In a recent, highly public dustup, Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois, raised the question of heresy because of his disgust with calls for greater Eucharistic inclusivity for people who are gay, lesbian, and transgender, or divorced and remarried. His unnamed target was Cardinal Robert McElroy, bishop of San Diego, whose article in America Bishop Paprocki cited. Cardinal McElroy responded by repeating his objection to the traditional moral teaching that all sexual sin is objectively mortal sin. That was the trigger for the heresy charge.

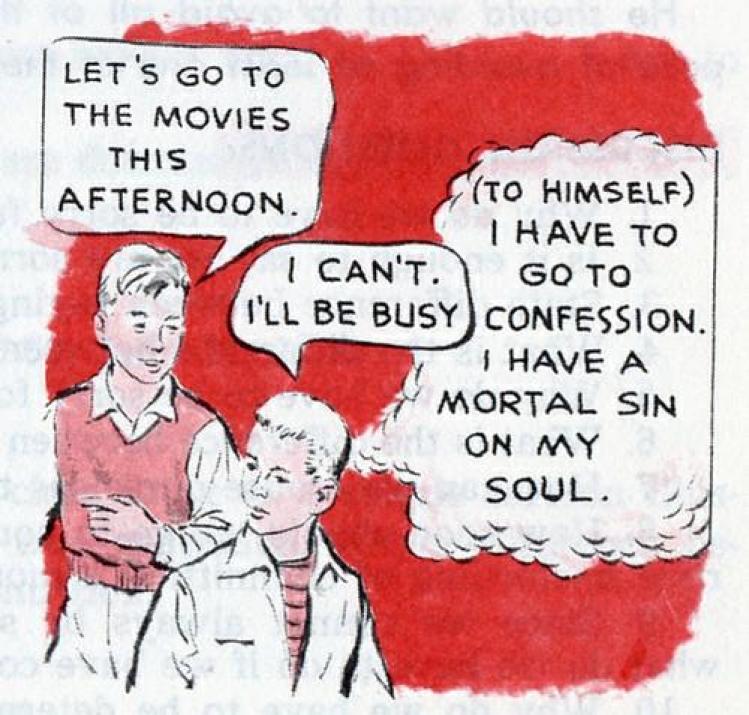

The principle itself—that all sexual sin is mortal sin—would not seem shocking to American Catholics who attended parochial schools in the 1950s. “Mortal” signified the rupture of the soul’s relationship to God, and its eternal damnation if its sins were left unrepented before death. As it happens, not a month after encountering this exchange, I discovered the same declaration on page 260 of the book under review, James Keenan’s A History of Catholic Theological Ethics: “All sins of impurity of whatever kind or species are of themselves mortal.” The source for this (endnote 98, p. 384) was unclear, so I looked it up where someone of my generation would have encountered it: in the Baltimore Catechism. And here it is, from Baltimore Catechism #3: Fr. Connell’s Confraternity Edition, intended for those who had been confirmed or were in high school, authorized in 1949 by the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine. This edition was a revision of the original Baltimore Catechism made by Professor Francis Connell of the Catholic University of America, copyrighted and published by Benzinger Bros. in 1949 and 1952. (Baltimore Catechism #3 was one of four age-appropriate levels in the revision, according to the Wikipedia article on the catechism.) I cite from the free site archive.org:

Question 256. What does the sixth commandment forbid?

The sixth commandment forbids all impurity and immodesty in words, looks, and actions, whether alone or with others.

(c) Immodesty is any deliberate thought, word, or action that tends toward impurity.

(d) When there is full deliberation in any sin of impurity it is a mortal sin. Immodesty may be either a mortal or venial sin depending on the greater or less danger of impurity to which it tends, the degree of scandal, and the intention of the sinner.

Fr. Connell’s parsing of the gravity of sins against the sixth commandment relaxes the absolutism of the original quotation. But the principle itself is reaffirmed: any fully deliberate sin of impurity is mortal.

