Americans have insufficient antipathy toward the extraordinarily rich. I hope this isn’t a controversial view. We like them too much. Despite a short-lived blossoming of post-recession anger toward the “one percent,” and the efforts of anti-plutocratic politicians like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, Americans persist in seeing extreme wealth as a virtue—a sign of integrity, intelligence, merit. Those who have it garner respect and deference, even reverence. Being wealthy signifies that you have done something good, achieved something praiseworthy. More than any previous presidential candidate, Donald Trump made his net worth a centerpiece of his campaign, the proof he was worthy of the office. His opponent, in turn, sought to portray him as not quite as wealthy as he claimed: a boastful con man, not a real billionaire. We know how well that worked.

The notion that being a billionaire itself might be disqualifying—a hindrance rather than an advantage when leading the country—never seemed to cross anyone’s mind. But it should have. The conventional wisdom that millionaires and billionaires are “out of touch” contains within it a capacious truth. Very rich people tend to be less empathetic, less altruistic, and more selfish than people of lesser means. Psychological studies confirm this. Their wealth instrumentalizes their relationships to others, even those they love. It isolates them from the vast majority of non-rich people and alienates them from our concerns, our lived experience, our suffering. To put it plainly, extraordinarily wealthy people are not “like us,” and I see no good moral or political reason why we should pretend that they are.

On the contrary, the instinct to forgive and (worse) identify with the very wealthy has extremely bad political effects. It gives us presidents like Donald Trump—and, let’s be frank, candidates like Hillary Clinton. It eases the passage of upward redistribution, normalizes the logic of austerity, and undermines the basis for mass working-class politics. The cruel irony is that it is precisely the working class’s superior capacity to empathize with others and to see ourselves in them—a tendency toward mutual care and concern born of necessity—that makes us so vulnerable to the war the rich have been waging (and winning) against us for ages. The rich, meanwhile, harbor no such illusions. They don’t think we are like them. They hardly think of us at all. While we live our lives—and vote—as if we’re all, already, fundamentally the same, the rich do everything in their power to ensure that we remain fundamentally different. The wolves are wearing wolves’ clothing, but we’re still treating them like sheep.

The opaque means by which the wealthy preserve their luxury at our expense is the subject of Brooke Harrington’s new book Capital without Borders: Wealth Managers and the One Percent. The book addresses a challenging sociological question: Who are the agents engaged in the maintenance of wealth stratification and what are their methods? Harrington’s study points the finger at a little-understood class of professionals known euphemistically as “wealth managers.” Their role in exacerbating the ever-growing chasm of wealth inequality, Harrington believes, has been woefully underappreciated.

Her account of the social, cultural, and financial intricacies of this profession—about two-thirds of the book—is no small feat. Owing to the secrecy and discretion demanded by “ultra-high net worth” individuals, wealth managers are not predisposed to divulging the details of their work. Especially not to curious outsiders with digital recorders. Nor is there a significant material archive to draw from. Wealth management, by design, leaves little in the way of a paper trail.

In overcoming these obstacles, Harrington displays an admirable degree of sociological grit. In 2007, she enrolled in a certification program in Trust and Estate Planning (TEP) herself. Two years later, she graduated with honors. Her immersion afforded her a semi-insider’s perspective. She gained access to proprietary training materials and was welcomed into a professional society of wealth managers. Most importantly, she used her certification to gain the trust of her interview participants, whose candid (albeit anonymous) responses are the basis for the book.

Harrington serves as a sort of Virgil for the reader. Only our Virgil has spent two years—in Switzerland!—training in the implementation of the sordid degradations on display. I myself experienced a mild vertigo, a mixture of titillation and disgust, at the book’s glimpses of unfathomable luxury and the ornate means undertaken to preserve it. This proximity to power and intimacy with its inner workings is one of the draws of the profession. Harrington’s respondents tell stories of globe-trotting daytrips on private jets and late-night drinks with heads of industry and heads of state. Wealth managers become their clients’ most intimate confidants, entrusted with a family’s darkest secrets. As Eleanor, an American practitioner, put it, “It’s like being a voyeur…the client has to undress in front of you.”

What do wealth managers do exactly? In short, they engage in a form of preemptive warfare against the forces of wealth depletion—whether that means tax authorities, creditors, courts, regulators, or even spendthrift relatives. Practitioners erect a globe-straddling architecture to house their client’s wealth that is simultaneously dynamic, impenetrable, and opaque. And thanks to the financialization of our economy, especially since the 1980s, wealth is unprecedentedly fungible and mobile. “Keeping assets circulating among structures and across jurisdictions,” Harrington writes, “allows them to move through the regulatory apparatus of nation-states in a nearly frictionless manner.”

The building blocks of these asset-holding structures are trusts, foundations, and corporations. Perhaps the most notorious of these is the trust—as in “trust fund”—a fiduciary arrangement in which a portion of private wealth is sequestered from an estate, allowing the beneficiary (often an heir) to enjoy the benefits of ownership without incurring its duties and liabilities. The mortar, however, is the “offshore financial center” (OFC). The textbook on which the TEP certification is based opens with twenty-eight pages dedicated to OFCs. States like the Cayman Islands, Cook Islands, British Virgin Islands, Jersey (not that Jersey), and Mauritius have organized their legal systems to accommodate the priorities of the global elite and their fiduciaries. These locales, writes Harrington, are “zones of freedom from regulation and accountability,” characterized by little to no taxes and hands-off (but politically stable) governance.

