There’s an old debate among Christian theologians about the life of the world to come. Is it a life in which there’s no more to be had, no more to want, no progress to be made, nothing new to come? In which you’ve finally and fully become, without possibility of further growth, what you always already were? Or is it a life in which there’s always more—more understanding, more delight, more intensity, more intimacy with God?

There are eminent voices on both sides of the question, and no magisterial teaching that gets close to resolving it. Augustine is an advocate of the first; he’s a poet of quietus, persuaded to that position, I think, by the depth of his understanding of the disquiet that mars all our lives here below, and by his sense that this disquiet is the thing about us that most needs to be remedied. Gregory of Nyssa is perhaps an advocate of the second, persuaded that the inexhaustibility of God’s goodness requires that our capacity to see and to relate to that goodness should also be inexhaustible, and that we will, therefore, always progress in understanding and love, even in the world to come.

Since I first came to think about this issue about thirty years ago, it’s always seemed to me that of course Augustine is right: when we say of the dead “requiescat in pace,” we’re expressing the hope that they’ll find their rest in peace, as well as our intuition that their peace is only to be had in rest. The other view seems confused about the difference between the order of being, in which God’s goodness is inexhaustible, and the order of knowing, in which we, being finite, are neither capable of endless growth in apprehension of that goodness nor in need of such growth.

The endless-progress view also seems tiring, at least to me. I think I know what disquiet is from having been a human creature in a fallen world for almost seven decades. I don’t need more of it, and to think of the life of the world to come as one new vista after another feels like an exhausting extension of the life I already know. I’d like to be a clear glass filled with God’s light. To be told that, no, I’ll never be filled (or fulfilled) engenders in me a heavy weight of gloom. It would be purgatory without end.

The life of the world to come, I’d prefer to think, is not the provision of ever more goods. Rather, it’s the definitive removal of lacks. Death is a lack that the life of the world to come removes and replaces, finally and fully, with life. So ignorance, another lack, will be replaced by knowledge; desire by fulfillment; pain by delight; and so on. All these absences will be replaced by a presence. We will then be able to live quietly and fully, with nothing more to want. That is, so far as I can see, the content of the Christian hope.

Some, perhaps most, Christians will disagree with me. Some will think that there’s never an end to increase, and that there shouldn’t be. This disagreement persists because Scripture and tradition contain threads that support both views, but also because there are very different understandings of what’s wrong with us. My own sense is that the most fundamental evidence of our condition as fallen is unrest. What we fell from when we fell was precisely the ability to rest in peace. Simone Weil writes somewhere that we have a regrettable tendency to try to eat what we should instead look at—that is an elegant and suggestive summary of the nature of our disquieting desires, and of the way they can never be satisfied. Consuming beauty won’t work, and also won’t end: there’s always more of it to put in your mouth. Repose, by contrast, permits contemplation of what’s there to be seen and calms the desire to consume it.

There are those who think that our problem is not the disquiet of desire but rather being disquieted by the wrong things, and that when we turn our eyes and minds to God we’ll find that we do want—and can have—ever more of the one we love. It’s tempting to depict this view as a half-Christianized version of the American dream, according to which it’s never possible to have enough of a good thing: more is always better. But that analogy isn’t quite fair. Better simply to say that this disagreement about the world to come is one of some moment for Christians, and that we’ve not yet learned how to resolve it.

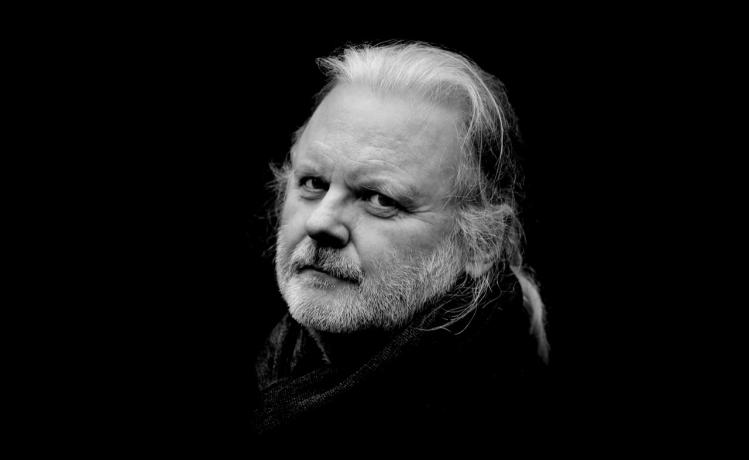

Instead of such a resolution, I present that rarest of literary rarities: a book that attempts to show what it’s like to come to rest by receiving the gift of Jesus, and offers readers a hint of that rest in the form of its prose. I am referring to Jon Fosse’s Septology.

This is a prose poem in three volumes and seven parts, published in Norwegian between 2019 and 2021. In 2022, Transit Books published an English translation by Damion Searls as a handsome single-volume hardcover. Septology is almost seven hundred pages long, amounting to perhaps a quarter of a million words, and it’s written in rhythmic, systolic-diastolic prose, a repeated inhale and exhale. The entire work is devoid of periods, those signs of a stop, and so the only occasions for a long pause are at the end of each of the seven parts—and even here, the sentences don’t end; they simply break off, as though someone had stopped speaking the words of the rosary in mid-phrase. The example is apt: of Septology’s seven parts, two—the first and last—end with the Ave Maria in Latin, once complete and once, at the very end, broken before the final phrase, “mortis nostrae.” The prayer is broken there because the protagonist has died. Each of the book’s other five parts ends with a slightly different depiction of prayer. For example:

I hold the brown wooden cross between my thumb and my finger and then I say, again and again, inside myself, as I breathe in deeply Lord and as I breathe out slowly Jesus and as I breathe in deeply Christ and as I breathe out slowly Have mercy and as I breathe in deeply On me

The paucity of punctuation here slows the reader and begins to assimilate the act of reading to what Fosse is depicting, a prayer. Here Fosse’s prose approaches the condition of a verbal icon. You might be reading Donne’s Holy Sonnets, without the pyrotechnics. You don’t read it; it reads you, if you let it. Of course, if you’re distracted or disquieted, you might not let it. I found it impossible to give the book more than an hour or so at a time: by the end of an hour I was partly dissolved, partly praying, and partly absent.