I begin this way not in order to skewer, once again, the pedagogical shortcomings of preconciliar catechesis. The Baltimore Catechism is an easy target that did its share of harm, though this reviewer thinks it had its redeeming side as well. I begin with it because it offers a direct way into A History of Catholic Theological Ethics. James F. Keenan, SJ, is Canisius Professor of Theology, director of the Jesuit Institute, and vice provost of global engagement at Boston College. He is the prolific author and editor of more than two dozen books, dozens of essays and chapters in books, editor of two academic series, and the founder of Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church. That last distinction has been the focus of his energies in recent years, and the place where this sprawling survey reaches its conclusion. The book is a recapitulation of his three and a half decades of remarkably productive and creative service to the Church and to the theological academy. It reveals his commitment to historical consciousness, to interdisciplinarity, to pastoral practice, to bioethics and issues related to sexuality and gender, and to a global inclusivity.

Despite its ambitious scale, the book sits rather easily with the reader for at least three reasons. First is its relaxed and discursive style. We hear the voice of a writer who is patently a teacher, supportive and encouraging rather than domineering and overweening. He explains at the outset how the book grew out of thirty-three years of teaching: “I am welcoming you into my classroom.” He is a charitable analyst, even of texts whose obsessions with spiritual control and intimidation may irritate many readers. The eighty pages of endnotes tell you how much reading and study went into the assurance of that voice. Fully one third of those endnote pages are from the eighth and last chapter of the book, on “Moral Agency for a Global Theological Ethics”—an indication of the author’s energy and attention for the past dozen years and more.

Second, Keenan has a strong narrative line and an argument that he presses from the beginning to the end. The story he tells is how sin-consciousness gradually captured the Catholic conscience and took hostage the primal message of the Gospel, which is not the conviction of sin but the call to discipleship: “[T]his early classification of such major sins became, I think, the beginning of a terrible mistake, for along the way we lost a sense of the gospel meaning of sin as the failure to bother to love.” Keenan examines in great detail the manuals of moral theology that shaped Catholic life and conscience-formation for the entire period between Trent and Vatican II. But more important than these—or the penitentials of Irish monasticism or the disciplinary regimen of the early Church or the confessional practices of the Middle Ages—are what Keenan calls “pathways to holiness,” the positive call to goodness and to discipleship that is the real message of Jesus:

[I]n lieu of the patristic period as foundational for a sin-oriented ethics that became manifested in the penitentials and the practice of auricular confession, I propose that from the beginning of the church, members sought pathways toward the holy, and the confessing of sin and concern about this matter was only a part of the pathway to holiness and not the overall focus of either the patristic or the medieval period.

That is a large claim and Keenan hangs a lot on it. Chapter Three—at fifty-five pages the second longest in the book—runs us though twelve centuries of history to make the case that the forgiveness of sins was only one stage of the Christian’s growth in the moral life, understood as the cultivation of the virtues and the avoidance of vices by following exemplars of the moral life. There was, he says, a certain dynamism that always pushed the Christian further and further.

From the very beginning, Christianity had the instinct, as in the death of the deacon Stephen, to live beyond expectations, to go further into the land of holiness as Anthony did when, at the age of nineteen, he entered the desert in the third century…the line between the moral life and the life of holiness is not simply found or drawn.

It seems, though Keenan does not say so explicitly, that he chose this language of “pathways to holiness” in order to undo the deeply embedded idea that there is one privileged pathway that sanctions those who take it to be arbiters of the rest who do not—whereas in reality all are on a journey to the same goal, though not by the same routes or at the same pace. I take this to be his way of incorporating the “universal call to holiness” advocated by the Second Vatican Council in order to deepen the dignity of the laity and bridge the lay-clerical divide, grounded as it often has been in the claim to bind or to absolve.

