested neophyte might want to learn, he manages to convey a considerable amount of information in less than two hundred pages.

The book has three parts that treat, respectively, the shape of the Bible, the use of the Bible, and interpretation of the Bible. González focuses mainly on antiquity but some of his discussions move into medieval and even modern times. An extensive “cast of characters” at the back of the book provides thumbnail sketches of the authors González discusses in his text.

In his discussion of the Bible’s “shape,” González deals primarily with the material dimensions of Scripture, beginning with its contents. What were the cultural contexts and languages employed in the writing of the Old Testament, and how did Hellenistic Judaism’s Greek translation (the Septuagint), which was adopted by the first Christians, lead to two distinct canons that even today distinguish Catholic and Protestant versions of the Old Testament? What were the factors at work in the formation of the New Testament canon? While the points he makes are historically responsible, and are certainly helpful to readers totally ignorant of such matters, I found it puzzling that González gives no attention to the kind of prior questions that most demand consideration: What sort of experiences among the tiny and insignificant people of ancient Israel led to the production of such breathtakingly original and compelling writings in the first place? And what sort of experiences impelled the followers of a failed messiah to compose the writings that make up the New Testament, the most tension-filled religious literature ever written?

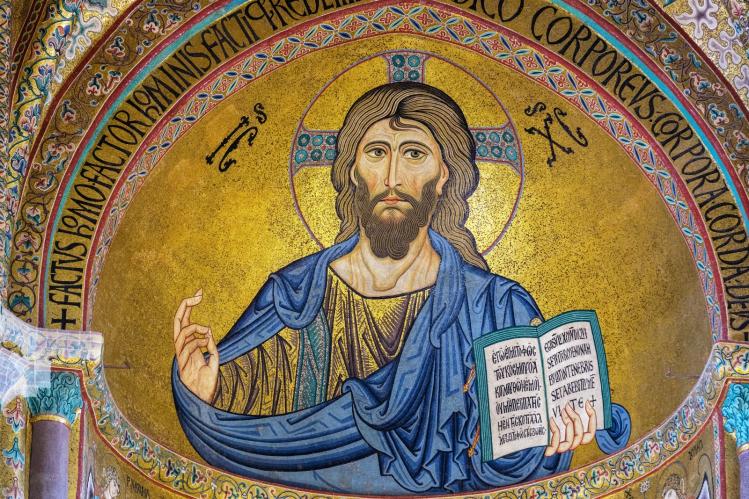

Concentration on the material aspects of the Church’s book continues through the remainder of Part One, as González treats in turn “the physical appearance of early Christian Bibles,” “chapters and verses,” “the transmission of the text,” and “from manuscripts to printed Bibles.” In these discussions, each of them well informed and instructive, González considers mainly the physical evolution of the New Testament through the centuries, making the simple but important point that the printed and translated Bible that is held and read by present-day Christians did not fall from heaven but is, down to its very punctuation, a “work of human hands.”

In Part Two, González takes up some of the ways in which the Bible was used in the ancient Church, beginning quite properly with its use in worship. Here, the time he spent on the material aspects of the Bible shows its pertinence: before the invention of printing, the experience of Scripture was necessarily liturgical. For most believers, Scripture was not read but heard, and such an oral/aural engagement continued for some fifteen hundred years. González notes the importance of the reader as an ordained position in a largely illiterate population, and the significance of preaching as the primary site of patristic theology. He shows how the shape of the Christian liturgy built on the practice of the synagogue, but he could also perhaps have devoted some attention to the way in which the classic forms of the Eucharist also drew their very language from the Old and New Testaments, so that Scripture was embodied and enacted in the practice of prayer.

As González goes on to show, the liturgical enactment of the Bible is found especially in the communal singing of the psalms, a practice that goes back to the very beginning of the Christian movement. The practice was then extended from common worship to the monastic practice of chanting the psalms, and also to private reading among those with access to texts (or who memorized the psalms through constant repetition). Every observation González makes on this topic is pertinent, and it is legitimate to draw the conclusion that abandoning the practice of such communal singing of the psalms has led to the loss of what can be called a “scriptural imagination”—that is, the capacity to imagine the world as the psalter imagines it, a world porous to the presence and power of God.

From this liturgical starting point, González shows how, despite the paucity of manuscripts and the scarcity of literacy, the private, devotional reading of Scripture was by no means unattested among believers in the patristic and medieval periods. Such personal reading was not the invention of Protestantism and the printing press, although those ideological and technological revolutions can serve to obscure their more modest precedents. Similarly, the Bible was the essential tool for efforts to shape a distinctively Christian education, one that drew from the riches of Hellenistic culture while simultaneously subverting and transforming that culture. An essential element in this education was a vision of a righteous social order drawn from the Old Testament and New Testament alike. As a young sect, Christianity appealed to Scripture as it stood against the idolatrous claims of empire; as the authorized religion of the empire, it made Scripture the basis for social teachings and practices that ameliorated the complexities and corruptions of the establishment.

Part Three deals with interpretation of the Bible. González first shows how the New Testament continued the Old Testament’s practice of rereading earlier texts and events, in three modes: the prophetic (statements made long ago find their “fulfillment” in the present), the typological (events of the past anticipate and find expression in present events), and allegorical (texts bear not a single meaning but several levels of meaning). By showing how these modes are found in the New Testament itself, González makes the subsequent use of these modes by Christian interpreters appear less innovative or even alien.

The payoff of all this patient exposition is found in substantive chapters devoted to the patristic interpretations of three “crucial texts”—those concerning creation, the exodus, and the Word. In these discussions, González displays his impressive command of early Christian literature as he elucidates the issues in the texts with which the ancients struggled, notes the variety of opinions found among diverse authorities, and identifies the points of agreement among them. These discussions serve to show less-knowledgeable contemporary readers that intellectual struggles with Scripture are not new, that the Church’s tradition has included a diversity of opinion even on “crucial texts,” and that Christians today have much to learn from such ancient conversations.

In a succinct final chapter, González draws three lessons: first, we would not have the Bible at all without the countless believers who not only preserved Scripture but shared it; second, as we observe the errors that entered into the process of transmission, we need to learn humility in our own handling of Scripture; and third, we ought not to be fearful of further transformations in the appearance of the Bible. The Word of God can speak as well in a laptop as from a manuscript: “The Bible is the Word of God not because of its format or appearance but because God speaks to us in it.”

This small book is a gift from a seasoned scholar that combines great learning, clear prose, and rare wisdom.

The Bible in the Early Church

Justo L. González

Eerdmans

$19.99 | 204 pp.