Wealth managers use “regulatory arbitrage” to “liberate” their clients from the rule of law. That is their job. To unencumber the wealthy from the legal and civic obligations that apply to the rest of us: the obligation to pay our taxes, to pay our debts, to pay our civil liabilities. As Nicolas Shaxson, an expert on offshore finance has observed, the project of global wealth management is to offer “escape routes” for wealthy elites to avoid “the duties that come with living in and obtaining benefits from society.” Taken together, these strategies shift the fiscal burdens of society downward, “imposing a surcharge on those who are unable to afford” them. In the United States, that surcharge could be as much as 15 percent in additional taxes to cover hundreds of billions underpaid by the wealthiest individuals and companies.*

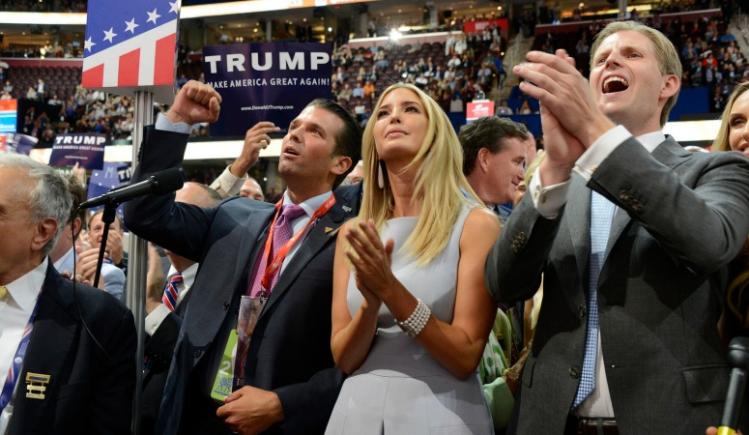

In the final third of Capital without Borders, Harrington helps dispel two of the most pernicious myths underlying America’s overly tolerant attitude toward the extremely rich: first, that they deserve to be so, and second, that the rest of us might one day be extremely rich too. The first falls when we understand that the vast majority of these high-net-worth individuals—including our president and his children—have benefited from dynastic wealth. As legal scholar Lawrence Friedman has said, “An upper class is a class that inherits. A lower class is a class that inherits nothing.” In the next three decades, it’s estimated that between $10 and $41 trillion in private wealth will be inherited in the United States. Practically all of it will descend to a tiny fraction of the population. Eighty percent of us will inherit nothing at all.

The second myth is dispelled when we realize that, for much the same reason, the prospects that the non-rich will accumulate great or even significant wealth in their lifetimes are miniscule. This is Thomas Piketty’s central insight, made famous by his blockbuster book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. When the rate of return on capital (r) exceeds the rate of economic growth (g)—as has been the case for most of human history—wealth originating in the past inevitably grows faster than wealth stemming from work. The wealth you create from your labor (unless you’re Taylor Swift or LeBron James) simply cannot compete with wealth derived from inheritance. We’re screwed from the start.

The relatively low inequality we associate with the middle twentieth century is an exception to this rule, born of a brief period in which g exceeded r—which was as much the result of wartime devastation and post-war recovery as redistribution (though higher taxes and regulation didn’t hurt). We have since returned to the norm. In the latter half of the twentieth century, growth in the United States and Europe stagnated while the rate of return on capital surged. States—captured by the super-rich and eager to attract mobile capital from the global market—have done less and less to counteract its effects. As a result, intergenerational transfers of wealth have acquired a “self-perpetuating momentum” that increases inequality generation after generation.

Wealth managers, Harrington suggests, have enabled and exacerbated these conditions. By all but obviating inheritance taxes—as one practitioner said, “the estate tax is a voluntary tax in our country; you only pay it if you don’t plan”—avoiding the pitfalls of liability and risk, and sheltering dynastic wealth from taxes on capital gains, wealth managers have set in motion a “perpetual money-making machine.” They ensure that the benefits of accumulated wealth accrue to a single bloodline and sabotage the state’s means of generating upward mobility. Wealth managers are foot soldiers in the preservation of class hierarchy.

The severity of this situation, the sheer Dickensian absurdity of it, is perhaps our best hope that what Harrington calls the “moral valence attached to wealth” might shift back in a more healthy direction—away from the blinkered admiration that helped bring us President Trump and toward a more clear-eyed suspicion of the rich and their enablers. It was not so long ago, in perhaps analogous times, that an American president said, “The transmission from generation to generation of vast fortunes by will, inheritance, or gift is not consistent with the ideals and sentiments of the American people.” It would be an unmitigated good for the vast majority of us if we once again concluded, as FDR did, that such “great accumulations of wealth” perpetuate an “undesirable concentration of control in relatively few individuals over the enjoyment and welfare of many, many others.”

At the very least, we might start by resenting the extremely rich for what they are doing to us. After all, we expect the wolf to eat the lamb. But we don’t expect the lamb to praise him while he does it.

*This review reproduced a mistaken calculation from Capital without Borders. It has been updated.