Third, Keenan enlivens his narrative with a gallery of sharply defined portraits of his favorite heroes from the theological tradition. In his Preface, he notes a preference for “innovators” rather than for the “grand achievers” who built on the first steps taken by the innovators. There is Peter Abelard, for Keenan a hero of conscience: “There is no sin, except against conscience,” from Abelard’s unfinished book Scito te ipsum (Know Thyself). Heloise too is featured, for her thought on intentionality. Thomas Aquinas gets fourteen generous pages with special attention to how he shaped the tradition he inherited from Augustine (who is not among Keenan’s heroes) by incorporating Aristotle’s teleology of human nature and thereby opening up the possibility of the virtuous pagan. (In 1992, Keenan published a book titled Goodness and Rightness in Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae, which was based on a course he taught.) There is Erasmus, celebrated for his “distinctively lay, nonmonastic spirituality that could encompass all Christians.” There is Scottish philosopher John Mair, or Major (1467–1550), author of “the earliest full successful work of casuistry in Europe,” which is also the fruit of “a very late form of scholasticism.”

The pages on Erasmus are some of the freshest and most cheering in the book: “The moral life was no longer understood by the devout Christian as the simple avoidance of sin.” Keenan pairs Ignatius Loyola with Erasmus: both had a christocentric focus, believed in the primacy of the individual’s conscience, and privileged the spiritual over the moral.

Keenan also includes the Spanish Dominican Francisco de Vitoria for his adaptation of natural law to recognize what is now called international law, which asserts the rights of all people, by virtue of being human, to their own legitimate dominion—in this case, against Spanish aggrandizement. Keenan pairs de Vitoria with Bartolomé de las Casas, the repentant priest-colonialist who became the great advocate of the Indians, critic of mass and coerced evangelization, and chronicler of Spanish atrocities. Then there is Alphonso Liguori, founder of the Redemptorists, humane confessor, and reformer of moral theology. (Keenan didn’t quite convince me on that one, but where mission preaching is concerned, perhaps grading on a curve is the best one can expect.) By the time Keenan gets to his last chapter on global theological ethics, the parade of names from across the world becomes a little dizzying and an impressive testament to the contemporary catholicity—to invoke a very ancient word—of theological ethics, across every boundary of nation, language, and gender.

Who is this book for, and what will they get out of it? I have already complimented the book’s readability. I would call it a high-level textbook, though a certain level of theological education is presumed. Keenan helps the reader by staying in touch with primary sources and singling out specific works for extended quotation and discussion. And he is forthright and complimentary about secondary literature he relies on and recommends.

He seems most sure-footed in the long section on the manualist tradition after the Council of Trent (Chapter Five) and the extension of that discussion in Chapter Seven, with manualism’s death in the furor stirred up by Humanae vitae—and its resuscitation in new dress in the long reaction to Vatican II that has now come up against the pontificate of Francis. Keenan’s discussions of the origin, development, and decline of casuistry in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are fascinating. So is his coverage of moral-juridical trends like the “probabilism” advocated especially by the Jesuits, and the rigorist and mainly Dominican “probabiliorism” that it provoked in reaction, which in turn inspired the “equiprobabilism” of Liguori and the Redemptorists. The defense of probabilism found on page 198, and attributed to the early twentieth-

century Jesuit Thomas Slater, gives fresh meaning to “jesuitical.” Keenan gives his dry verdict on manualism as the conclusion of Chapter Five: “It is no wonder that for almost four centuries Catholics were fascinated by the principle of double effect. They had nothing else with which to work.”

Keenan’s readers will enjoy the tour in Chapter Eight of contemporary theological ethics around the globe. I found it chastening how few names outside of North and South America I even recognized. Keenan finds two unifying features in all of this diversity: the way attention is now paid to the local and particular rather than to the universal (as it was traditionally conceived); and the focus on suffering—no longer seen as a problem of theodicy (why does a good and omnipotent God allow suffering?) but of human accountability: Why do we tolerate or contribute to conditions and structures that are contingent causes of immense suffering around the world? The registers of suffering run from environmental degradation and climate change to war to gender discrimination, racism, and poverty.