Septology is not a treatise on prayer, however. Nor is it just a representation of it. It’s also a story, told aslant, of the life of a Norwegian man named Asle, a painter at the edge of old age as the book opens. Asle has been married, but his wife is dead. He learned to paint almost accidentally as a young man and has found painting essential for most of his life, but is now, perhaps, about to give it up. He has a friend (it seems only one), with whom he spends occasional holidays and whose visits he resents as often as welcomes. He has an art dealer, who is almost but not quite a friend. And he has an alter ego of the same name who is, perhaps, himself as he might have been, an aspect of himself. This other Asle is also a painter, though unsuccessful, and in the last, fatal stages of alcoholism. The presentation of the two Asles by Fosse rapidly turns what at first seems an exercise in Kafkaesque parabolic surrealism into bog-standard realism: Of course there’s more than one Asle; how many of you are there, and don’t you meet the others all the time? There’s high literary art in making that seem clearly so. By the end of Septology, prayer allows the protagonist-Asle to stop painting and die.

So Septology has a story, of a sort. But at its heart is the quietus, and Fosse shows this not only by showing readers Asle’s prayer—and making them pray with him—but also by softening the barriers of time. Asle sees, from the perspective of a man with most of his life behind him, events and people from his past. He stops his car, for example, by the side of the road from time to time and watches a young man and a young woman converse and play and argue and love—the kinds of things lovers and spouses do. Is he imagining these scenes, rerunning his past for delight or pain? Fosse shows Asle considering and dismissing this thought. The effect, as with the depiction of the alter ego, is at first surprising, and then not. The boundaries between past and present are soft for Asle. The degree of his identification with a past-him pushing the girl on a swing becomes, as Septology progresses, both as loose and as tight as his identification with the present-him doing the watching. And if a principal source of disquiet is hard identitarianism with respect to oneself—here’s me, there’s all the rest of you—then the softening of the boundary between past-self and present-self is central to the arrival of quietus. The hard-bounded, lovingly polished, carefully protected present selves we’ve enshrined begin to melt, first into their own pasts and futures, and then into those of others.

Then there is painting. Asle is a painter whose discovery of what it is to paint, and whose increase of skill in doing it, is shown sidelong in the book to great effect. He paints not as a means of representing the world (though his paintings are, mostly, of scenes in the world) and not as a means of making a living (though he sells his paintings easily and lives on the income from them), but rather “in a way that dissolves the picture lodged inside me and makes it go away, so that it becomes an invisible forgotten part of myself, of my own innermost picture, the picture I am and have.” Painting, for Asle, is a kind of exorcism by way of transfigurative removal, and what it removes are the shadows of an inner life. In this, it is like prayer. Painting brings peace by removing the disquiet of memories that identify Asle as such-and-so, as having done this or that. Putting those pictures on canvas takes them out of his inner theater, where they have a little life of their own, the kind of life that produces disquiet. Painting thereby permits the true picture to begin to show itself. As a depiction of what it is to make art, this is as far as can be from the clichés dominant in today’s identitarian America, which all suggest that the art we make shows the world who we really are. Fosse’s depiction of Asle’s art suggests that art may instead be a means of jettisoning who we really aren’t—and in that way making us ready to receive Jesus. Once Asle’s paintings have been painted, they no longer matter. Their purpose is exhausted in the painting of them.

Among Asle’s last paintings is a diagonal cross, one arm in purple and the other in green. Asle isn’t sure whether it’s finished. For him, it’s connected with a changed attitude toward painting:

I realize that I don’t have any desire to paint, and it’s been a long time since I haven’t wanted to paint, and then there’s the picture with those two lines that cross, I don’t want to see that picture again, I have to get rid of it, I have to paint over it, because it’s a destructive picture, or maybe it’s a good picture?

But he does finish it—or at least recognizes that it’s finished. He gives it a title (St. Andrew’s Cross), which is, for him, the ordinary mark of a painting’s completion. Should he keep it? Give it to his dealer? Paint it over? The picture appears a dozen times in Septology, and eventually Asle sees not only that it’s finished but that it isn’t like his other pictures. It’s the closest thing to a picture of God, “the picture that’s kind of innermost inside me...God’s shining darkness inside me.” The seeming incompleteness of the picture is its completion, and it’s a cross that completes him. Once Asle comes to see this, he has little left to do but die.

Fosse writes as an evangelist, not by demanding conversion or advocating baptism, but by showing in prose the face of Jesus as the one who brings repose—the one who is repose. To read Septology attentively is to be stilled, to be shown, as Fosse writes, “that I, what’s I in me, can never die because it was never born—nach der Weise meiner Ungeborenheit kann ich niemals sterben.” Fosse here quotes Eckhart, and the whole of this long and beautiful prose poem shows us what it’s like to be an I brought to rest, thus moving us toward the same condition.

Septology

Jon Fosse

Trans. by Damion Searls

Transit Books

$40 | 672 pp.