Pilgrims arrive at the Villa Guadalupe in Mexico City between December 9 and December 12, the Día de la Virgen de Guadalupe. They walk, bike, drive (or are driven) from all across Mexico. No matter how they travel, once they’ve arrived, many of them will walk on their knees into the basilica while others will wash their faces with the water that flows by statues of the Virgin. A short distance away in the large plaza, Indigenous and traditional groups dance to the beat of drums. Everyone is there to commemorate the appearance of the Virgin Mary to Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoztzin—usually known simply as Juan Diego—in 1531. This year, it’s estimated that between 11 and 13 million people made the pilgrimage.

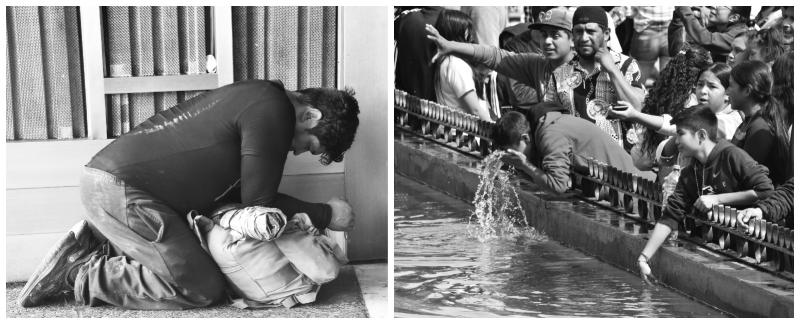

Right: People washing their faces with water that flows past the statues of the Virgin

The Virgin Mary is believed to have appeared to Diego, a Chichimec peasant, four times on Tepeyac hill. The first apparition took place on December 9, when the Virgin appeared as a dark-skinned young woman and spoke to Diego in his language, Nahuatl. She instructed him to tell the local bishop, Juan de Zumárrago, to build a chapel on the site of her appearance, which Diego did. But Bishop Zumárrago didn’t believe Diego’s story and asked for proof. In her final apparition, on December 12, Mary told Diego to climb Tepeyac and collect the flowers he would find there (out of place and out of season). Sure enough, he found the flowers and collected them in his tilma (cloak), then went to see the bishop. When Diego opened his tilma, the flowers tumbled out and there was an image of the Virgin imprinted on its cloth. Zumárrago ordered the chapel to be built. Diego’s tilma now hangs above the altar in a modern basilica at the Villa.

Long before the Virgin’s apparition, a temple dedicated to Tonantzin, an Aztec goddess, stood at the base of Tepeyac. Tonantzin, whose name means “our venerable mother,” was an important figure—a mother goddess associated with agriculture and fertility. It was said that she, too, had appeared to Mexicas atop Tepeyac. So the Catholic chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe was built on top of what had been a pre-Hispanic religious site. Such cultic palimpsests are common in Mexico.

There are those who don’t believe that the Virgin appeared to Diego or that the painting on the tilma was divinely created. And of course there are those who doubt that Tonantzin ever appeared to Mexicas. But the pilgrims who travel to the Villa appear to have few doubts. The Catholic pilgrims go to venerate the Virgin Mary; Indigenous groups go to venerate Tonantzin; and Indigenous Catholics go to venerate both. It makes for an interesting mixture of sights and sounds, especially on the Día de la Virgen de Guadalupe.

The bronze bells tied to dancers’ ankles ring out as they stomp in time to the music. Nearby in the plaza, several people, exhausted from their long journey, are somehow able to sleep.

Members of the Danza de Arrieros de Fe y Tradición (“Dance of the Muleteers of Faith and Tradition”) traveled in trucks from San Miguel Ameyalco, Mexico State, arriving at the Villa on December 10. They danced for about seven hours each day, dressed in traditional campesino clothing and sombreros. Their dance represents the hard life of muleteers who once transported goods between pueblos. “This dance is an expression of our faith,” a man named Jovani Blas told me. “We ask [the Virgin] for health, to care for our family. On this occasion, I came to give thanks to the Virgin”—adding, “It is because I like the dance.”

Across from them, two groups from Puebla state performed the Danza de Pilatos (“Dance of the Pilates”), a dance representing battles between Moors and Catholics that lasts between two and three hours. The dancers wear headdresses that weigh about seven pounds and bronze bells on their legs that weigh another ten. “We dance to honor the Virgin,” said Bernardino Garcia Garcia. “I am a Catholic and I am an Indigenous. For us, Tonantzin and the Virgin are the same. Tonantzin is the Virgin and the Virgin is Tonantzin. There is no conflict: para nada.” Javier Castillo Castillo, a dancer in the other group, pointed out that Indigenous Mexicans who aren’t Catholic typically don’t enter the basilica. “We are Catholic,” he said, “so we enter.”

Victor Garcia Santa Cruz knelt at the entrance to the basilica. He had walked alone from San Antonio Tizostoc, Tlaxcala: seventy miles in two days—eight hours the first day and fifteen the second. “It is an act of faith,” he said. I asked what he was praying for. “I ask her to give me work, I ask for health, to care for my family. I thank her for all her blessings and ask for forgiveness for my sins.”

A small group from Atlixco, Puebla, arrived at the Villa on December 11 after walking eighty miles in three days. “We awoke at 5:00 and walked until midnight,” said Brigida Mexquititla Cuatlayotl. “My legs hurt but it is worth it.” They slept along the road, and when I asked if she had been afraid, she said, “We are not afraid because we come with faith. It is important to have faith to continue.” During the pilgrimage, she carried a banner she had embroidered with an image of the Virgin; it had taken her a year to finish it. “I usually worked every day for three hours,” she said. “It is another way to give thanks, to show our faith and love for her.”

Just inside the entrance to the Villa stood three young women, each carrying on her back a large statue of the Virgin. They and their group had walked all the way from San Miguel Canoa, Puebla, ninety miles from Mexico City. The journey had taken four days. Each day they walked for about fifteen hours, each member of their group carrying the statues for about three hours. “I did it to show the great faith I have in the Virgin,” Beatriz Arce Montes told me. “I come to worship her, to show my love.” They, too, had slept rough along the way. I pointed out that Mexico can be a dangerous place for travelers. “I have no fear,” she said, “because faith is much bigger than fear.”