The exhaustion one feels after reading this chapter may tempt one to crisis fatigue and resignation—and perhaps to wonder whether so much talk about others’ suffering can become a cover story of its own: travel, conferences, publications, lectures, as an ersatz reality. But then one remembers the witness of those who died acting on behalf of others’ suffering—and Pope Francis’s indignation against “the sin of indifference,” uttered after the drowning of African refugees in the Mediterranean.

From this book readers will not get substantive discussion of specific issues, though some are favored for illustrative purposes—e.g. usury and contraception. Keenan largely leaves to masters like the late Judge John T. Noonan Jr. the enormously important area of the institutional intersection of law, morality, and religion. I don’t think education and schools are even mentioned. Considering how central, even obsessive, they have been in modern Catholic teaching, that is a revealing lacuna. Just consider how much they occupied the published work of someone like John Courtney Murray—or the Jesuits in their entire history. War and even nuclear war don’t get significant attention. Colonialism and empire, on the other hand, are well covered.

Nor is this a work of history in the normal sense. The treatment of early Christianity seemed kind of disembodied, despite Keenan’s attention to “the body.” It was necessarily topical and tailored to suit the author’s commitment to the importance of mercy over sin as governing motifs. But it wasn’t the primitive Christianity of the first two hundred years or the developed institution of the next four hundred years that I am familiar with. I would have liked to hear more, too, about the changing social and cultural conditions in which the casuists and manualists taught—the early modern preoccupation with certitude and credibility, as revealed in the work of historian Stefania Tutino or Jesuit scholar Michel de Certeau, or the growing power of “confessionalization” in the partitioning of Western Christendom. How much did the unwinding of Christendom in the modern period shape how and what moralists taught? Leslie Woodcock Tentler’s Contraception: An American History (2005) shows brilliantly how increased education (especially of women) at first heightened American Catholic reception of Church teaching on contraception (in the modified form permitted by Pius XII after 1951) and then led to the rejection of the Church’s teaching after the promulgation of Humanae vitae.

On the other hand, Keenan is quite frank that he has not written a work of history as such, nor does he intend to be comprehensive. He has, however, tried to think historically. And he is acutely aware (with full knowledge of the work of people like Noonan) of how teaching has had to change to accommodate new conditions, while avoiding the banal relativism of the “situation ethics” that some propagated two generations ago. In a few well-conceived pages, he makes the case for the historical consciousness famously formulated by Bernard Lonergan, which incorporates experience as a crucial personal appropriation of an objective moral horizon as it emerges with time. His three examples of the Jesuit adoption of probabilism, the Jesuit defense of the Chinese rites as civil and not religious, and the defense of the independent rights of the Guaraní in the Paraguayan reductions are well chosen—if forgivably Jesuit in their focus.

Keenan is also acutely aware of, and stunningly well informed about, how the social, geographical, ethnic, and gender status of those who are doing theological ethics today quite naturally affects the work they do. The practitioners of theological ethics are no longer chiefly clergy taught to treat the confessional as “a tribunal” and the priest as a judge, as they were from the time of the Council of Trent. They no longer—as early and mid-twentieth-century moral theologians were increasingly made to do—write with the Roman magisterium as their primary intended audience.

I am guessing that many readers of this book have probably abandoned the weekly confessional practice of their parents and grandparents. My own parish church has eight or ten massive marble confessionals whose utility is not what it once was, much though many American bishops might wish it were otherwise. People simply stopped going, as one of the priests with whom Tentler speaks in her book says in wonderment. Readers of A History of Catholic Theological Ethics will come away with a powerful explanation of why that happened and what serious attempts are now underway to give conscience and discipleship their due.

A History of Catholic Theological Ethics

James F. Keenan, SJ

Paulist Press

$49.95 | 456 pp.